A neighbor asked me to identify a robust perennial that keeps coming up in his garden. It had long, tropical-looking leaves and floppy racemes with small white flowers. This was a new one for me. Turned out it was common pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), a native of eastern North America. In the south some people eat it (poke salad), and a few southerners probably brought it west as a garden vegetable. But the whole plant is toxic if improperly prepared, so it’s the fugu of weeds.

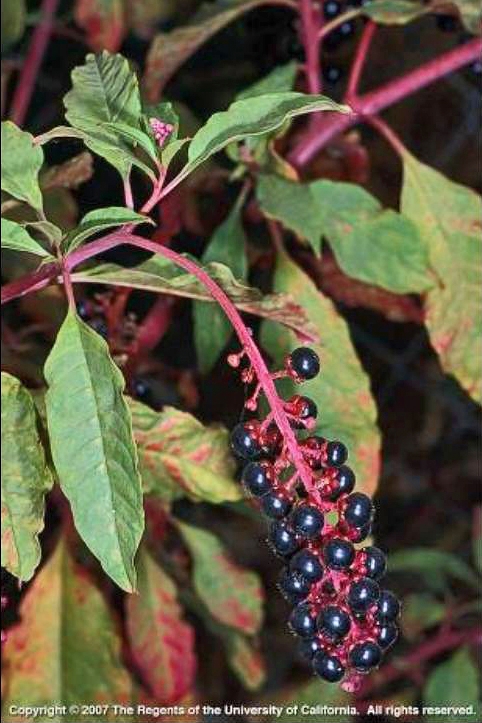

A couple of weeks later my daughter brought home a stalk of purple berries and asked if she could eat them. “No,” I said, “they contain numerous saponins and oxalates.” I began to wonder if there’s more pokeweed around than I realized.

Then Gillies Robertson of Yolo RCD sent photos of a purple-berried plant found along a slough near Grimes. Common pokeweed again.

Pokeweed is in the Phytolaccaceae. This weed can grow to 10 feet tall. It dies back in winter then reemerges from the ground in spring, growing from a fat fleshy storage root. The leaves are large, 3 inches to a foot long and 1 to 5 inches wide, often with reddish stalks and lower veins. From August to October, pokeweed produces racemes of white flowers followed by reddish-purple berries. In its natural state, all parts of the plant, especially the root, are toxic to humans. Birds can eat the berries but sometimes act funny afterwards.

This plant can be found in most of the contiguous states. In drier regions, it prefers gardens and irrigated areas. Southerners with pokeweed experience suggest controlling it by digging up as much of the taproot as possible and/or by cutting off the stalks and painting the stubs with concentrated glyphosate (e.g. Roundup). Either way, treatments will probably have to be repeated until the plant’s storage reserves are worn down. And it’s a good idea to deal with pokeweed before it produces berries and seeds.

Since this is the first year I’ve seen it, and since I suddenly ran into it in three locations within a few weeks, I’m guessing that the common pokeweed population is expanding. This plant seems robust enough to cause some trouble if it becomes established in natural riparian areas.

All photos from J.M. DiTomaso and E.A. Healy, Weeds of California and Other Western States, 2007.