- Author: Brenda Dawson

The talk, along with introductions, a Q&A session and light refreshments, will be 4-6 p.m. at the Rominger West Winery, 4602 Second St. in Davis. Tickets are $10, and reservations are available online at

http://ucanr.org/slowmoney.

Slow Money is a national network dedicated to investing in local food and agricultural enterprises, which has a Northern California chapter.

“We often hear about ‘voting with your dollar’ when it comes to supporting small-scale farmers and local food,” said Shermain Hardesty, director of the UC Small Farm Program and Cooperative Extension economist with UC Davis. “Shopping at a farmers market or becoming a CSA member are ways to support small-scale farms as a consumer — but Slow Money can be a way to invest in them.”

One local venture that has sought funding through Slow Money is the Capay Valley Farm Shop, a collaborative of 30 farms and ranches who together offer a CSA to institutions and corporations.

“Through Slow Money, we’re reaching investors who share our values, who believe that community food systems are a great investment for the health of communities and for the planet,” said Thomas Nelson, president of Capay Valley Farm Shop.

After presenting at a Slow Money showcase this summer, the Capay Valley Farm Shop is currently working with a group of interested investors through the local chapter.

Another agricultural venture — Soul Food Farm in Vacaville — has received approximately $40,000 in loans from Slow Money investors, according to the group’s website.

“This model is another way that entrepreneurs in sustainable agriculture and community food systems can seek funding — especially when conventional sources such as traditional venture capitalists, the Farm Credit System or commercial banks may not be an option,” Hardesty said.

Hardesty, along with Gail Feenstra of the UC Davis Agricultural Sustainability Institute, is currently studying values-based food systems, where relationships between growers, funders, distributors, consumers and others are based on shared values. The project is working to identify bottlenecks in the development of these values-based food supply chains, with an eye toward enhancing the prosperity of smaller producers through networks that support environmental and social sustainability.

The research is part of a USDA-funded, multi-state project, along with researchers at Colorado State University and Portland State University.

The event is sponsored by the Davis Food Co-op, Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op and the Giannini Foundation.

More details and ticket reservations for the Slow Money event are available at http://ucanr.org/slowmoney.

- Author: Brenda Dawson

“We really all wanted to be farmers, not truckers,” said farmer Dru Rivers, while discussing the motivations behind the 1981 founding of YoCal Produce Cooperative.

Now as then, the logistics of moving farm-fresh products from fields to markets — not only transportation, but also cold storage, marketing, sales and food safety coordination — can present a challenge for many small-scale farmers.

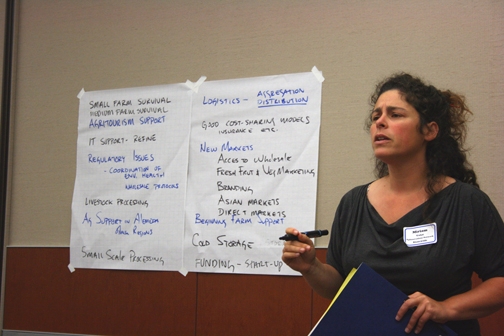

Collaboration as a way to meet these needs was the topic of the Collaborating to Access New Markets workshop, which brought together about 40 beginning farmers, experienced farmers, entrepreneurs, students and agricultural professionals June 29 in Woodland.

“Small-scale farmers can accomplish things as a group that sometimes they cannot do as individuals,” said Shermain Hardesty, Small Farm Program director and former director of the Rural Cooperatives Center. “We’re not trying to push the cooperative structure specifically, but just to look at ways that farmers might be able to work together in addressing marketing challenges.”

The day included the first complete history of the pioneering YoCal Produce Cooperative as well as a featured speaker from Pennsylvania, Jim Crawford, who discussed the long-term success of the East Coast’s largest organic produce cooperative.

Hardesty highlighted two critical lessons from collaborative ventures discussed that day, specifically: the importance of collaborative members investing financially in their joint operation and the importance of hiring the right staff, particularly managers.

Farmers Jeff Main of Good Humus Produce and Dru Rivers of Full Belly Farm discussed their experiences as founders of YoCal Produce Cooperative.

“We needed to be able to say ‘You need to pay us before we deliver to you again,’” Rivers said. “As one farmer, that doesn’t work, but as 10 farmers that does work.”

Besides strengthening the farmers’ collective voice and sharing transportation, she also highlighted access to new markets and coordinated crop production as important reasons she and others started the cooperative.

Though no longer in operation, YoCal’s decade of collaboration helped increase the viability of many Capay Valley farms and led to many of the group agricultural ventures currently in the region.

Rivers later shared with the audience insights into the current Capay Valley Farm Shop venture, which started as a brick-and-mortar store but has transitioned into a collaborative CSA that serves corporations in the Bay Area. The Capay Valley Farm Shop is not a cooperative, but does serve some marketing needs for participating farmers.

Jim Crawford shared his more than two decades’ worth of experience leading a collaborative marketing service, Tuscarora Organic Growers. This cooperative is owned entirely by member farmers who share the costs of shipping and marketing to retail grocery stores, food co-ops and restaurants in the Washington, D.C., metro area. The cooperative currently works with more than 50 producers to distribute about 100,000 cases of fresh produce and flowers each year.

But when the cooperative held its first meeting in 1988, there were only five growers and they were unable to secure financing for their venture. They decided to try sharing marketing and sales with some extra capacity offered by Crawford’s own New Morning Farm — including cooling space, trucking capacity, an office and a part-time employee.

“One of our strong points [is] our growth has been steady but slow. We never had one of those times of explosive growth,” Crawford explained.

Crawford identified several other aspects of Tuscarora Organic Growers that he believes helped it succeed from its early days, including grower need, a clear and narrow definition, a strong manager, a founding farm that could spearhead support for the co-op, and diverse growers.

The event ended with a brainstorming session, with break-out groups for beginning farmers, experienced farmers and support professionals.

Participant Vonita Murray started her Mariposa Valley Farm this year, selling produce at the Woodland Farmers Market and working to start a CSA. She is still working a part-time job in addition to farming. “I honestly don’t know how I’m going to survive” as a farmer, she said.

By the end of the workshop, Murray had met neighbors and found some new ideas.

“I know a lot of other small farmers with 3 acres or 4 acres, and I know my next step is to talk to them and see how we can share and collaborate,” she said.

Major accomplishments of YoCal Produce Cooperative

- Marketing and trucking: Collaborating on these tasks allowed farmers the time to grow their farms, sell in the wider market, and be able to make a living. The farmers no longer had to farm all day and drive all night or have one partner support the farm with an off-farm job. “It gave us the confidence that we could make it as small farmers without having another job,” said one member.

- Market entry and increased impact: The cooperative provided entry into the wholesale fresh produce market for some growers and increased market power in the wholesale fresh produce market for others. YoCal raised the visibility of smaller farms, increasing the impact of individual brands by co-marketing under the YoCal label. It eased the growth of several farmers who wanted to grow larger. It was a good transition strategy for them.

- Planning to avoid competition: Although not developed as fully as some members would have liked, the group was able to coordinate some multi-farm plantings and grow some crops recommended by distributor partners.

- Grower education: YoCal improved quality, pack and presentation of product at a time when the organic produce industry was in its formative years. Members learned much about cooperative decision making and how to most efficiently spend their time and energy.

- A sense of community: “We got to know farmers we might not have met otherwise,” said one member. YoCal pulled a divergent group of farmers together and gave them a cohesiveness that they probably would never have developed without it. “Major accomplishments for us, as individuals, are that we, as a community of farmers, are still doing cooperative things together,” said another.

- A model: YoCal was one of the first organic marketing cooperatives in modern times.

– excerpt from "YoCal Produce Cooperative:

The Growers’ Story and the Cooperative Principles"

- Author: Brenda Dawson

There was a surprise waiting for the food safety auditor when he looked around for signs of wildlife, though the farmer had told him his farm didn’t have any rodent problems. Under a bin were some tunnels, one of which contained a dead mouse.

“You don’t want an inspector to find a dead mouse 6 feet from your strawberries,” said Richard Molinar, UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor, in recounting the story. “First you need to think about everything in the field, but then you also have to be aware of burrows in your neighbor’s field.”

Surprises like these could lose a farmer points — or even mean failure — in a food safety audit. But this was just a test, a mock audit to help farmers better prepare their own food safety plans.

Background

Focus on food safety — through education, market demand and legislation — has been ramping up since 2007, after E. coli contamination of spinach grown in Salinas. In January of this year, the Food Safety Modernization Act was signed into law, which includes an exemption for growers with annual sales of less than $500,000, if the majority of sales are made directly to local consumers, restaurants or stores. And in late April, USDA formally proposed a national leafy greens marketing agreement similar to the California LGMA already in place.

Though some small farms are exempt from food safety legislation or major marketing agreements, their buyers may still require they adopt and adhere to a food safety plan.

In September 2010 Molinar heard a local packinghouse that contracts with many small-scale growers in Fresno County was requiring all their farmers have a food safety manual.

“And it’s not just [this grower-packer-shipper] and their buyers. It’s many other retailers, wholesalers and processors too,” Molinar said. “It’s really buyer- and consumer-driven, so [for now] it doesn’t matter what FDA or USDA comes up with. If the consumer or the buyer wants to see a food safety program, the farmers and the packers have to come up with it.”

Developing a manual

Since 2007, Molinar has held meetings to educate growers abut food safety, and in 2009 he began working with Jennifer Sowerwine and Christy Getz, both of UC Berkeley, to develop a food safety manual that could help farmers get started.

The manual provides a framework for a food safety plan, with information about standard operating procedures, worker training and recordkeeping. The manual must be personalized to the farm, implemented and documented.

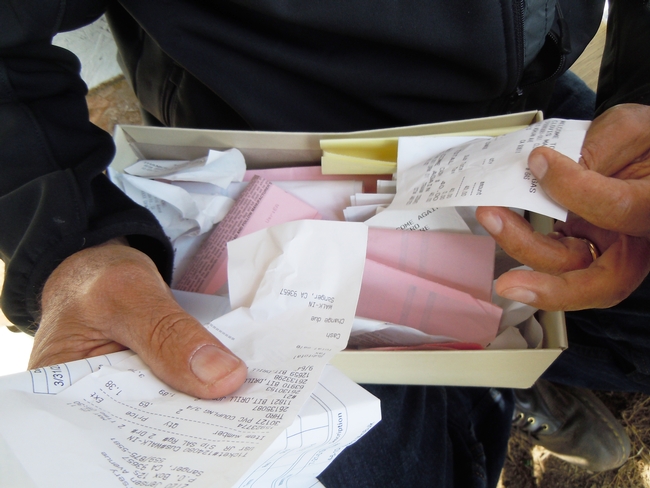

“We wanted something really basic that we could use for small-scale farmers,” Molinar said. “Larger, corporate farms can afford to hire a person to do this for them and have a more complex document. We’re trying to come up with something very simple, but even this one still requires some paperwork and filing documents in the correct part of a binder with envelopes and receipts.”

The manual also requires some decision-making on the part of the farmer, most likely informed by demands of potential buyers.

“Right now it’s so new that for most of the crops — except for leafy greens or fresh-market tomatoes — there aren’t specific guidelines or standards,” he said. But having a basic food safety manual in place for the farm is fairly easy and keeps the farm competitive.

Mock audits

Certain buyers or groups may require that farmers have their food safety practices audited. Third-party food safety audits can attest to whether the farm is adhering to its food safety manual and can identify when the plan, related actions or documentation fall short of good agricultural practices (GAPs).

Though private firms can conduct these audits, the California Department of Food and Agriculture also performs verification audits in relation to food safety.

To help educate the region’s farmers, CDFA agreed to do some mock audits on Fresno area farms to help prepare farmers. A handful of mock audits have been conducted with small groups attending to observe.

“Farmers right now do not have to be audited by a third party — that’s up to the buyer — but they should at least have some sort of food safety manual,” Molinar said. “Even though third-party audits aren’t required, we thought it was a good way for farmers to start learning about food safety and look at some of the questions that would be asked.”

Lessons learned from the mock audits can save time, money and embarrassment down the road.

“In the first audit we did, the farmer pulled out a shoebox of receipts, and they weren’t organized. So the auditor is thumbing through the box to look for the receipt,” Molinar said. “You need to be organized because you’re paying the auditor by the hour.”

Increasing market competitiveness

Having a food safety plan in place can certainly improve safety and reduce risk, but it can also make it easier to sell to new buyers who are interested in food safety documentation.

“The main goal is to have our farmers in Fresno — and statewide — ahead of the game in food safety, so that buyers and consumers can be assured that their food is safe,” Molinar said. “It will give our farmers a marketing advantage if they have a food safety program in place because that’s what buyers and consumers want to see.”

Read the rest of Small Farm News, Vol. 1 2011.

- Author: Brenda Dawson

In case you missed it, here is our traditional PDF newsletter, also called Small Farm News.

For a few years, we encouraged subscribers to consider switching to an email version of the newsletter, delivered as a PDF. But with the evaporation of funding, money for printing and mailing (and even creating) a newsletter are now simply gone.

The newsletter is no longer quarterly. And it is no longer printed nor mailed.

But we're happy to send it to your Inbox!

Please help us share the word with folks who subscribed to Small Farm News by mail that they should sign up for an email subscription to continue receiving the newsletter. New subscribers are welcome too!

And in the meantime, find out the latest news and research related to California's small-scale farms when it comes to food safety, collaboration, agritourism, new books, blueberries, and low-water cropping right here in this PDF.

- Author: Brenda Dawson

Before you can plant vegetables for a field experiment, you will need ... a field to plant them in. Sure, you'll also need a seed or a plant, some tools, some knowledge and a variety of other things.

But definitely before you can plant anything, you need somewhere to plant it. Sometimes the "where" of planting is in a pot, in a greenhouse or in a garden.

Many farm advisors — including some who work with the UC Small Farm Program — are able to plant experimental field plots at one of the nine "Research and Extension Centers" that are operated by the University of California. (Remember this video with colorful carrots and giant radishes? It was filmed at the UC Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center.)

But other farm advisors don't have access to a field station, so they work with local farmers who agree to allow the farm advisor to use part of their fields to test plants.

For our part of the Great Veggie Adventure, farm advisors with the Small Farm Program are planting vegetables in five counties in different parts of California — some at a Research and Extension Center, and others at cooperating farms.

In Santa Barbara County, Mark Gaskell has worked with a cooperating farm called Growing Grounds. Growing Grounds farm in Santa Maria is a non-profit farm and wholesale nursery that provides horticultural therapy and job training to mental health patients.

Recently I had the chance to visit Mark and get a tour of Growing Grounds from Ariella Gottschalk, the farm's program manager.

Mark and Ariella showed me rows of vegetables and flowers, a brightly painted farm stand and even some chickens. Then they picked some of the vegetables that were almost ready for harvest, to see how well the plants were growing.

When I visited, the farm had different rows of colorful carrots that had been planted during different months. Many of the carrots in the field were still too young and too small for harvest — some were smaller than my pinky finger!

I also had the chance to talk with Mark about some of the basic science behind field experiments like this one. One of the questions I asked Mark was: Why do we need to keep planting those vegetables over and over again, and in five different locations around the state? Play the video above to hear what Mark had to say.

University of California Research and Extension Centers

... or have a question? Ask away.