- Author: Ben Faber

From the Avocado Hass Board:

Avocado World Market Projection Up to 2030

A global study of the complex factors influencing the supply and demand of avocados around the world reveals challenges and opportunities on the horizon.

At the current pace, there will likely be a surplus by 2030 so research has been updated to evaluate ways for the industry to act now including stepping up demand creation to stay competitive.

Eric Imbert, a lead researcher from CIRAD, French Agricultural Research Center for International Development, reviews the quickly evolving trends and his three key pieces of advice for the global industry.

ERIC IMBERT

CIRAD: French Agricultural Research Center for International Development

- Author: Ben Faber

Here's an example of the kind of information that can be both exciting and disappointing - forecasts of the future of the citrus and avocado industries and many other fruit and nut crops. The latest forecasts are available form the USDA - Economic Research Service:

https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/92731/fts-368.pdf?v=7239.3

Wednesday, April 24, 2019

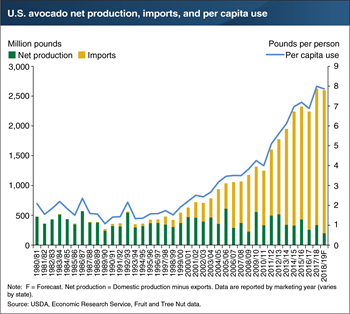

Imports play a significant role in meeting the U.S. demand for avocados. Since the mid-1990s, imports of avocados have grown sharply as per capita consumption has grown, representing 87 percent of domestic use in the 2017/18 marketing year. USDA forecasts that imports will make up an even larger share of supply in 2018/19, mainly because California's crop is expected to be smaller than in recent years. Contributing factors to this reduced crop include record-breaking heatwaves in July 2018 followed by record-breaking wildfires, as well as recent rains and cold weather, and the general alternate-year-bearing nature of avocado trees (whereby a large crop one year is followed by a smaller crop the next year). Because over 80 percent of all U.S.-produced avocados each year are from California, California's low harvest in 2018/19 should boost U.S. demand for imported avocados (especially from Mexico) even higher than it has been in recent years. If USDA's forecast is realized, imports in 2018/19 will represent 93 percent of the domestic avocado supply. This chart appears in the ERS Fruit and Tree Nuts Outlook newsletter, released in March 2019.

Fruit & Tree Nuts

Provides current intelligence and forecasts the effects of changing conditions in the U.S. fruit and tree nuts sector. Topics include production, consumption, shipments, trade, prices received, and more.

https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/92731/fts-368.pdf?v=7239.3

Can the past foretell the future?

- Author: Ben Faber

Avocado is a tree that has a good ability to respond to fire damage, if it is not too extensive. However, often a tree will recover only to collapse later on in the year or years because of the damage. So a tree may appear to do well and then suddenly collapse. In an orchard setting, fire damage can kill one tree completely, whereas the one just beside it recovers completely. This poses a major problem with irrigation management. How to irrigate the slowly regenerating tree that gradually needs more water, less frequently, next to trees that are recovering at a different rate or not at all. This becomes a management nightmare. Often the result of the difficulty of water management, the remaining trees develop root rot and they eventually die from that and not the original fire damage.

There is a general rule of thumb I have learned and used – when more than 50% of the trees have succumbed, it is best to replace the whole orchard. This is due to the issues of irrigation management and the loss of return from the unused portion of the grove.

So, from a pure economic management aspect, where there is any fire damage, that area should be considered a loss. If you look at your aerial survey and just measure the areas that show fire damage and take that as a proportion of the total planted area, you should be able to assess the extent of the damage incurred in the fire. So measuring the brown areas relative to green should give you a good assessment of the damage incurred in the fire.

It may be possible to nurse back individual trees with a lot of attention and if it's a small enough area, go ahead. But on commercial scale of acres, it often doesn't pay from a management point of view to nurse the orchard to an economic production level.

Fire Information:

http://ceventura.ucanr.edu/Agricultural_Threats/Fire_Information/

- Author: Ben Faber

The latest cost of production study done on oranges came out recently.

It applies to the San Joaquin parts of the Valley for sure, but many of the assumptions are true for evergreen tree crops in general. The cost of weed control, or fertilizing are not going to be different. Pest and disease control are going to be very different if you are a navel orange grower in Bakersfield or a cherimoya grower in Santa Barbara. The key to these studies are the different issues/categories a grower should be addressing and the studies provide a framework for that study. Also it gives general costs for different inputs, such as urea and glyphosate to make a comparison to what you might be paying

- Author: Ben Faber

Assessing water quality for Southern California agriculture typically revolves around the total salinity of the water, its total dissolved solids (TDS), and the toxic ions boron, sodium and chloride. Salts are necessary to plants, because it is in the form of diluted salts that all nutrients are taken up by plants- the macro and micronutrients plants extract from the soil. High salinity leads to water imbalance problems much as if the plant were not getting adequate water. A toxicity problem is different from a salinity problem, in that toxicity is a result of damage within the plant rather than a water shortage. Toxicity results when the plant takes up the toxic ions and accumulates the ions in the leaf. The leaf damage that occurs from both toxicity and salinity are similar in that it causes tissue death known commonly as "tip burn." The damage that occurs depends on the concentration of the ions in the soil water around the roots, the crop sensitivity and crop water use, and the length of time the crop experiences the ions. In many cases, yield reduction occurs. Because crops can not excrete salts the way humans do, salts gradually accumulate in a plant. As a result plants need a higher water quality than humans do.

Much study in many countries has gone into evaluating water for crop use. Some of these studies have been on the effects of salts on soil characteristics. Generally, as sodium concentration increases, a soil will lose its aggregation, eventually leading to poor water infiltration. Many more salinity and toxicity studies have been done on plants themselves. Not all crops are equally tolerant of salinity and toxicities, and in general most plants respond to salinity and toxicities in a similar fashion. If a plant is intolerant of salinity, it will be intolerant of chloride, sodium and boron. Most annual crops are less sensitive to salts than tree crops and woody perennials, although symptoms can appear on any crop if concentrations are high enough. The reason for greater sensitivity for perennial crops is that the tree is sitting in the ground absorbing salts for a longer period than the lettuce plant that is harvested 3 months after planting. Furthermore, deciduous trees like walnut shed their leaves each winter, so they can handle salinity better than evergreens like citrus and avocado.

To manage salinity and toxicities, water management is the key. Depending on water quality, an excess of water will be applied to the soil to leach the previously applied salts away from the root zone. The poorer the water quality, the more excess water is applied.

Selecting a less sensitive crop is also an alternative when dealing with poor water quality. Some barley varieties can handle salinity similar to ocean water. Barley nets a grower $400 an acre, avocados $9,000 and $25,000 if the market is right for strawberries. Avocados are salt sensitive, so are strawberries and lemons and cherimoyas and star fruit and blueberries and raspberries and mandarins and nursery crops. We grow these because with our climate, very few other places can grow them and they return enough money for a grower to stay in business in an area where land, water and labor are expensive. We really don't have much in "alternative crops" to grow here.