A petition spearheaded by Thorp and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation to list Franklin’s bumble bee under the National Endangered Species Act has moved to the next step in the process, the 12-month review period. This may lead to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) listing it as “endangered” and providing protective status.

The bad news: Thorp hasn’t seen Franklin’s bumble bee since 2006.

“I am still hopeful that Franklin’s bumble bee is still out there somewhere,” said Thorp, emeritus professor of entomology. “Over the last 13 years I have watched the populations of this bumble bee decline precipitously. My hope is this species can recover before it is too late."

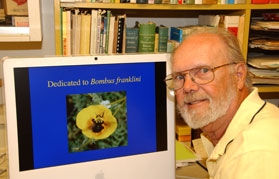

Thorp researches the declining population of Franklin’s bumble bee, Bombus franklini (Frison), found only in a narrow range of southern Oregon and northern California. Its range, a 13,300-square-mile area confined to Siskiyou and Trinity counties in California; and Jackson, Douglas and Josephine counties in Oregon, is thought to be the smallest of any other bumble bee in North America and the world.

Thorp’s surveys, conducted since 1998 clearly show the declining population. Sightings decreased from 94 in 1998 to 20 in 1999 to 9 in 2000 to one in 2001. Sightings increased slightly to 20 in 2002, but dropped to three in 2003. Thorp saw none in 2004 and 2005; one in 2006; and none since.

“My experience with the Western bumble bee (B. occidentalis) indicates that populations can remain ‘under the radar’ for long periods of time when their numbers are low,” he said. Thorp did not see the Western bumble bee between 2002-2008, but now, although sightings are rare, they are “consistently encountered.”

This year Thorp surveyed the bumble bee's historic sites in southern Oregon and northern California on five separate trips of several days each: two in June and one each in July, August and September. "Flowering and bumble bee phenology were pushed back about a month this year due to our cold wet spring," he said. " I managed to see and photograph workers of B. occidentalis at two sites on my August trip. I had hoped to see males and even a Franklin’s on my last visit in September, but alas no luck."

"However, flowering was more like mid-August and lots of other species of worker bumble bees were still foraging," he noted. "Males and new queens were also on the wing. The new queens will mate and hibernate to emerge and produce new colonies next year. The old queens and the rest of this year's colony members will die out soon, as this season winds to a close."

Thorp and the Xerces Society petitioned USFWS on June 23, 2010 for endangered status for the bumble bee. Today (Sept. 13) USFWS announced “Based on our review, we find that the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that listing this species may be warranted. Therefore, with publication of this notice we are initiating a review of the status of the species to determine if listing the Franklin’s bumble bee is warranted that Franklin's bumble bee may warrant protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.”

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the world’s oldest and largest global environmental network, named Franklin’s bumble bee “Species of the Day” on Oct. 21, 2010. IUCN placed it on the “Red List of Threatened Species” and classified it as “critically endangered” and in “imminent danger of extinction.”

Franklin's bumble bee, mostly black, has distinctive yellow markings on the front of its thorax and top of its head, Thorp said. It has a solid black abdomen with just a touch of white at the tip, and an inverted U-shaped design between its wing bases.

“This bumble bee is partly at risk because of its very small range of distribution,” he said. “Adverse effects within this narrow range can have a much greater effect on it than on more widespread bumble bees.”

If it’s given protective status, this could “stimulate research into the probable causes of its decline,” said Thorp, an active member of The Xerces Society. “This may not only lead to its recovery, but also help us better understand environmental threats to pollinators and how to prevent them in future. This petition also serves as a wake-up call to the importance of pollinators and the need to provide protections from the various threats to the health of their populations.”

Thorp hypothesizes that the decline of the subgenus Bombus (including B. franklini and its closely related B. occidentalis, and two eastern species B. affinis and B. terricola) is linked to an exotic disease (or diseases) associated with the trafficking of commercially produced bumble bees for pollination of greenhouse tomatoes.

Other threats may include pesticides, climate change and competition with nonnative bees, according to the Xerces Society executive director Scott Hoffman Black. Said Sarina Jepson, endangered species program director at the Xerces Society: "Bumble bees play a critical role in ecosystems as pollinators of wildflowers, as well as many crops. We hope that the service will ultimately provide Endangered Species Act protection to this important pollinator."

Named in 1921 for Henry J. Franklin, who monographed the bumble bees of North and South America in 1912-13, Franklin’s bumble bee frequents California poppies, lupines, vetch, wild roses, blackberries, clover, sweet peas, horsemint and mountain penny royal during its flight season, from mid-May through September. It collects pollen primarily from lupines and poppies and gathers nectar mainly from mints.

According to a Xerces Society press release, bumble bees are declining throughout the world.

Researchers in Britain and the Netherlands have “noticed a decline in the abundance of certain plants where multiple bee species have also declined. For many crops, such as greenhouse tomatoes, blueberries and cranberries, bumble bees are better pollinators than honey bees, and some species are produced commercially for their use in pollination. ”

Last October Thorp received a 2010-11 Edward A. Dickson Emeriti Professorship Award, from UC Davis to support his research on the critically imperiled bumble bee. The objectives of Thorp’s research funded by the Dickson grant are to:

- Collect bumble bees for disease studies at the University of Illinois with emphasis on B. franklini (where and when appropriate so as not to hinder population recovery) and B. occidentalis and potential reservoir species known to co-occur with them, all within the historic range of B. franklini.

- Survey for B. franklini and B. occidentalis with emphasis on B. franklini historical sites.

- Include observations on population abundance of other species of bumble bees at monitoring sites for comparison with the two target species.

- Monitor floral visitation and track any individuals of B. franklini and/or B. occidentalis to determine their foraging behavior, subset of overall habitat used, nest site locations, and acceptance of trap-nest boxes.

Thorp, a fellow of the California Academy of Sciences, teaches “The Bee Course” every summer for the American Museum of Natural History of New York at its field station in Arizona.

(Editor's Note: The Xerces Society contributed to this news release. See UC Davis Department of Entomology website at http://entomology.ucdavis.edu/news/franklinbumblebee.html for larger version of Franklin's bumble bee)