Posts Tagged: Yellow starthistle

USDA approves release of weevil to control yellow starthistle

The USDA has announced it will allow the release of a weevil (Ceratapion basicorne) in the United States to help control yellow starthistle, an invasive weed found in 40 of the lower 48 states, reported Capital Public Radio. The weevils will initially be released in California.

Ceratapion basicorne is native to Eurasia, the same area where yellow starthistle originated. Yellow starthistle is thought to have been introduced into California from Chile during the Gold Rush. The weed readily took hold in California valleys and foothills, thriving in areas where the soil has been disturbed by animals grazing, road construction and wildland firebreaks. Today, yellow starthistle is a very common sight in vacant lots and fields, along roadsides and trails, in pastures and ranch lands, and in parks, open-space preserves and natural areas.

Capable of growing six feet tall and bearing flowers surrounded by inch-long spines, yellow starthistle reduces land value, prevents access to recreational areas, consumes groundwater and poisons horses.

Brad Hanson, UC Cooperative Extension weed specialist at UC Davis, says yellow starthistle thrives in part because of its prickly spines.

"It's not very palatable to any livestock, especially once it's started to flower . . . . Often times, the other grasses and more palatable plants are grazed and the starthistle persists and is sort of the only thing left,” he said.

Hanson says yellow starthistle can be managed on a small scale with chemicals, but that method just doesn't work with the scale of infestation in the state.

“It's difficult to control economically on the millions and millions of acres of rangelands or non agricultural lands that are sort of minimally managed,” he said.

The USDA's environmental assessment of the weevil found no significant impact of its release, besides helping to control yellow starthistle infestations.

Honey: Nothing short of miraculous

That simple request, prefaced with a term of endearment for good measure, means there's honey on the table.

And well there should be. As the daughter, granddaughter and great-great granddaughter (and beyond) of beekeepers, I grew up with honey on the table. (And on my fingers, face and clothes.)

My favorite then was clover honey from the lush meadows and fields of our 300-acre farm in southwest Washington. My favorite now is Northern California yellow starthistle honey, derived from the blossoms of that highly invasive weed, Centaurea solstitialis, which farmers hate (and rightfully so) and beekeepers love.

“Almost every honey has its own unique flavor-- even when it is the same varietal,” says Amina Harris, director of the UC Davis Honey and Pollination Center. “There are characteristics we learn to look for, but even within that variety, the honey will differ from each area collected. For instance: avocado honey is known for being very dark amber with a flavor reminiscent of molasses, licorice or anise. However, once you start tasting a selection, some will taste like blackstrap molasses and very black licorice. Others will have almost a fruity flavor like dried figs or prunes. Most folks can't tell the difference – and then there are the honey nerds, like me!”

“My favorite all-around honey is one I keep returning to. I love sweet clover from the High Plains with its cinnamon hit —the spicy characteristic is just something I love,” Harris said. “My favorite ‘shock honey' is coriander. Collected near Yuba City, this seed crop gives us a honey that is like walking through a spice bazaar with hints of cardamom, cinnamon, allspice, nutmeg, coriander and — chocolate.”

The UC Davis Honey and Pollination Center, located in the Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science on Old Davis Road, periodically offers courses on the sensory evaluation of honey, as well as honey tastings. Next up: the center will host free honey tastings at its home base during the 105th Annual Campuswide Picnic Day on April 13, and at the California Honey Festival in downtown Woodland on May 4. Another popular honey tasting: California Extension apiculturist Elina Lastro Niño, based in the UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology, hosts a honey tasting at Briggs Hall during the annual Picnic Day.

There's more to honey than meets the eye — or the palate. The Honey and Pollination Center recently hosted a three-day Sensory Evaluation of Honey Certificate Course last October, using “sensory evaluation tools and methods to educate participants in the nuances of varietal honey,” Harris said. Northern California public radio station KQED spotlighted the course on its “Taste This” program.

And we owe it all to honey bees.

Pollination ecologist Stephen Buchmann of the University of Arizona (who received his doctorate in entomology from UC Davis, studying with native pollinator specialist Robbin Thorp), writes in his book, Honey Bees: Letters from the Hive, that each worker bee “may make four to ten or so flights from the nest each day, visiting hundreds or many thousands of flowers to collect nectar and pollen. During her lifetime, a worker bee may flown 35,000 to 55,000 miles collecting food for her and her nest mates. One pound of honey stored in the comb can represent 200,000 miles of combined bee flights and nectar from as many as five million flowers.”

Take a 16-ounce jar of honey at the supermarket. That represents “the efforts of tens of thousands of bees flying a total of 112,000 miles to forage nectar from about 4.5 million flowers,” writes Buchmann.

Of course, we primarily appreciate honey bees for their pollination services (one-third of the food we eat is pollinated by bees) but honey is more than just an after thought.

It's been described as “liquid gold,” “the nectar of the gods” and “the soul of a field of flowers.” Frankly, it's nothing short of miraculous.

And well it should be.

A honey bee sips honey from honeycomb. (Photo by Kathy Keatley Garvey)

A honey bee sips nectar from a lavender blossom. (Photo by Kathy Keatley Garvey)

California budget cuts impact yellow starthistle control

The project was funded by the state Department of Food and Agriculture as part of its weed control budget totaling $2.7 million in 2011. That money was cut from the 2011-2012 state budget cycle. Local and federal grants that kept the program going will run out next month. A $314,000 grant from the Sierra Nevada Conservancy was denied because the group failed to meet the application requirements, the article said.

These developments may give starthistle a bigger hold on California wildland. The roots of the nuisance weed grow as much as six feet deep to find moisture.

"It would be as if these areas are experiencing drought because of the amount of water it uses," said Joe DiTomaso, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences. DiTomaso is a leading expert on starthistle.

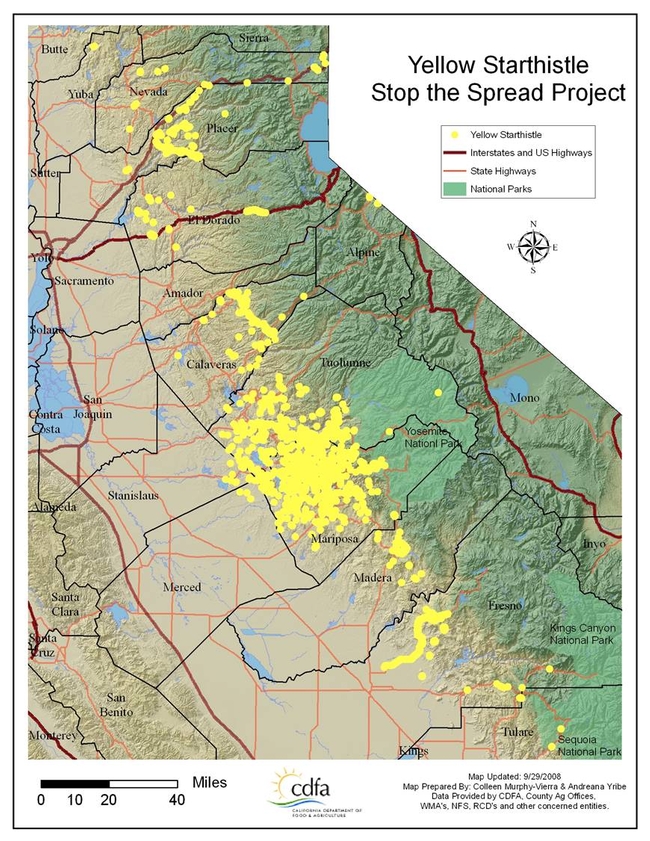

The Leading Edge Project started about a decade ago with a mapping effort to find out just how much of the state was infested with starthistle, and where it was spreading, said Wendy West, the project's coordinator and a University of California Cooperative Extension program representative based in Placerville.

"It felt like such a losing battle that we really needed to prioritize what we could do and how we could be successful," West said.

"I've personally pulled plants at 7,000 feet in Alpine County," West said. "It may not move quite as fast, but yellow star thistle is a really good example of a plant that can adapt to new locations easily."

Time to plan your yellow starthistle weed attack

Weeds, weeds, weeds! Have you noticed? This has been a banner year for weeds. Puncturevine where I’ve never seen it before. Garden soil covered with common purslane (at least it’s good in salads). And solid stands of yellow starthistle everywhere!

What can be done? First of all, identify your weeds. Different weeds require different treatments. Is it an annual or perennial? Does it propagate by wind-blown seeds or by runners? The University of California Integrated Pest Management website, has weed-identification guides that are fun and easy to use. The website also offers treatment guidelines.

In the California foothills, yellow starthistle (YST) is perhaps the most common weed of concern. It impacts much of our open space - agricultural and rangeland - and intrudes into our neighborhood landscapes. Yellow starthistle currently infests more than 15 million acres of land in California. Not only does it prevent recreational use, like walking or hiking, but it chokes out native grasses and wildflowers. It is also poisonous to horses, causing a neurological disorder called "chewing disease” which can be fatal once symptoms develop.

That said, yellow starthistle can be hand-pulled at any time in its lifespan. In its present dry and spiny stage, pulling the weeds can inflict pain, so be sure to wear gloves. Double-bag the plants and burn them later in the fall.

There is a fairly new herbicide (2009) on the market from Monterey Chemical called Star Thistle Killer.

Local pest control companies are also available to provide a one-time herbicide application for yellow starthistle. For more information, go to the Central Sierra Cooperative Extension website or call the Yellow Starthistle Leading Edge Project in the UC Cooperative Extension office at (530) 621-5533 or (209) 533-6993.

Information adapted from the University of California Integrated Pest Management Program and from “Yellow Starthistle: Brief Homeowner Information Sheet” by John E. Otto, Amador County Master Gardener.

Also see the following video on yellow starthistle control.

YST Homeowner Handout

RebeccaYST

Goats can help with yellow starthistle control

Yellow starthistle is thought to have been introduced into California from Chile during the Gold Rush. The weed readily took hold in California valleys and foothills, thriving in areas where the soil has been disturbed by animals grazing, road construction and wildland firebreaks. Today, yellow starthistle is a very common sight in vacant lots and fields, along roadsides and trails, in pastures and ranch lands, and in parks, open-space preserves and natural areas.

Capable of growing six feet tall and bearing flowers surrounded by inch-long spines, yellow starthistle reduces land value, prevents access to recreational areas, consumes groundwater and poisons horses. (Yellow starthistle isn't all bad. Beekeepers have found that it can provide an important late-season food source for bees.)

That's where goats can come in. Goats will eat yellow starthistle at all phases of growth, including the mature, spiny stage, when it is not palatable to other browsers and grazers.

"When goats eat yellow starthistle, they open up the canopy and allow sunlight to hit the ground," said Roger Ingram, UC Cooperative Extension natural resources advisor. "That allows other, more beneficial seeds to come up and grow. If you can get other plants growing in there, the competition will choke out yellow starthistle."

Landowners can raise goats themselves and direct them to areas of starthistle infestation with portable fencing, or they can lease the animals exclusively for vegetation control. More information on yellow starthistle management is available from the UC Integrated Pest Management Program.

View the video below for more information on goats' browsing preferences.

Read a transcript of the video.

GoatsYST