- Author: Bryon J. Noel

Hello everyone, I hope you are all healthy, safe, sane, and if possible, being productive.

Here I provide a summary of some of the mapping technology that has been used in the past few weeks to understand the COVID-19 pandemic.

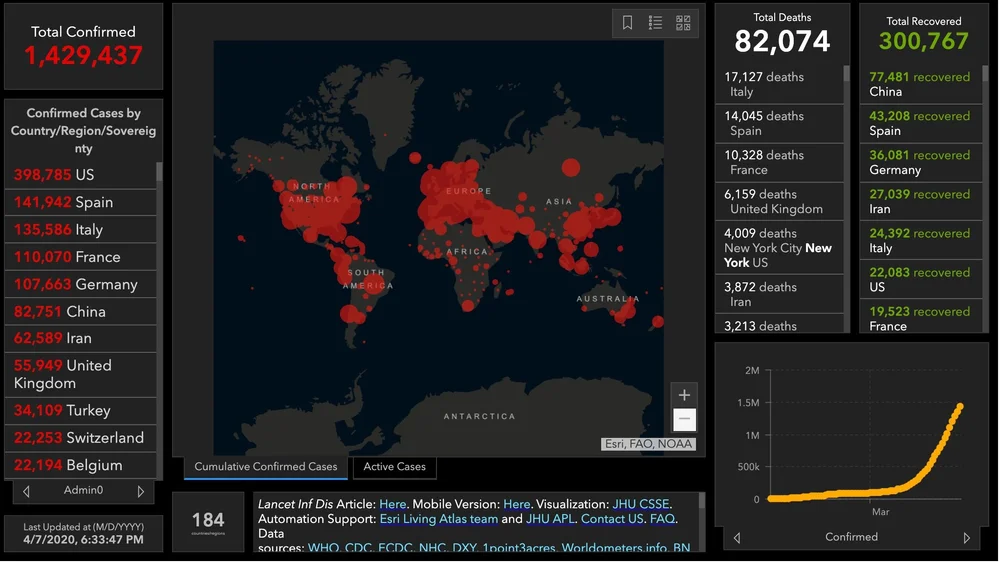

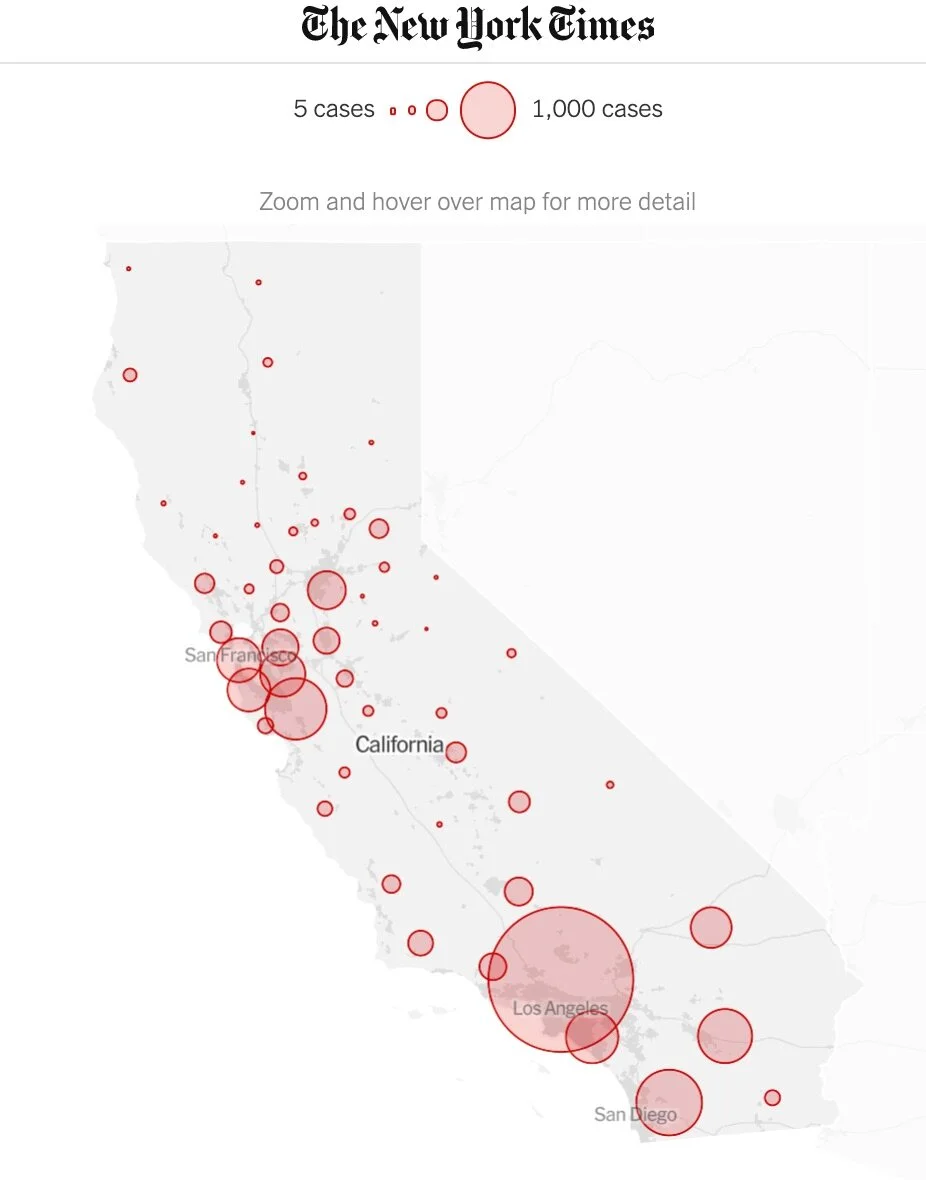

COVID-19 map-based data dashboards. You have seen these: lovely dashboards displaying interactive maps, charts, and graphs that are updated daily. They tell an important story well. They usually have multiple panels, each visualizing a dataset in either map or graph or tabular form. There are many many data dashboards out there. My two favorites are the Johns Hopkins site, and the NYTimes coronavirus outbreak hub.

Where do these sites get their data?

Most of these sites are using data from similar sources. They use data on number of cases, deaths, and recoveries per day. Most sites credit WHO, US CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control), Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC), and other sources. Finding the data is not always straightforward. An interesting article came out in the NYTimes about their mapping efforts in California, and why the state is such a challenging case. They describe how “each county reports data a little differently. Some sites offer detailed data dashboards, such as Santa Clara and Sonoma counties. Other county health departments, like Kern County, put those data in images or PDF pages, which can be harder to extract data from, and some counties publish data in tabular form”. Alameda County, where I live, reports positive cases and deaths each day, but they exclude the city of Berkeley (where I live), so the NYTimes team has to scrape the county and city reports and then combine the data. Some of the sites turn around a release their curated data to us. JH does this (GitHub), as does NYTimes.

But… all these dashboards are using simple data: number of patients, number of deaths, and number recovered, summarized by some spatial aggregation. In the US, this is usually by county.

How do these sites create data dashboards?

The summarized data by County or Country can be visualized in mapped form on a website via web services. These bits of code allow users to consume and display datasets from different sources in mapped form without having to host or process them. In short, any data with a geographic location can be linked to a web map and embedded in a website; charts and tables are also done this way. Many of the dashboards out there use ESRI technology to do this. They use ArcGIS Online, which is a powerful web stack that quite easily creates mapping and charting dashboards. The Johns Hopkins site uses ArcGIS Online, WHO does too. There are over 250 sites in the US alone that use ArcGIS Online for mapping data related to COVID-19. Other sites use open source or other software to do the same thing. The NYTimes uses an open source mapping platform called MapBox to create their custom maps.

An open access peer reviewed paper just came out that describes some of these sites, and the methods behind them. Kamel Boulos and Geraghty, 2020.

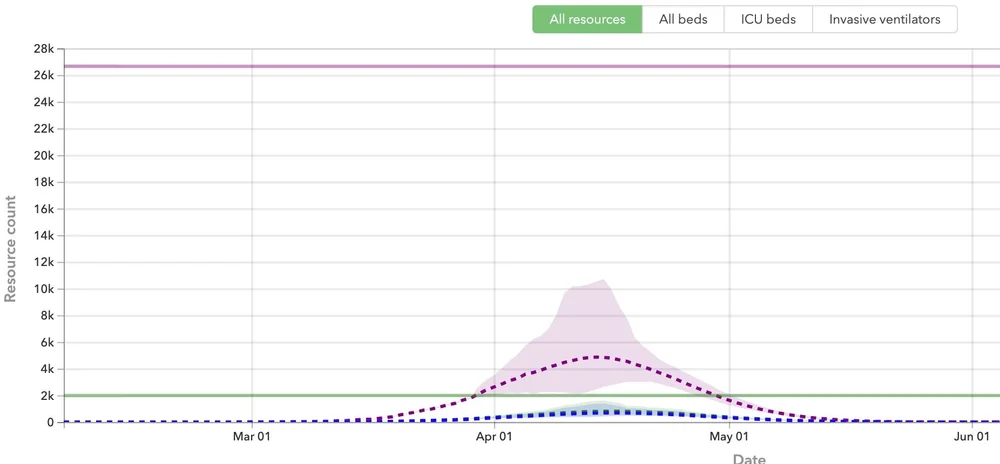

COVID-19 disease projections. There are also sites that provide projections of peak cases and capacity for things like hospital beds. These are really important as they can help hospitals and health systems prepare for the surge of COVID-19 patients over the coming weeks. Here is my favorite one:

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) provides a very good visualization of their statistical model forecasting COVID-19 patients and hospital utilization against capacity by state for the US over the next 4 months. The model looks at the timing of new COVID-19 patients in comparison to local hospital capacity (regular beds, ICU beds, ventilators). The model helps us to see if we are “flattening the curve” and how far off we are from the peak in cases. I’ve found this very informative and somewhat reassuring, at least for California. According to the site, we are doing a good job in California of flattening the curve, and our peak (projected to be on April 14), should still be small enough so that we have enough beds and ventilators. Still, some are saying this model is overly optimistic. And of course keep washing those hands and staying home.

Where do these sites get their data?

The IHME team state that their data come from local and national governments, hospital networks like the University of Washington, the American Hospital Association, the World Health Organization, and a range of other sources.

How do the models work?

The IHME team used a statistical model that works directly with the existing death rate data. The model uses the empirically observed COVID-19 population and calculates forecasts for population death rates (with uncertainty) for deaths and for health service resource needs and compare these to available resources in the US. Their pre-print explaining the method is here.

On a related note, ESRI posted a nice webinar with Lauren Bennet (spatial stats guru and all-around-amazing person) showing how the COVID-19 Hospital Impact Model for Epidemics (CHIME) model has been integrated into ArcGIS Pro. The CHIME model is from Penn, and it takes a different approach than the IHME model above. CHIME is a SIR (susceptible-infected-recovery) model. These models estimate the probability of an individual moving from susceptible to infected, and then to a recovered state or death. The incorporation of this in ArcGIS Pro looks very useful, as you can examine results in mapped form, and change how variables (such as social distancing) might change outcomes. Her webinar is here.

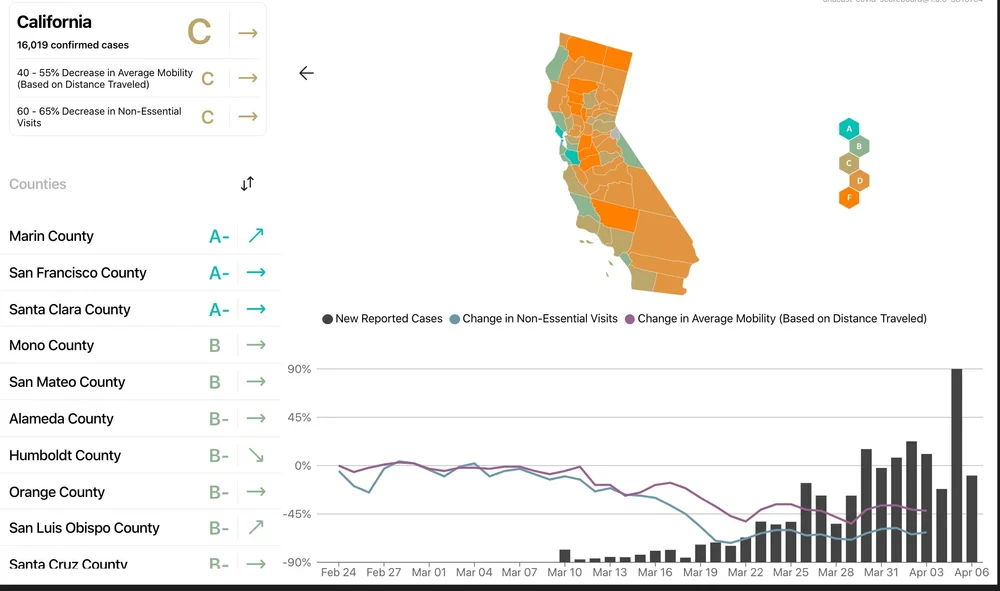

Social distancing scorecards. This site from Unicast got a lot of press recently when it published a scoreboard for how well we are social distancing under pandemic rules. In their initial model, social distancing = decrease in distance traveled, as in, if you are still moving around as you were before the pandemic, then you are not socially distancing. There are some problems with this assumption of course. As I look out on my street now, I see people walking, most with masks, and no one within 10 feet of another. Social distancing in action. These issues were considered, and they updated their scorecard method. Now, in addition to reduction in distance traveled, they also include a second metric to social distancing scoring: reduction in visits to non-essential venues. Since I last blogged about this site nearly two weeks ago, California’s score went from an A- to a C. Alameda County, where I live, went from an A to a B-. They do point out that drops in scores might be a result of their new method, so pay attention to the score and the graph. And stay tuned! Their next metric is going to be the change rate for the number of person-to-person encounters for a given area. Wow.

Where do these sites get their data?

The data on reported cases of COVID-19 is sourced from: Corona Data Scraper (for county-level data prior to March 22) and the Johns Hopkins Github Repository (for county-level data beginning March 22 and all state-level data).

The location data is gathered from mobile devices using GPS, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi connections. They use mobile app developers and publishers, data aggregation services, and providers of location-supporting technologies. They are very clear on their privacy policy, and they do say they are open to sharing data: Contact dataforgood@unacast.com.

How does Unicast create the dashboard?

They do something similar to the dashboard sites discussed above. All the spatial data is aggregated by county, and visualized on the web using custom web design. I haven’t dug into the methods in depth yet, but I will.

Please let me know about other mapping resources out there. Stay safe and healthy. Wash those hands, stay home as much as possible, and be compassionate with your community.