Research by Jim Stapleton, a UC Cooperative Extension advisor based at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center, was published as Feasibility of solar tents for inactivating weedy plant propagative material in the March 2012 issue of the Journal of Pest Science.

Stapleton, who specializes in plant pathology and integrated pest management, was inspired to conduct the study when a fire crew came upon a patch of Iberian starthistle growing along a stream in the Sierra foothills near Mariposa. Iberian starthistle is a robust, spiny weed native to the Middle East that, left unchecked, can dominate entire landscapes.

“Crews were going through and cutting dried plants and stacking them, but the seeds survived,” Stapleton said. “If you start moving plant material around with viable seeds, seeds are liable to spread, making the problem worse instead of better.”

Iberian starthistle is only one of many exotic, invasive plants that are capable of transforming California’s open areas into useless and unsightly tracts of land. On rangeland, for example, such weeds diminish desirable annual rangeland feed for cattle and wildlife. Weeds can shade out native wildflowers, make recreational areas inaccessible and, in dense infestations, become a fire laddering fuel.

In the past, such weeds may have been stacked and burned, but fire danger and air quality regulations have forced land managers to find alternatives.

“You wouldn’t want to try this on a 40-acre area,” Stapleton said. “Eradication of weeds with solar tents is best suited for small-scale weed infestations in warm climates.”

For the research project, Stapleton constructed three replicate solar tents with concrete rubble, mulberry shoots and clear plastic tarps. He placed johnsongrass rhizomes inside black trash bags along with about one cup of water. The sample bags were left inside the solar tents for 72 hours.

“Regardless of where you are, regardless of financial resources, you should be able to construct a solar tent,” Stapleton said. “Most of the materials needed – rocks and sticks – are easy to find on site.”

Air temperature inside the sample bags rose to 158 degrees Fahrenheit. Over the three days of the experiment, the rhizomes were exposed to temperatures 140 degrees and higher for 10 hours. None of the rhizome segments treated for three days in the solar tents sprouted. In contrast, rhizomes maintained in clear vegetable storage boxes and kept indoors for comparison all sprouted.

UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor Carl Bell, a San Diego area weed expert, tested the process in Lakeside, east of the San Diego metropolitan area, where a group of volunteers were working on restoration of the San Diego River.

“There are a lot of sites in California where volunteer groups are going into canyons and other remote spots to clean up weeds,” Bell said. “They’re going to places with no roads or trails, scrambling over rocks to clean up these areas. They could construct one of these tents and return in a week to find everything in the bags overheated to a point where seeds won’t germinate and rhizomes are dead. They only have to carry out the plastic bags and tarps.”

For the demonstration, volunteers pulled weeds and built solar tents on a parking lot. They invited the public to a workshop at the site a week later.

“When we pulled out the bags of treated material after a week of cooking, it was a gooey mass of vegetative material incapable of regenerating the weeds,” Bell said.

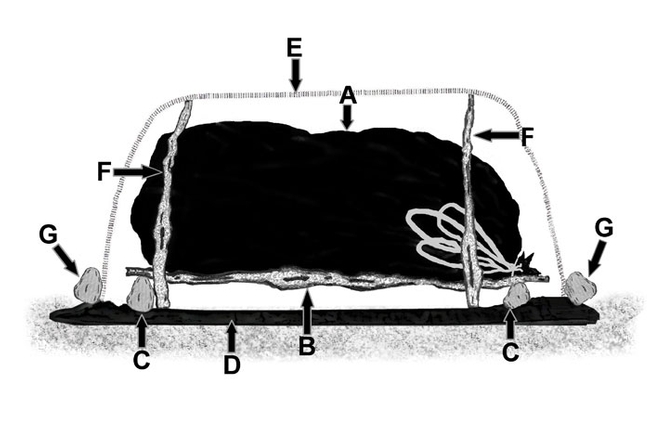

Diagram of suggested solar tent construction:

(a) closed, black plastic trash bag, e.g., 40 gal volume, containing targeted plant material and one pint to one quart of water for free moisture presence; (b) interior framework of woody plant shoots, sitting on (c) rocks, to elevate trash bag above soil surface and allow heat to surround target; (d) sheet of black plastic film on soil surface to assist with heat accumulation and preclude escape of propagative material onto the soil; (e) clear plastic sheet, supported by (f) hoops of woody plant shoots to form a tent over the treatment bag; (g) exterior rocks, soil and/or logs sealing edges of tent canopy to minimize heat loss and preclude escape of propagative material.

(Graphic by Cynthia Stapleton, adapted from Journal of Pest Science 85:17-21. Graphic may be reprinted with credit. High resolution version.)