All Issues

Grower beliefs determine hiring practices

Publication Information

California Agriculture 50(2):17-20. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v050n02p17

Published March 01, 1996

Abstract

The use of farm labor contractors (FLCs) has increased over the last decade. Of 51 Fresno County growers surveyed, at least half had used an FLC by 1991; one-third had done so by 1985. The objective of this study was to find out why some growers use FLCs, while others prefer to hire workers directly. Although grower profiles do not differ markedly, the two groups hold different perceptions about the advantages of each labor group. Direct-hire growers rate direct-hire workers higher on quality of work and productivity, whereas indirect-hire growers list reliability of labor source as a critical factor influencing their decision.

Full text

The randomly selected growers included stone-fruit and raisin-grape growers. Of all the growers, 59% used at least some farm labor contractor crews.

Why do some farmers hire all their workers directly while others obtain at least some workers from farm labor contractors (FLCs)? Why are more growers using FLCs today than a decade ago? To answer these questions, we surveyed 51 Fresno County growers in 1992-1993 about the 1990-1991 crop year. The randomly selected growers included 21 stone-fruit (nectarines, peaches, and plums) growers and 30 raisin-grape growers. Of all the growers, 21 (41%) were direct-hire growers — who hired all their own workers — and 30 (59%) were indirect-hire growers — who used at least some FLC crews. Farmers who used both tended to use direct-hire workers for one task or crop, and FLC laborers for another.

Grower characteristics

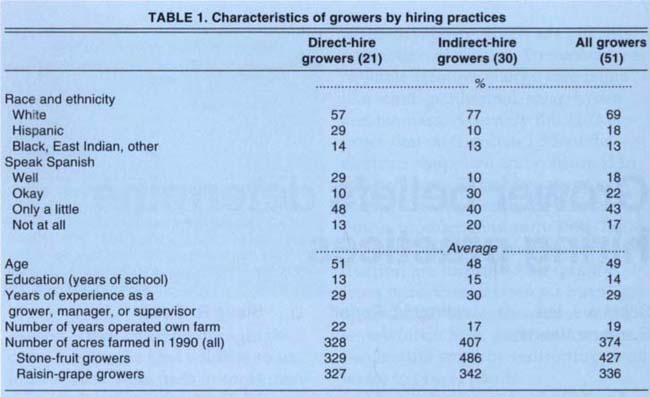

We examined two possible explanations for the hiring preferences of both types of growers. One explanation is the two types of growers differ in characteristics such as age, experience and ethnicity. The other is that growers have different perceptions about direct-hire versus FLC labor. While one might expect growers to choose an FLC if the growers are of a different ethnicity than the workers, are relatively inexperienced or do not speak Spanish, we found few differences in characteristics of both direct-hire and indirect-hire growers (table 1).

As table 1 shows, direct-hire and indirect-hire growers were similar in many ways.

The typical grower was a 49-year-old, non-Hispanic white male. (Many of these “growers” were actually husband-wife teams; however, only one — typically the husband — was listed as the grower in the County Agricultural Commissioner's list.) Of the direct-hire growers, 57% were white compared to 77% of indirect-hire growers. Due to the relatively small sample, however, these differences were not statistically significant and could be explained by chance alone.

While one might expect inexperienced growers to be more likely to use an FLC, we found experience played little part in hiring decisions. Both groups had on average three decades of experience as a manager, supervisor or grower. Moreover, both groups had owned their own farms for decades: Direct-hire growers had operated their own farms for an average of 22 years compared to 17 years for indirect-hire growers.

Similarly, we found little difference in education: the average grower in the survey had completed 2 years of college.

The most striking difference in grower characteristics was the ability to communicate with workers in their native language. Of all growers, 90% said English was their main language; 4%, Spanish; and 6%, other. Forty percent spoke Spanish well or at least “OK.” Those growers who said they spoke Spanish well were more likely to hire directly. These differences were not statistically significant, however.

One might expect larger farms, which need more workers, to rely more heavily on FLCs. The direct-hire growers had smaller farms — 328 acres on average compared to 407 acres for those that use FLCs — but this difference was not statistically significant. Thus differences in growers' hiring practices cannot be explained by differences in grower characteristics.

Rating quality of work forces

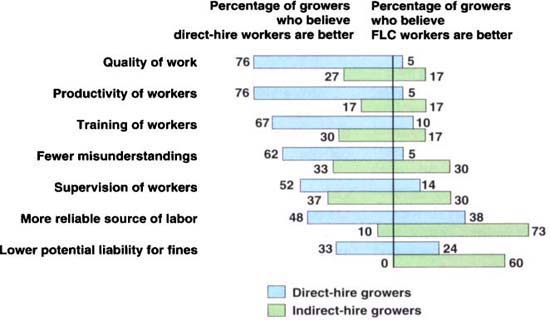

One reason only some growers use FLCs may have to do with different beliefs about the quality and costs of the two types of work forces. To find out if they held different beliefs, we asked both grower groups to compare characteristics of direct-hire and FLC workers.

On the seven criteria listed in figure 1, the majority of direct-hire growers rated direct-hire workers higher than FLC workers. Indirect-hire growers tended to rank FLC workers equal to or higher than direct-hire workers.

Quality of work and productivity were two characteristics for which most direct-hire growers ranked direct-hire workers superior. Three-fourths (76%) of direct-hire growers felt that direct-hire employees produced higher-quality work, 5% thought FLC workers were better, 14% felt there was no difference and 5% had no opinion. In contrast, only 17% of indirect-hire growers thought FLC workers produced higher-quality work; 27% felt that direct-hire workers were better, 47% felt there was no difference, and 9% had no opinion.

Three-fourths of the direct-hire growers also thought direct-hire workers were more productive. In contrast, only 17% of indirect-hire growers thought FLC workers were more productive. Sixty percent of indirect-hire growers thought the two groups were equally productive, compared to 19% of direct-hire employers.

Nearly two-thirds of direct-hire growers believed that fewer misunderstandings occurred with direct-hire workers, and virtually none thought there were fewer misunderstandings with FLC workers. One-third of indirect-hire growers thought there were fewer misunderstandings with FLC workers, one-third with direct-hire workers, and one-third thought there was no difference.

FLC workers were rated as a more reliable source of labor by 73% of indirect-hire growers and 38% of direct-hire growers. In contrast, 48% of the direct-hire growers and 10% of the indirect-hire growers thought direct-hire employees were a more reliable source.

Perhaps more important, one-third of direct-hire growers believed that using direct-hire workers lowered their potential liability for labor law violations, while none of the indirect-hire growers concurred. One-quarter of direct-hire growers believed that using FLC workers was less likely to lead to liability problems, whereas 60% of indirect-hire growers believed this to be true.

Most growers believed that wage costs for both types of workers were identical, but that total costs were a little higher for an FLC work force. Total costs include FLC commission, wages, benefits, payroll taxes, management costs, tools and equipment.

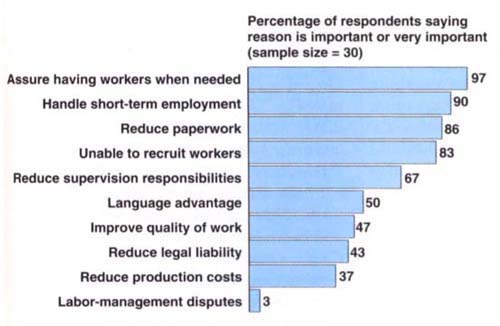

Why growers used FLCs

The key reasons indirect-hire growers gave for using FLCs are shown in figure 2. Availability of workers when needed was given as the most important reason. Other leading considerations were handling of short-term employment, reducing paperwork, and eliminating the need to recruit workers. Reduced supervisory responsibilities, less legal liability, elimination of language problems and improved quality of work also were named as important considerations by some growers. Labor-management disputes or the threat of union organizing were relatively unimportant.

Fig. 1. Growers' perceptions of relative quality of direct-hire and FLC workers by growers' hiring practices.

Changes over time

The number of tree-fruit and raisin-grape growers using FLCs has increased significantly in the last decade. Before 1985, two-thirds of the growers had never used an FLC (64% of the stone-fruit growers and 65% of the raisin-grape growers). By 1991, about half of the growers reported they had used FLC crews. For stone-fruit growers, 1988 was the most commonly reported year in which an FLC was first hired. For raisin growers, the two most commonly reported years were 1980 or 1987.

Two factors appear to have influenced growers' decisions to increase their use of FLC workers or to rely more on direct hiring. These factors were changes in labor laws — which increased bookkeeping responsibilities and legal liabilities — and the need for a reliable source of labor.

Changes in labor laws

Three laws passed over the last two decades have increased the bookkeeping responsibilities and other liabilities of California growers. The California Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA) of 1975 requires employers to bargain collectively with a union that has been elected as representative of workers at the farm, and also prohibits employers and unions from committing unfair labor practices. This act made growers responsible for unfair labor practices of FLCs while they are working for the grower.

The 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which became effective on December 1, 1988, requires employers to check workers' eligibility to work in the United States and to fill out and maintain a form for each employee.

In 1989, the California legislature passed SB 198, which went into effect July 1, 1991, and requires employers to establish a written injury and illness prevention program. These three laws may have prompted some growers to hire more FLC workers in an attempt to avoid liability problems.

Finding a reliable source of labor

Growers need a reliable source of labor to perform work on seasonal crops in a timely manner. Those who find it difficult to hire enough workers at crucial times of the year may be more likely to use an FLC.

To manage the work force effectively, many growers need a reliable manager or foreman or a good working relationship with an FLC. Indirect-hire growers in our survey tended to rely on the same FLCs every year. Of stone-fruit growers who used FLCs, 69% hired only one FLC in 1990 and 23% hired just three. Similarly, of indirect-hire raisin-grape growers, 59% hired just one FLC and 18% hired two. In 1990, two-thirds of all growers rehired one or more FLCs who had worked for them at least 3 years before. Most stone-fruit growers (83%) and raisin-grape growers (65%) did not hire any new FLCs in 1990. This pattern demonstrates stability in year-to-year business arrangements between growers and FLCs.

Although one might imagine that some growers chose not to use FLCs because they were unfamiliar with them, this explanation appears to be false. The vast majority — 81% of stone-fruit growers and 86% of raisin-grape growers we surveyed — had hired an FLC at some time in the past.

Growers' explanations

We asked growers to rate (on a scale that ranges from 1 = unimportant, to 5 = very important) the importance of various factors contributing to their decision to hire a larger proportion of FLC or direct-hire labor in 1991 than in previous years.

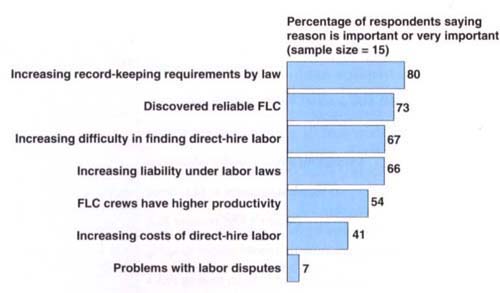

The top three reasons growers gave for employing more FLC labor, as shown in figure 3, were increased burden from record-keeping requirements, found reliable FLCs and increased difficulty in finding laborers.

Three-fourths of direct-hire growers felt that direct-hire workers produced higher-quality work. In contrast, 27% of growers who use farm labor contractors felt that direct-hire workers were better.

When asked directly, the majority of growers said the three major new labor laws had relatively little effect on their hiring decisions. However, approximately one-third said they were influenced by SB 198 another one-third influenced by IRCA. Moreover, as shown in figure 3, the majority of growers who increased their use of FLC labor cited increased bookkeeping responsibilities and legal liability as key reasons. None of the growers cited “labor disputes and union organizing in the area” as an important factor. This response may reflect the low levels of union organizing during this period.

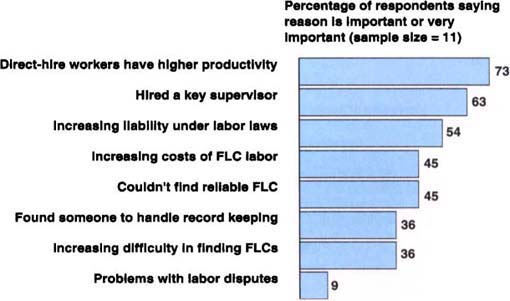

The perceived reliability of FLCs was a key factor in deciding to hire more direct-hire labor (fig. 4). The presence of a key supervisor or foreman was a moderately important reason for growers who hired more direct-hire employees in 1991, but the absence of one was not listed as an important reason for hiring more FLC workers.

Growers who increased their use of FLC labor did so for different reasons than those who increased direct hiring (figs. 3 and 4). Growers who relied more heavily on an FLC work force worried about increased liability or had found a reliable FLC. Growers who increased their direct hires did so because they were dissatisfied with their FLC, the FLC's workers or the FLC's costs.

Hiring depends on beliefs

We found few obvious differences in characteristics between direct-hire and indirect-hire growers in our Fresno County survey. Both types of growers had, on average, the same years of experience, education, and age. Indirect-hire growers tended to have slightly larger farms, although this difference was not statistically significant. Hispanic growers and those who spoke Spanish well were more likely to hire directly.

However, the growers differed substantially in their beliefs about the quality of the two labor forces. Most direct-hire growers believed that direct-hire workers produced higher-quality work, while indirect-hire growers saw less of a difference. Most growers believed that wage costs for both types of workers were identical, but that total costs were a little higher for an FLC work force. The main reasons indirect-hire growers gave for using FLCs were to ensure having workers when needed, to reduce paperwork, and to avoid recruiting workers.

The use of FLC labor has increased over time. This change may be due in part to changes in bookkeeping requirements and legal liabilities due to new labor laws, and also to growers' procurement of reliable FLCs. Growers who used more FLC labor usually attributed this shift to the discovery of a reliable FLC. Those growers who increasingly hired directly emphasized the higher productivity of direct-hire workers, the inability to find a reliable FLC and increased FLC costs.