Posts Tagged: wetlands

Caltrans to cooperate with UCCE on long-term rangeland practices study

A settlement between Caltrans and the California Farm Bureau Federation, which resulted in CFBF dismissing a lawsuit against Caltrans about the Willits Bypass Project, includes a long-term wetlands study by UC Davis and UC Cooperative Extension researchers, according to Caltrans and farm bureau press releases issued last week.

Caltrans is building a bypass along U.S. Route 101 around the community of Willits. The project will relieve congestion, reduce delays, and improve safety for traffic and pedestrians, Caltrans said. CFBF filed the lawsuit because of concern about how the project would impact farmland in the Little Lake Valley.

"Specifically, Farm Bureau was concerned about the amount of farmland the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers mitigation strategy required to be removed from production in order to mitigate for wetlands affected by the bypass," the CFBF press release said.

According to the terms of the agreement noted in both press releases, Caltrans will cooperate with UC Davis and UCCE to study how grazing management contributes to enhanced wetland function.

The study will look at land owned by the state — where grazing is required — and federally owned land — where grazing is prohibited — and consider how to optimize grazing productivity while achieving the desired wetlands enhancements. The research will provide an opportunity to study how natural resources can be preserved and land utilized for both grazing and wetlands.

UC researchers will study how to optimize grazing productivity while achieving desired wetlands enhancements.

Biofilms: Friends or foes?

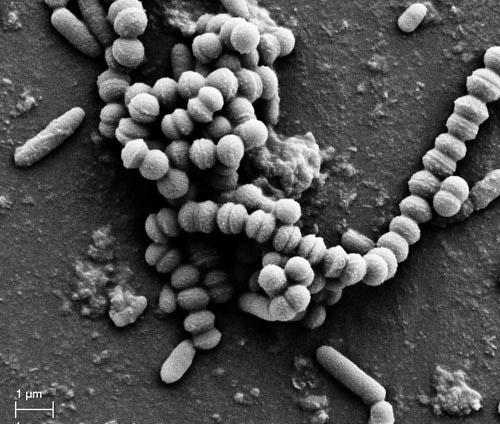

"Biofilms" surround us. They pervade our environment and our bodies. They form the dental plaque on our teeth and establish the chronic infections in our childrens' ear canals. They can spread on the watery surface of a contact lens.

Biofilms are now thought to be involved in 80 percent of human microbial infections, and are likely responsible for the resistance of chronic infections to antibiotics. Biofilms even form around "extremophiles" – such as the ancient blue-green cyanobacteria that thrive in extreme environments like the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park and the lake crusts of Antarctica. These microorganisms with fossil records going back 3.5 billion years also clog water pipes and create the slimy film on rocks in a pond.

A “biofilm” is a protective environment created by a microbial population. When microbes such as bacteria sense a “quorum” of their kind nearby, they begin to modify their genetic instructions to produce polysaccharides. The result is a sticky matrix that enables them to adhere to each other, and to surfaces.

But there is more to this story. Biofilms can also be employed for our benefit. Many sewage treatment plants include a stage where wastewater passes over biofilms, which “filter” — that is, extract and digest — organic compounds. Biofilms are integral to our current engineering processes for wastewater treatment.

Similarly, they play an essential role in constructed wetlands (CW), the artificial systems that approximate natural wetlands and that are used to treat wastewater or stormwater runoff. Most constructed wetlands are planted with hydrophilic (water loving) plants, while others are simply a gravel “filter” media. Both involve biofilms at the water-solid interfaces.

Recent research has now shown that planted CW systems — with their associated biofilms — are significantly more effective in the first weeks and months of treating agricultural processing wastewater.

In greenhouse trials, the planted system removed approximately 80 percent of organic-loading oxygen demand from sugarcane process wastewater after only three weeks of plant growth. The unplanted system removed about 30 percent less.

“Every constructed wetland system has a 'ripening period' during which the biofilm is forming," said Mark Grismer, UC Davis biological engineer. "Ripening means the time it takes for bacteria or other microorganisms to become established and functioning with respect to organics removal. Results indicate this ripening period is shorter in planted CW systems, and can be as short as three weeks if fast-growing aquatic plants are involved in the constructed wetland. In systems without plants, it can continue for two to three years.”

“Plant roots provide the structure needed for biofilm bacteria to process wastewater. Also, because the surface area of plant roots is far greater than that of the sand, gravel, or rock substrate alone, and because roots have the ability to partially oxygenate their surfaces, they can support thicker and perhaps more robust biofilms,” he said.

Studies like this one are providing the field data needed to strengthen efforts to clean up agricultural processing wastewaters.

To read the complete article, go to the April-June edition of California Agriculture journal.