- Author: Shimat Villanassery Joseph

Cabbage maggot (Delia radicum) is a serious insect pest of Brassica crops such as broccoli and cauliflower in the Central Coast of California. These crops are grown throughout the year; as a result cabbage maggot problems persist year long.Cabbage maggot eggs are primarily laid in the soil around the crown area of the plant. A single female fly can lay 300 eggs under laboratory conditions. The eggs hatch within 2-3 days and the maggots feed on the taproot for up to three weeks and can destroy the root system of the plant. The maggots pupate in the soil surrounding the root system and emerge into flies within 2-4 weeks. Severe cabbage maggot feeding injury to the roots cause yellowing, stunting even plant death.

Control of cabbage maggot on Brassica crops primarily involves the use of soil applied organophosphate insecticides such as chlorpyrifos and diazinon. However, the persistent use of organophosphate insecticides has resulted in high concentrations of the insecticide residues in the water bodies posing risks to non-target organisms and public health through contaminated water. Currently, use of organophosphate insecticides is strictly regulated by California Department of Pesticide Regulation. There is therefore an urgent need to determine the efficacy of alternate insecticides for cabbage maggot control.

The efficacy of 29 insecticides was determined against cabbage maggot through a laboratory bioassay by exposing field collected maggots to insecticide treated soil immediately after application. Three parameters were used to evaluate efficacy (1) proportion of maggots on the soil surface after 24 h, (2) proportion of change in weight of turnip bait, and (3) dead maggots after 72 h. Based on the assays, 11 insecticides performed better and they were Mustang, Torac, Danitol, Belay, Capture, Warrior II, Lorsban, Mocap, Durivo, Pyganic and Vydate in the order of highest to lowest efficacy. Eight insecticides were selected based on superior efficacy to determine the length of residual activity on cabbage maggot larvae. The persistence of insecticide activity was greater with Capture, Torac and Belay than with other insecticides tested.

The mode of exposure of insecticides in this study was entirely by contact (through skin) and other modes of exposure such as ingestion (through mouth) or through respiratory holes (spiracles) were not investigated. Some of the insecticides tested in the study were insect growth regulators (IGRs) (Dimilin, Rimon, Trigard, and Aza-direct), which normally interfere with the growth and development of the insect and they showed a low efficacy against cabbage maggot larvae. Entrust (spinosad) showed a moderate efficacy possibly because the primary mode of exposure to Entrust is by ingestion. The diamide insecticides (Beleaf, Coragen and Verimark) have systemic activity as they move within the plant and likely away from the site of application. It is possible that the soil applied diamide insecticides are absorbed by the roots and translocated to the above ground plant parts with little effect on the feeding larvae in the tap roots.

This study was conducted under controlled conditions in the laboratory and the results may not be entirely consistent in field conditions. The Brassica fields in the California's Central Coast are profusely sprinkler irrigated up to three weeks after sowing to ensure uniform germination and proper establishment of plants. It is likely that applied insecticides are partially or completely leached out of the root zone area without providing anticipated maggot control. In this study, insecticides were drenched into the cup and none of the applied insecticide solution leached out. Therefore, it is likely that the insecticides were more effective in the laboratory assay than they would be in the field. Certain insecticides such as pyrethroids tend to bind to the soil organic matter. The organic matter in the California's Central Coast soils can be up to 4%, which could reduce the availability of soil applied pyrethroid insecticide to the root zone where cabbage maggot larvae typically colonize. In situations with poor insecticide spray coverage, invading cabbage maggot larvae are possibly exposed to no or sub-lethal doses of the soil applied insecticide and may be able to penetrate the soil and infest the roots. The air temperature in the field at the time of insecticide application may influence the efficacy of the applied insecticide. The efficacy of pyganic decreased as the temperature increased against onion maggot. This suggests that application of pyrethroid insecticides should be avoided during warmer periods of day.

Other field conditions that influence efficacy of insecticides are cabbage maggot incidence and frequency of invading cabbage maggot flies on Brassica crop in the Central Coast of California. The earliest peak of cabbage maggot infestation occur a month after sowing broccoli seeds and infestations can be continuous until harvest. Also, insecticides applied at sowing as a banded spray on the seed lines did not provide adequate cabbage maggot control based on the insecticide efficacy trials conducted in commercial broccoli fields. These findings suggest that delaying the insecticide application by 2-3 weeks after sowing is more likely to maximize maggot control. Because the cabbage maggot infestation can last several weeks, insecticides with extended persistence of efficacy would increase the value for cabbage maggot control. Overall, results show that Capture, Torac and Belay which performed effectively against cabbage maggot for a month after application. This indicates that insecticides used before the first peak of infestation may protect the younger stages of the Brassica plants allowing them to establish and tolerate milder cabbage maggot infestations thereafter.

In conclusion, 11 insecticides with high efficacy were identified for future investigation. Future studies will focus on determining the effects of application timing and delivery methods compatible with cabbage maggot incidence in both directly sown and transplanted Brassica crops in the Central Coast of California.

If you are interested in reading the details of this study, please click the link below to access the published article.

- Author: Shimat V. Joseph

ATTN: Recently, bagrada bug adults were found on Chinese or napa cabbage in Santa Cruz County.

Although this bug feeds on a wide range of hosts, we are more concerned because the bug prefers cruciferous hosts (Family: Brassicaceae) including broccoli and cauliflower, which are grown as rotation crops in the Salinas Valley. It is believed that other major crops especially lettuce and spinach are NOT a suitable host for bagrada bug. At the same time, bagrada bug can survive on cruciferous weeds such as mustard species (Brassica sp), wild radish, London rocket, short pod mustard and shepherd’s purse, as well as the insectary crop sweet asylum. Mustard weeds species are very common in the Salinas Valley along ditches, roadsides and even along the edges of agricultural fields. Other species of mustards such as white mustard (Sinapsis alba) and Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) are grown as cover crops. It is clear that given the abundance of mustard family weeds and crops, there is a readily available source of habitat for this insect in the Salinas Valley.

Bagrada bug adult is often confused with harlequin bug. Adult of harlequin bug is orange with black and white marks, whereas bagrada bug adult is black with orange and white marks; and adult harlequin bug is about 3 times larger than bagrada bug (Fig. 2). Eggs of harlequin bug are white with horizontal, black strips, whereas bagrada bug has no strips but has a “dirty” white appearance.

|

It is believed that bagrada bug overwinters as adult in the cracks and crevices in soil or on plants. Generally, female bug is larger in size than male. Eggs are laid on the underside of leaves, cracks and crevices in soil or on hairy stems. There are five nymphal stages for bagrada bug. Typically, bagrada bug is found in aggregation with various nymphal stages and adult rather than individuals (Fig. 3). Because Salinas Valley has relatively mild temperature through year, it is expected that the development of bagrada bug would be prolonged compared with its populations in the warmer regions where it has been established. This also indicates that, if the bug is established, the number of generations of bagrada bug would be fewer in the Valley than in the warmer locations such as southern California or in the desert regions. Normally, its population size is small during early spring to mid-summer but eventually increases in size during later summer or fall.

At this point, preventing the dispersal of bagrada bug to the Salinas Valley is the key strategy. Growers often move plant materials including transplants to the Valley for production from the regions where the bug has been established. Special care should be given to inspect the plant materials while moving them. Monitoring for bagrada bug during mid-day hours might increase the probability of finding them as the bugs typically hide and stay in the cracks and crevices or on the underside of leaves when the temperature is on the cooler side. Cruciferous weeds in the drains, river bottoms, edges of the field or near residential area increase the risk of establishment. Based on the insecticide efficacy studies conducted in University of Arizona, pyrethroids and neonicotinoids are effective in reducing bagrada bug infestation and injury. For organic growers, none of the products are efficacious but pyrethrin and azidirachtin are suggested.

If you detect bagrada bug in Monterey, Santa Cruz and San Benito Counties, please do not hesitate to contact me at svjoseph@ucdavis.edu or (831) 759-7359.

For more reading, please visit the links:

http://cisr.ucr.edu/bagrada_bug.html

http://www.plantmanagementnetwork.org/pub/php/brief/2010/bagrada/

- Author: Steven T. Koike

White mold disease, caused by the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, is causing damage to a number of vegetable crops in California and Arizona during the late 2010 and early 2011 months. On the coast of California, white mold is being found on crucifer crops such as broccoli and cauliflower. In the desert regions white mold is causing damage on broccoli, cauliflower, celery, lettuce, and other vegetables (for lettuce this disease is commonly called lettuce drop). White mold incidence on these crops appears to be greater than normally observed. See photos 1 through 6 below.

The first symptoms on most vegetable crop hosts are small, irregularly shaped, water-soaked areas on stems, leaves, pods, or flower heads. These infections quickly develop into soft, watery, pale brown to gray rots. Rotted areas can expand rapidly and affect a large portion of the plant. Diseased tissues eventually are covered with white mycelium, white mycelial mounds that are immature sclerotia, and finally mature, hard, black sclerotia. Mature sclerotia usually form after tissues are rotting and breaking down. Plants with infections on the main stems can completely collapse and fall over.

The black sclerotium is the survival stage of the fungus and can measure from ¼ to ½ inch long. Sclerotia are found in the soil and can directly infect plants if stems are in close proximity. However, these winter cases of white mold are due to ascospore infections. If sufficient soil moisture is present, shallowly buried sclerotia germinate and form small, tan mushroom-like structures called apothecia (photos 7 and 8). Ascospores (photos 8 and 9) are released from apothecia and carried by winds to the host plant. These ascospores are responsible for these winter infections and result in disease of the above-ground parts of plants. The relatively cool, moist weather found in most regions has allowed for the production of apothecia production and ascospore releases.

For ascospores to start colonizing plant tissues, nutrients and plant fluids from damaged tissues are usually needed. This is why white mold is very severe if ascospores land on compromised tissues such as lettuce leaves with tip burn, leaves and heads damaged by frost or other factors, stems with open wounds or exposed leaf traces (vascular tissue in the stem that is left exposed when a lower leaf falls off), and senescent leaves and stems.

Controlling white mold under these winter weather conditions is difficult. Protective fungicides provide some assistance and can be used effectively in lettuce. However, such fungicides need to be applied prior to ascospore flights and usually will require multiple sprays. Fungicides may not be warranted for crucifer crops.

Steve Koike thanks Jeff Rollins and Karen Chamusco for assistance with photographs for this article.

Photo 1: White mold (lettuce drop) on romaine lettuce.

Photo 2: White mold (lettuce drop) on romaine lettuce, showing white mycelium and two black sclerotia.

Photo 3: White mold on broccoli stems.

Photo 4: White mold on broccoli stem, showing white mycelium and one black sclerotium (center).

Photo 5: White mold on cauliflower head, showing white mycelium.

Photo 6:White mold on celery, showing numerous black sclerotia.

Photo 7: One sclerotium and several apothecia (spore producing structures) of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum.

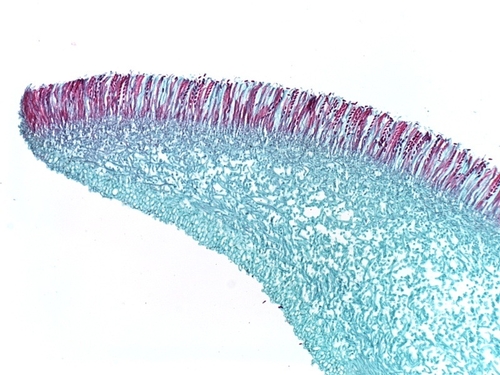

Photo 8: Microscopic view of the spore-producing apothecium of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Note the lined-up ascospores (red) ready to be released. Photo used by permission (K. Chamusco).

Photo 9: Microscopic view of ascospores lined-up in a tube (called an ascus) and ready to be released. Photo used by permission (J. Rollins).

- Author: Steven T. Koike

Downy mildew of lettuce, caused by Bremia lactucae, is the very common foliar disease that results in the familiar yellow to brown leaf lesions and accompanying white sporulation on the lesions. However, the systemic phase of lettuce downy mildew may be less familiar to growers and pest control advisors. In the spring of 2009, systemic downy mildew was very common in coastal California. Currently in 2010, systemic downy mildew is not as serious but is still being observed in some coastal plantings.

Symptoms of systemic downy mildew may be seen on both lettuce leaves and the central, internal core of the lettuce plant. For leaf symptoms, examine the plant for large, elongated regions of the leaf that are discolored and turning dark green to brown. Such regions often develop along the midrib of the leaf and extend into the flat, outer leaf panels (photos 1, 2). White sporulation is often not present on these infected areas until late in disease development. Note that for many systemically infected lettuce plants, these leaf symptoms are absent and the only evident symptoms are in the internal core.

To check for systemic infections in the plant core, cut open and examine the central part of the plant; these tissues will show a dark brown to black streaking and discoloration (photos 3, 4). In some cases, systemically infected plants may be slightly stunted or late in maturing. Exercise caution, however, before concluding that internal core discoloration is due only to systemic downy mildew. Other important lettuce problems (Verticillium wilt, Fusarium wilt, ammonium toxicity) can cause similar internal discolorations.

Confirmation of systemic downy mildew requires laboratory testing. Affected tissues can treated with biological stains and then examined using a microscope. Such procedures can show the presence of the characteristically thick mycelium that lacks cell cross walls (photo 5). In addition, incubating pieces of affected lettuce tissue can result in sporulation of the pathogen (photo 6, showing systemic downy mildew of cauliflower), again enabling confirmation of systemic downy mildew.

Systemic downy mildew of lettuce has not been studied extensively, so researchers do not know exactly what triggers this less common phase of the disease. Some suggest that early infection of young plants may allow the pathogen to infect the inner foliage of lettuce, resulting in pathogen access to the plant growing point. Field personnel also report that some lettuce cultivars are more severely affected than others.

| Photo 1: Brown discoloration due to systemic downy mildew infection in a lettuce leaf |

| Photo 2: Brown discoloration due to systemic downy mildew infection in a lettuce leaf. |

| Photo 3: Internal discoloration of lettuce core due to systemic downy mildew infection |

| Photo 4: Internal discoloration of lettuce core due to systemic downy mildew infection. |

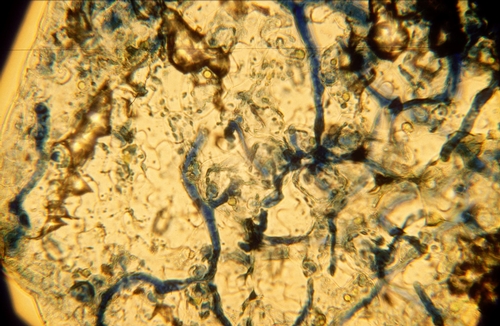

| Photo 5: Blue-stained mycelium of downy mildew that has systemically infected lettuce tissues. |

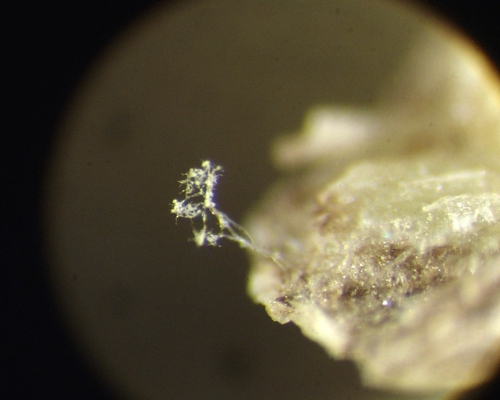

| Photo 6: Sporulating downy mildew from a systemically infected piece of cauliflower stem. |