- Author: Jeffery A. Dahlberg

Two of Kearney's researchers, Jeff Dahlberg and Khaled Bali joined Dan Putnam of UC Davis in a trip to Pakistan to talk with Pakistani researchers, academics, and farmers about forage production. Pakistan has reached out to their expertise to help understand improved forage practices that will help Pakistan meet its dairy and meat needs in the future. The three UC researchers gave presentations in Faisalabad and Multan at the Agricultural Universities. Dr. Putnam gave presentations on alfalfa, Dr. Dahlberg on sorghum as a forage, and Dr. Bali on irrigation and evapotranspiration. Their Pakistani hosts were very gracious and appreciative of their efforts. While there, they also participated in a fabulous tradition at the Ag Universities, planting of a tree in each of their names. The Kearney and Davis researchers look forward to strengthening these new relationships between Pakistani scientists and those of UC and ANR.

- Author: Jeannette E. Warnert

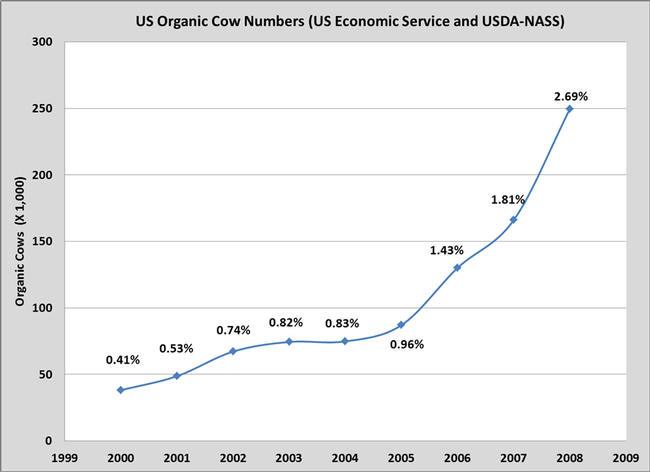

Among the conditions necessary for a cow to produce organic milk, she must eat only organic feed or browse on organic pasture for at least the previous 36 months. However, dairy producers have found that producing or sourcing organic feed – which must be grown with no synthetic fertilizers, insecticides or herbicides – is challenging. Recently organic alfalfa made up nearly 1.4 percent of U.S. alfalfa hay production, up from .5 percent in the early 2000s.

Dan Putnam, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Plant Sciences at UC Davis, an alfalfa expert, said one key obstacle for organic alfalfa producers is weed management. Putnam put together a team of alfalfa hay experts to conduct an alfalfa weed management trial at the UC Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center, where 10 acres are set aside to research organic production.

In 2011, Putnam; Carol Frate, UCCE advisor in Tulare County; and Shannon Mueller, UCCE advisor in Fresno County, experimented with timing seeding and early clipping to manage organic alfalfa in a weedy field.

“Alfalfa can be planted from early September all the way through the fall and winter to early spring, depending on weather patterns,” Putnam said. “Many farmers plant in late November and wait for rain to bring the crop up. Other options are irrigating the crop up in early fall or waiting till early or late spring to plant the crop. All of these strategies have implications for weed management.”

The late November planting is quite common since, compared to a September planting, it saves farmers the trouble of putting out sprinklers. However, late fall plantings failed in this experiment.

“We had a lot of weed intrusion at that point as well as cold conditions for alfalfa growth, so the stands were poor,” Putnam said.

The earlier planting also had weed intrusion, but the researchers clipped the field when the alfalfa was 10 to 12 inches high in early spring. The clipping cut back weeds that were overtopping the alfalfa, giving an advantage to the vigorous young alfalfa seedlings.

An early spring planting after tillage to destroy weeds also resulted in a good stand, but some production was lost in the first year compared with early fall plantings.

“Many growers are starting to realize that early fall (September/October) is a better time to start their alfalfa crops,” Putnam said. “With organic growers, it is even more important to pay attention to time of seeding because they have so few weed control options.”

While this research is conducted on organic alfalfa, Putnam said the results are also applicable to conventional alfalfa production, which represents more than 98 percent of California's total alfalfa crop.

“Timing has a profound effect on the first-year yield and health of the crop and its ability to compete with weeds,” he said.

Putnam, Mueller and Frate will share more information about the organic alfalfa trial during a field day at Kearney, 9240 S. Riverband Ave., Parlier, from 8 a.m. to 12 noon Sept. 5. The field day will feature the organic production trials, alfalfa variety trials, sorghum silage and nitrogen trials, and optimizing small grain yields. Other topics will be alfalfa pest management, irrigation and stand establishment.

- Author: Jeannette E. Warnert

Dahlberg introduced San Joaquin Valley farmers to a new sorghum variety trial during the Alfalfa Field Day Sept. 8. The trial, which compares 80 varieties of forage sorghum, is also being conducted at the UC West Side Research and Extension Center in Five Points, Calif. At Kearney, the 10- to 12-foot-high plants were grown in 84 days with just 8 inches of irrigation water.

"I'm going to push this to be a sorghum state," said Dahlberg, who came to California in January from Texas, where he was director of research for the United Sorghum Checkoff Board. "I'm not suggesting you take out all your corn forage, but experiment with this a little. There is no reason you shouldn't grow forage sorghum."

Dahlberg said the crop could be useful in rotation with traditional California crops, like cotton and corn.

"There are lots of acres on the West Side that I think could benefit with sorghum rotation," he said.

Alfalfa trials

Alfalfa Field Day participants also viewed alfalfa growing at Kearney as part of an extensive, statewide alfalfa variety trial. Similar plots are being maintained at UC's Intermountain Research and Extension Center, about two miles south of the Oregon border, at the Desert Research and Extension Center, about 10 miles north of the Mexican border, and at several locations in between.

UC Cooperative Extension alfalfa specialist Dr. Dan Putnam said the data gathered in these trials are provided to growers on the UC Alfalfa and Forage website to help them select a variety to grow, a decision Putnam admonished farmers not to take lightly.

"You are 'stuck' with your variety decision for many years," Putnam said. "So why not take a little care in choosing your variety?"

Putnam also described an alfalfa trial at Kearney where a Roundup Ready cultivar is growing across the road from a conventional crop. During the first year of the study, tests have shown that there has been no discernible gene flow between the two fields.

Alfalfa grown for seed requires honey bee pollination and has different isolation requirements than hay, he said. A three-mile buffer must be maintained for production of Roundup Ready seed and a five-mile buffer is required for seed grown for markets sensitive to a genetically-engineered trait. However, alfalfa hay crops can be grown in close proximity with very low risk of contamination if growers follow a few simple steps.

Putnam believes that non-GMO farmers can coexist with conventional farmers by using some of the same good-neighbor farming accords that have long been common in agriculture.

"There is a human factor involved," Putnam said. "Neighbors have to get along and respect each others' points of view."

One way for farmers and buyers to be certain a non-GMO crop doesn't have the Roundup Ready gene is with a simple, commercially available test that can be used in the field or on baled hay, shown below.