- Author: Royce Larsen

- Editor: Sophie Kolding

Most of the oak woodlands in California are privately owned. The major use of Oak Woodlands is for grazing, primarily for beef cattle. The ranching industry plays an important role in maintaining a sustainable, culturally meaningful, and ecologically rich landscape (Huntsinger and Hopkinson, 1996) in our oak woodlands. Of the many challenges facing ranchers, droughts can be severe.

The great drought of 1862–1865 wreaked havoc on the state and the cattle industry (Burcham, 1957). Since that time we have had severe droughts about 8 times (George et. al. 2010). Even with less severe droughts, cattlemen have a stressful time dealing with changes in forage production. With less forage production, cattlemen either have to reduce herd size, move cattle to other states or locations, or provide extra feed at a great expense. If cattle are sold, it may take several years to build the herd back.

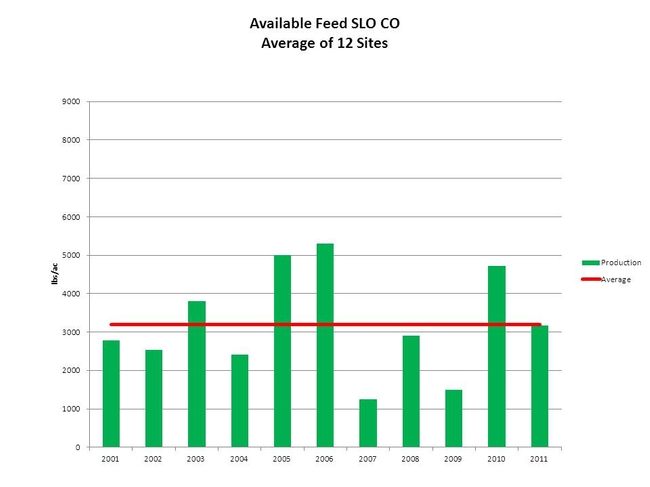

Not all droughts are equal. Droughts tend to be more common in the rain shadow along the Coast Range adjacent to the west edge of the San Joaquin Valley (George et. al. 2010). Even though drought conditions create havoc with management of ranches, ranchers also have to deal with wetter than normal years. There is no such thing as an average year, which makes management decisions very difficult. Forage production and quality can vary greatly from year to year, and is strongly influenced by the timing and amount of rainfall (George et. al. 2001). For example, forage production in San Luis Obispo County over the last 11 years has varied by as much as 4000 lbs/ac (Figure 1). Rainfall amount and timing played a significant role in this variation, which varied by 18 inches of annual precipitation.

Figure 1: Peak Forage Production in San Luis Obispo County from 2001 – 2011.

An average of 12 sites across the county.

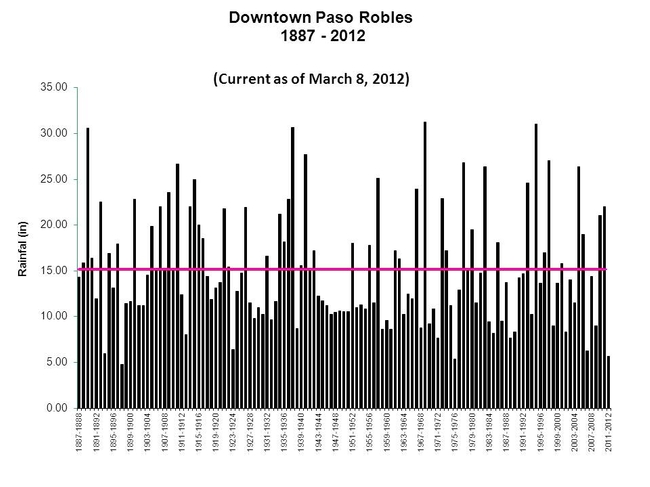

It is just a fact of life that rainfall amount and timing varies. For example, the lowest rainfall recorded in downtown Paso Robles was 4.8 inches in 1898 (Figure 2). The highest recorded was 31.3 inches in 1969, the year of the big flood. It is important to notice that 6 out 10 years are below average (Figure 2). This means that the four years that are above average are usually wet years, which often produces extra forage. For more practical purposes, the years that are below the average determine what and how much forage can be produced on a ranch, which determines the number of cattle that can be grazed on a sustainable basis. It is very important to the ecological health of the oak woodlands / grasslands to maintain proper stocking rates to achieve the desired grazing level. Maintaining the proper amount of residual dry matter (RDM) has become the standard to determine grazing use on oak woodlands and annual grasslands. Properly managed RDM provides protection from soil erosion and nutrient losses, and also plays an important role determining the following year’s production and composition of species (Bartolome et. al. 2006). To accomplish this requires constant change in management by ranchers. I applaud those ranchers who work so hard to accomplish this.

Figure 2: Rainfall records at the down town Paso Robles. Data is based on water

year July 1 – June 30. Average precipitation is 15 in/yr.

Below are images taken of the peak forage production for San Luis Obispo County:

Spring 2006 normal, wet conditions

Soda Lake Site Cambria Site

Spring 2007 drought conditions

Soda Lake Site Cambria Site

References

Burcham, L.T. 1957. California range land: An historico-ecological study of the range resource of California. Division of Forestry, Department of Natural Resources, State of California, Sacramento, California, USA.

Bartolome, J.W., W.E. Frost, N.K. McDougald, and M. Connor. 2006. California guidelines for residual dry matter (RDM) management on the coastal and foothill annual rangelands. Oakland, CA USA: Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California, Publication 8092.

Huntsinger, L. and P. Hopkinson. 1996. Viewpoint: Sustaining rangeland landscapes: a social and ecological process. Journal of Range Management 49(2):167-173.

George, M.R., R.E. Larsen, N.M. McDougald, C.E. Vaughn, D.K. Flavell, D.M. Dudley, W.E. Frost, K.D. Striby, and L.C. Forero. 2010. Determining Drought on California’s Mediterranean-Type Rangelands: The Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program. Rangelands 32(3):16-20.

- Author: Sophie Kolding

Author: Greg Giusti

Throughout northern coastal California, a great deal of information regarding water quality and fish habitat is being amassed that potentially could change how people view and utilize stream corridors. However, it is widely recognized among the scientific community that stream corridors are an important habitat component for a host of vertebrate and invertebrate species other than fish. Unfortunately, the current fish-centric approach to riparian protection and restoration has often resulted in a narrow discussion of stream corridor management that excludes non-fish species. For example, information detailing the use of oak woodland stream corridors by migratory songbirds in California’s oak woodlands is sorely lacking, limiting the ability of landowners and resource managers to make informed decisions regarding land use practices and policies and their effects on birds. It is important that we consider these other species when managing and restoring riparian areas, as their requirements may be different than those of the fish.

Spring 2012 marks the 20th consecutive year of a bird monitoring study on Parson’s Creek, an ephemeral (seasonal) tributary of the Russian River that traverses the UC Hopland Research and Extension Center (HREC). The goal of this ongoing project is to document resident and migratory bird use of stream corridors in mixed oak woodlands.

the bark, limbs, twigs and leaves of trees. The species is a cavity nester.

Study Site and Sampling Methods

Parson’s Creek, like most creeks in the North Coast, has been subject to many land use impacts over the past 100 years, including livestock grazing, gravel extraction, channelization, and road crossings with associated aggravated erosion. To offset many of these impacts, HREC instituted a series of restoration activities in the early 1990’s to serve as demonstrations to landowners who are interested in stream restoration. Since then, recovery of native vegetation in some sections of Parson’s Creek has been dramatic. In areas that have excluded both sheep and deer, alder and willow have regenerated and are now providing extensive vegetative cover. Other sections were left unprotected and remain denuded, demonstrating how the restored sites used to look. Consequently, vegetative cover is not uniformly distributed throughout the stream reach. Other over-story species that exist across the study area include blue oak, Oregon white oak (also known as Garry oak), and valley oak.

Twelve monitoring points are established along the main creek channel at HREC. Birds are surveyed using a standard sampling protocol commonly referred to as the “point count method”. This method is widely used to survey birds in the field and involves an observer recording birds from a single point for a set length of time.

Each monitoring point is surveyed 3 times a year during the morning. Two 20-minute counts are conducted each spring between mid-May and early June to coincide with the arrival of migratory songbirds. In addition, one 20-minute count is conducted each fall in mid-October, after the departure of neo-tropical migrants to wintering grounds in the tropics. Birds were identified using visual and auditory cues. Only those birds active (perching, foraging, singing, etc.) within the riparian corridor were tallied. Birds flying high above or passing through the stream zone were not counted.

is regularly observed in the woody portions of Parson’s Creek.

Findings

Thousands of bird observations have been recorded. The total number of observations per year ranged from a high of 254 (1993) to a low of 173 (1999). The average number of recorded observations over time is 198 detections per year. The unusually high number of recorded observations in 1993 is most likely an aberration of sampling, not a trend in bird presence. Following the first year, the observers became more conservative and standardized in their data collection.

The large number of bird detections yielded an impressive number of species—81 species, representing 24 taxonomic families and 9 orders. Both resident and migratory species were detected in the oak woodland stream corridor. Species most commonly observed and the corresponding number of detections during the study period is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Most commonly observed species in the Parson's Creek riparian corridor, HREC.

Ten Most Commonly Ten Most Commonly Observed

Observed Species Neo-Tropical Migratory Species

|

Oak Titmouse (125) Acorn Woodpecker (103) California Towhee (94) Western Scrub-Jay (78) European Starling (66) Black Phoebe (62) House Finch (59) Brewer's Blackbird (54) Nuttall's Woodpecker (52) Anna's Hummingbird (46) |

Bullock's Oriole (54) Orange-crowned Warbler (49) Violet-green Swallow (43) Ash-throated Flycatcher (37) Pacific-slope Flycatcher (33) Western Tanager (27) Lazuli Bunting (26) Warbling Vireo (25) Western Kingbird (24) Black-headed Brosbeak (22) |

Throughout the study period, an average of 29 species (ranging from 27 to 33) have been detected during the Fall. These species are primarily resident birds that utilize the stream corridor throughout the year. Spring counts averaged 43 species (ranging from 38 to 48). The difference in the average total number of species reflects the seasonal influx of neotropical migratory songbirds that arrive in California’s oak woodlands for the breeding season.

Some species may also be selectively utilizing only portions of the riparian corridor that exhibit special habitat features. For instance, one species in particular, the Black-throated Gray Warbler (Dendroica nigrescens), is consistently found only in those portions of the riparian area where the vegetation canopy is densest. This pattern of occurrence has remained consistent during the entire study period, and suggests that this species may have relatively narrow habitat requirements when compared to other neotropical migrants exploiting the stream corridor.

vegetation. The bird lays its eggs among the barren rocks. The cryptically

colored eggs are virtually invisible. This is one of the few species that

is not dependent on vegetation in oak woodland settings.

Conclusion

There is very little long-term information detailing the use of oak woodland stream corridors by migratory and resident birds in California’s oak woodlands. Our long-term data set demonstrates that migratory songbirds readily utilize the riparian zone, particularly during the spring breeding season. We also observed that some species are more abundant in sections of the creek where more mature vegetation is present.

We plan to continue to monitor the avian assemblage found within this stream corridor. It is our hope that this project, along with the efforts of others, will generate important, long-term, baseline information that will aid in the sustainable management of California’s riparian hardwood communities.