Posts Tagged: San Joaquin Valley

New pest infesting almonds and pistachios in the San Joaquin Valley

Crop sanitation will be key to controlling the invasive carpophilus beetle

Growers and pest control advisers (PCAs) should be on the lookout for a new pest called carpophilus beetle (Carpophilus truncatus). This pest was recently found infesting almonds and pistachios in the San Joaquin Valley, and is recognized as one of the top two pests of almond production in Australia. Damage occurs when adults and larvae feed directly on the kernel, causing reductions in both yield and quality.

Populations of carpophilus beetle were first detected in September in almond and pistachio orchards by University of California Cooperative Extension Specialist Houston Wilson of UC Riverside's Department of Entomology. Pest identification was subsequently confirmed by the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

Wilson is now working with Jhalendra Rijal, UC integrated pest management advisor, North San Joaquin Valley; David Haviland, UCCE farm advisor, Kern County; and other UCCE farm advisors to conduct a broader survey of orchards throughout the San Joaquin Valley to determine the extent of the outbreak.

To date, almond or pistachio orchards infested by carpophilus beetle have been confirmed in Stanislaus, Merced, Madera and Kings counties, suggesting that the establishment of this new pest is already widespread. In fact, some specimens from Merced County were from collections that were made in 2022, suggesting that the pest has been present in the San Joaquin Valley for at least a year already.

“It has likely been here for a few years based on the damage we've seen," Rijal said.

This invasive beetle overwinters in remnant nuts (i.e. mummy nuts) that are left in the tree or on the ground following the previous year's harvest. Adults move onto new crop nuts around hull-split, where they deposit their eggs directly onto the nut. The larvae that emerge feed on the developing kernels, leaving the almond kernel packed with a fine powdery mix of nutmeat and frass that is sometimes accompanied by an oval-shaped tunnel.

Carpophilus beetle has been well-established in Australia for over 10 years, where it is considered a key pest of almonds. More recently, the beetle was reported from walnuts in Argentina and Italy as well. Carpophilus truncatus is a close relative to other beetles in the genus Carpophilus, such as the driedfruit beetle (C. hemipterus) that is known primarily as a postharvest pest of figs and raisins in California.

Monitoring for carpophilus beetle is currently limited to direct inspection of hull split nuts for the presence of feeding holes and/or larvae or adult beetles. A new pheromone lure that is being developed in Australia may soon provide a better monitoring tool for growers, PCAs and researchers.

“We're lucky to have colleagues abroad that have already been hammering away at this pest for almost a decade,” said Haviland. “Hopefully we can learn from their experiences and quickly get this new beetle under control.”

The ability to use insecticides to control carpophilus beetle remains unclear. The majority of the beetle's life cycle is spent protected inside the nut, with relatively short windows of opportunity available to attack the adults while they are exposed. The location of the beetles within the nut throughout most of their life cycle also allows them to avoid meaningful levels of biological control.

In the absence of clear chemical or biological control strategies, the most important tool for managing this beetle is crop sanitation.

“Given that this pest overwinters on remnant nuts, similar to navel orangeworm, crop sanitation will be fundamental to controlling it,” Wilson said. “If you needed another reason to clean up and destroy mummy nuts – this is it.”

In Australia, sanitation is currently the primary method for managing this pest. And here in California, new research and extension activities focused on carpophilus beetle are currently in the works.

“It's important that we get on top of this immediately,” said Wilson. “We're already starting to put together a game plan for research and extension in 2024 and beyond.”

If you suspect that you have this beetle in your orchard, please contact your local UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor (https://ucanr.edu/About/Locations/), County Agricultural Commissioner (https://cacasa.org/county/) and/or the CDFA Pest Hotline (https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/plant/reportapest/) at 1-800-491-1899.

No break for kids’ hunger: Partnerships help secure school meal programs

Partnering for California

As the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic hit communities across the U.S. in mid-March 2020, the policy team at UC Agriculture and Natural Resources' Nutrition Policy Institute received an urgent email from a longtime partner in the San Joaquin Valley.

“It was simply entitled 'Help' in the subject line – with multiple exclamation points,” said Christina Hecht, NPI senior policy advisor.

The colleague was writing on behalf of community groups concerned that pandemic-related school closures would jeopardize school meal programs – a nutritional lifeline for children in a predominantly agricultural region with many low-income households.

Hecht immediately contacted a frequent collaborator, Anisha Patel, an associate professor of pediatrics at Stanford University. To help school districts continue those essential meals during the fast-approaching spring holiday, they quickly produced a fact sheet, “Kids' Hunger Doesn't Take a Spring Break,” sharing resources on how districts could use new program flexibility to continue meal distribution.

Then, as the pandemic evolved throughout 2020, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and California Department of Education continued to issue a flurry of waivers and guidance updates. To keep pace, the authors produced three more fact sheets to help districts digest the information and adapt and sustain their school meal programs.

“We tried to make a really user-friendly resource that would help districts sort through everything they needed to do, and easily discover resources for best practices,” Hecht said.

The fact sheet information, paired with advocacy by local partners, encouraged districts to take steps to make more meals more easily accessible to students by taking advantage of USDA waivers: for example, allowing parents to pick up meals without children present, providing multiple meals in one pick-up or implementing bus delivery of meals.

These efforts attracted the attention of the School Nutrition Association, a prominent nonprofit representing more than 50,000 members who provide meals to students across the country. The organization co-branded general versions of the fact sheets and distributed them widely through its website.

Gathering community perspectives on school meals

Those resources represent just one way that lessons from the San Joaquin Valley experience are shaping the national conversation on school nutrition programs. Cultiva La Salud and Dolores Huerta Foundation – health equity and social justice organizations based in Fresno and Bakersfield, respectively – approached the researchers to study ways to boost participation in school meal programs and address food insecurity in their largely Latino communities.

“Working alongside Stanford and NPI is crucial in expanding our capacity and ability to use data and research as a tool to empower parents to advocate for improved health and wellness policies and practices,” said Cecilia Castro, deputy director of Dolores Huerta Foundation, which works in Kern, Fresno and Tulare counties, as well as Antelope Valley in Los Angeles County.

To better understand the “barriers and facilitators” to meal program participation, Hecht, Patel and their collaborators – including student trainees who were eager to learn about community-based participatory research and wanted to help their local communities – sought the perspectives of school district administrators and staff, community groups and parents.

Through the relationships nurtured by Cultiva La Salud and Dolores Huerta Foundation, the researchers convened focus groups of parents with children in six school districts across the San Joaquin Valley.

“We needed to understand better what helped and hindered families from getting the school meals,” Hecht said.

According to Castro, parents have leveraged their feedback to advocate for increased access to school meals, through the use of buses for meal delivery and changes to meal pickup times and locations.

“This engagement has validated the lived experience of our communities,” Castro said. “It has provided an additional strategy for parent leaders to use in efforts to engage decision-makers about ways to improve quality and access to school meals.”

Another key takeaway from these conversations is that the parents are deeply concerned about the content and nutritive value of the meals served to their children.

“We learned that although school meals meet nutrition standards, parents are not aware of this,” Patel said. “Parents also worry about the healthfulness of school meals, noting heavy processing and added sugar. Most compelling was that parents want to provide feedback to improve school meal appeal and healthfulness but have no way to act.”

San Joaquin Valley voices go national

The Nutrition Policy Institute played a crucial role in bringing the parents' perspectives to legislative staff members at the state and federal levels, through the production of four policy briefs that center the voices of San Joaquin Valley residents. In the first, “School Meals: Kids Are Sweeter with Less Sugar,” one parent says: “Children cannot sustain themselves on treats that give pure sugar…They give with the best intentions, but less food would be better, but better quality and healthier.”

“One of the most rewarding parts of all this work has been seeing how meaningful it has been for the parents in the San Joaquin Valley to see their voices getting carried all the way to Washington, D.C. by these policy briefs,” said Hecht. “And it was so meaningful for them that Cultiva La Salud had the briefs translated into Spanish so that the parents could actually read their own words.”

Their voices joined a chorus comprising over 200 organizations who called for universal school meals across California. In June, the state became the first in the nation to adopt a policy, starting in the 2022-2023 school year, to provide free meals for all K through 12 public school students, regardless of family income. Momentum continues to build on the national scale.

The next step for the team is to explore ways to make school meals even more appealing to potential program participants in the Latino communities of San Joaquin Valley. Patel said they will draw on the expertise of Szu-chi Huang, associate professor of marketing in Stanford's Graduate School of Business.

“Using a participatory approach, we will work with parents and school officials to design an intervention focused on communicating the benefits of school meals, and test strategies to improve the appeal of school meals,” Patel explained. “Then we will examine how that intervention affects parents' satisfaction with school meals, students' participation in meals and food insecurity.”

Those insights will be another valuable result of a unique partnership – spurred by a call for help and galvanized by the ongoing health crisis – that continues to benefit families across California.

“Our partnership has been very unusual and very fruitful because we had policy experts, we had research experts and trainees, and then we had the organizations actually working in the community,” Hecht said. “And as we look back on it, it's hard to imagine working that successfully without that kind of partnership.”

Partnerships help secure, improve school meal programs in San Joaquin Valley

Partnering for California

As the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic hit communities across the U.S. in mid-March 2020, the policy team at UC Agriculture and Natural Resources' Nutrition Policy Institute received an urgent email from a longtime partner in the San Joaquin Valley.

“It was simply entitled ‘help' in the subject line – with multiple exclamation points,” said Christina Hecht, NPI senior policy advisor.

The colleague was writing on behalf of community groups concerned that pandemic-related school closures would jeopardize school meal programs – a nutritional lifeline for children in a predominantly agricultural region with many low-income households.

Hecht immediately contacted a frequent collaborator, Dr. Anisha Patel, an associate professor of pediatrics at Stanford University. To help school districts continue those essential meals during the fast-approaching spring holiday, they quickly produced a fact sheet, “Kids' Hunger Doesn't Take a Spring Break,” sharing tips and resources for the districts.

Then, as the pandemic evolved throughout 2020, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and California Department of Education continued to issue a flurry of waivers and guidance updates. To keep pace, the authors produced three more fact sheets to help districts digest the information and adapt and sustain their school meal programs.

“We tried to make a really user-friendly resource that would help districts sort through everything they needed to do, and easily discover resources for best practices,” Hecht said.

Their efforts attracted the attention of the School Nutrition Association, a prominent nonprofit representing more than 50,000 members who provide meals to students across the country. The organization co-branded general versions of the fact sheets and distributed them widely through its website.

Gathering community perspectives on school meals

Those resources represent just one way that lessons from the San Joaquin Valley experience are shaping the national conversation on school nutrition programs. Cultiva La Salud and Dolores Huerta Foundation – health equity and social justice organizations based in Fresno and Bakersfield, respectively – approached the researchers to study ways to boost participation in school meal programs and address food insecurity in their largely Latino communities.

“Working alongside Stanford and NPI is crucial in expanding our capacity and ability to use data and research as a tool to empower parents to advocate for improved health and wellness policies and practices,” said Cecilia Castro, deputy director of Dolores Huerta Foundation, which works in Kern, Fresno and Tulare counties, as well as Antelope Valley in Los Angeles County.

To better understand the “barriers and facilitators” to meal program participation, Hecht, Patel and their collaborators – including student trainees who were eager to learn about community-based participatory research and wanted to help their local communities – sought the perspectives of school district administrators and staff, community groups and parents.

Through the relationships nurtured by Cultiva La Salud and Dolores Huerta Foundation, the researchers convened focus groups of parents with children in six school districts across the San Joaquin Valley.

“We needed to understand better what helped and hindered families from getting the school meals,” Hecht said.

According to Castro, parents have leveraged their feedback to advocate for increased access to school meals, through the use of buses for meal delivery and changes to meal pickup times and locations.

“This engagement has validated the lived experience of our communities,” Castro said. “It has provided an additional strategy for parent leaders to use in efforts to engage decision-makers about ways to improve quality and access to school meals.”

Another key takeaway from these conversations is that the parents are deeply concerned about the content and nutritive value of the meals served to their children.

“We learned that although school meals meet nutrition standards, parents are not aware of this,” Patel said. “Parents also worry about the healthfulness of school meals, noting heavy processing and added sugar. Most compelling was that parents want to provide feedback to improve school meal appeal and healthfulness but have no way to act.”

San Joaquin Valley voices reverberate

The Nutrition Policy Institute played a crucial role in bringing the parents' perspectives to legislative staffs at the state and federal levels, through the production of four policy briefs that center the voices of San Joaquin Valley residents. In the first, “School Meals: Kids Are Sweeter with Less Sugar,” one parent says: “Children cannot sustain themselves on treats that give pure sugar…They give with the best intentions, but less food would be better, but better quality and healthier.”

“One of the most rewarding parts of all this work has been seeing how meaningful it has been for the parents in the San Joaquin Valley to see their voices getting carried all the way to Washington, D.C. by these policy briefs,” said Hecht. “And it was so meaningful for them that Cultiva La Salud had the briefs translated into Spanish so that the parents could actually read their own words.”

Their voices joined a chorus comprising over 200 organizations who called for universal school meals across California. In June, the state became the first in the nation to adopt a policy, starting in the 2022-2023 school year, to provide free meals for all K through 12 public school students, regardless of family income. Momentum continues to build on the national scale.

The next step for the team is to explore ways to make school meals even more appealing to potential program participants in the Latino communities of San Joaquin Valley. Patel said they will draw on the expertise of Szu-chi Huang, associate professor of marketing in Stanford's Graduate School of Business.

“Using a participatory approach, we will work with parents and school officials to design an intervention focused on communicating the benefits of school meals, and test strategies to improve the appeal of school meals,” Patel explained. “Then we will examine how that intervention affects parents' satisfaction with school meals, students' participation in meals and food insecurity.”

Those insights will be another valuable result of a unique partnership – spurred by a call for help and galvanized by the ongoing health crisis – that continues to benefit families across California.

“Our partnership has been very unusual and very fruitful because we had policy experts, we had research experts and trainees, and then we had the organizations actually working in the community,” Hecht said. “And as we look back on it, it's hard to imagine working that successfully without that kind of partnership.”

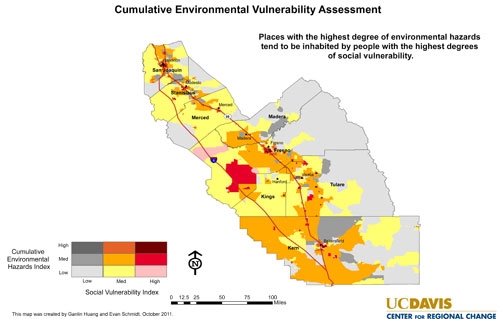

San Joaquin Valley residents face pollution hazards

While California's San Joaquin Valley is home to some of the nation's richest agricultural resources, half of the people who live and work there face elevated levels of air and water pollution coupled with poverty, limited education, language barriers, and racial and ethnic segregation, according to a three-year UC Davis study.

The study, "Land of Risk/Land of Opportunity," also found that residents of the region report more environmental hazards than are currently documented or addressed by state agencies.

"Our conclusion is that immediate and comprehensive action is needed by local, regional and state policymakers to protect the health and well-being of the region's most vulnerable residents," said study leader Jonathan London, director of the UC Davis Center for Regional Change and an assistant professor of human and community development.

The study was conducted in partnership with the San Joaquin Valley Cumulative Health Impact Project, a community-university partnership with environmental health and social justice organizations in the San Joaquin Valley. This work is consistent with UC Davis' goals of seeking knowledge and solutions that sustain and improve quality of life for people in neighboring regions and around the world.

The study uses a new measure developed by scholars on this project, but drawn from methods used by other researchers -- the Cumulative Environmental Vulnerability Assessment -- to identify the locations and populations within the San Joaquin Valley that are at greatest risk.

According to that measure, 51 percent of San Joaquin Valley residents experience high cumulative environmental vulnerability, with more than half of those experiencing acute cumulative vulnerability.

Home to 4 million people, the San Joaquin Valley spans 300 miles through the center of the state. The region is a major transportation artery connecting northern and southern California and contains three of what the U.S. Department of Agriculture designates the nation's top-producing agricultural counties -- Fresno, Kern and Tulare.

The report found:

* The cumulative dangers were not evenly distributed across the region. Some of the communities facing the greatest levels of acute vulnerability include west Fresno, Monterey Park, Kettleman City, Matheny Tract, Earlimart and Wasco.

* Environmental and social vulnerability among at-risk populations persist, despite special attention from regulators and policymakers.

* Those with limited education and English fluency face difficulties advocating on their own behalf.

"With this report, we finally have the data that can lead to collaboration and action," said Kevin Hamilton, deputy chief of programs at Clinica Sierra Vista and a member of the San Joaquin Valley Cumulative Health Impact Project. "It's obvious to all that there are health and other disparities, but there's been a lack of data available to help communities, businesses and government collaborate to take next steps."

The report recommends that analysis of cumulative effects uncovered in the study be integrated into existing policy and planning frameworks in the region, and that special attention be focused on higher-risk areas.

"With one in two residents at elevated risk and one in three at extreme risk, now is the time to solve big problems by looking at the big picture. Without broad discussion and creative solutions, the San Joaquin Valley, especially its children, can't reach its full potential," said Sarah Sharpe, of Fresno Metro Ministry, who coordinates the San Joaquin Valley Cumulative Health Impacts Project.

"This report provides policymakers, government agency leaders, and community activists a tool to measure the cumulative impacts on Valley residents and a road map to prioritizing solutions to these problems."

The study was supported by funding from the Ford Foundation, the UC Davis John Muir Institute of the Environment, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Community Forestry and Environmental Resource Partnerships graduate fellowship.

The report is available at http://regionalchange.ucdavis.edu/projects/current/ceva-sjv.

###

Media contacts:

Edit Ruano, Full Court Press Communications, (510) 550-8176, edit@fcpcommunications.com

Karen Nikos, UC Davis News Service, (530) 752-6101, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu