Posts Tagged: David Rizzo

Community effort beats back sudden oak death in Humboldt County

UC, federal and state agencies and landowners in Humboldt County recently received national recognition for their collaborative efforts to halt the spread of sudden oak death. Kathleen Merrigan, U.S. Department of Agriculture deputy secretary, praised the partnership during her visit to Davis on May 16.

Yana Valachovic, UC Cooperative Extension advisor in Humboldt County, and Dave Rizzo, professor in the Department of Plant Pathology at UC Davis, were joined at the USDA offices in Davis by their partners from USDA Forest Service, CAL FIRE and the Natural Resources Conservation Service to accept the Two Chiefs’ Partnership Award. Merrigan presented the award on behalf of the “two chiefs” – the head of NRCS and the head of the Forest Service.

For me, it was a pleasure not just to see Yana’s efforts rewarded, but also to see Dave Rizzo. About a decade has passed since the days I was on the phone and email almost daily forwarding reporter requests for interviews to the UC Davis plant pathologist. Rizzo was first to identify Phytophthera ramorum as the pathogen that causes sudden oak death in 2000.

Although SOD doesn't make the news as frequently as it did in the early 2000s, it continues to spread. Garbelotto’s "SOD Blitz," his annual survey, found in 2011 that the rate of infection in trees between Napa and Carmel had grown as much as three times the rate of the previous year.

Since the disease was first reported in Marin County in 1995, it has been found in 14 coastal California counties and killed over 5 million tanoak, coast live oak, California black oak, Shreve oak and canyon live oak trees, according to the Forest Service.

UC Cooperative Extension employees were surprised in the spring of 2010 when routine monitoring near the mouth of Redwood Creek in Humboldt County detected P. ramorum in leaf samples. It meant that trees were infected somewhere in the 200,000-acre watershed – more than 50 miles from the nearest known infestation and farther north than the pathogen had ever been detected in California.

UCCE staff coordinated a swift management response, embarking on the largest SOD management project ever to occur in California. They collaborated with the Forest Service, NRCS, CAL FIRE, tribes, local timber companies and private landowners to remove infected plant material. Rizzo pitched in with diagnostics for the project and matching funds to qualify for a federal grant.

It’s still not clear how the pathogen got to Redwood Valley, said Valachovic, but it could threaten the dense tanoak forests of the surrounding area, killing trees and leaving behind dry brush, which could fuel wildfire.

Landowner support has been critical to the success of the project, according to Valachovic. More than 20 landowners in the valley have allowed monitoring and treatment activities on their properties, recognizing that their cooperation may keep the disease from spreading to other areas.

The first phase of treatment is currently wrapping up, and UCCE is beginning to monitor project efficacy and watch for spread of the pathogen beyond project boundaries. The Yurok and Hoopa tribes will be paying close attention to this effort, as they are only a ridge away from the infestation.

“Oaks are an important part of our culture and history, and we will do what we can to keep sudden oak death out of our forests,” says Ron Reed, a Yurok tribal forester.

Scientists, managers, regulators and policymakers will gather June 19-22, 2012, to discuss the latest news about the disease at the Fifth Sudden Oak Death Science Symposium in Petaluma.

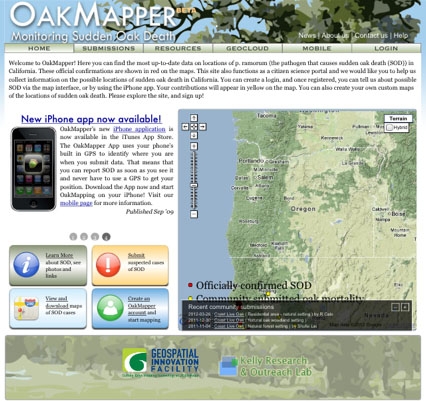

For more information about sudden oak death disease, visit the California Oak Mortality Task Force website at www.suddenoakdeath.org.

Saving the forest by cutting down trees

It's heart wrenching, but forest researchers have found that cutting down bay laurel trees can make a woodland a healthier environment for beloved oaks. The bay laurel trees are carriers of the pathogen Phytophthora ramorum. If the bacteria spreads to oaks, it causes a disease called Sudden Oak Death.

Lisa Kreiger of the San Jose Mercury-News reported that "emergency surgery" is taking place in the Santa Cruz Mountains to extricate bay laurels and give ancient and majestic native California oaks a better chance at survival.

UC Berkeley Cooperative Extension forest pathologist Matteo Garbelotto has observed that removal of bay laurels in a 10- to 20-yard radius of an oak doesn't eliminate the pathogen, but lowers its presence — so a potentially heavy attack is turned into a moderate one, the story said.

"These moderate attacks are less likely to result in an oak infection," Garbelotto was quoted in the article, which also appeared in the Monterey Herald and the Oroville Mercury Register.

Thinning the forest is expected to stem the spread of Sudden Oak Death, but it won't stop it. Although the vast majority of infections come from adjacent trees, the scientists say spores can also travel long distances by wind or creek or by dirt on hiking boots.

Nevertheless, UC Davis forest pathologist David Rizzo told the reporter he believes removing bay laurels is "a great idea.""There are relatively few management options for the disease in wildland areas," Rizzo was quoted. "Stand manipulation is the primary tool we have."

UC Cooperative Extension offers extensive information on Sudden Oak Death. For articles, pictures and links, see the Sudden Oak Death media kit.

California bay laurel leaves and flowers.