- Author: Daniel H. Putnam

- Author: Rachael Freeman Long

JUST HOW DRY IS IT?

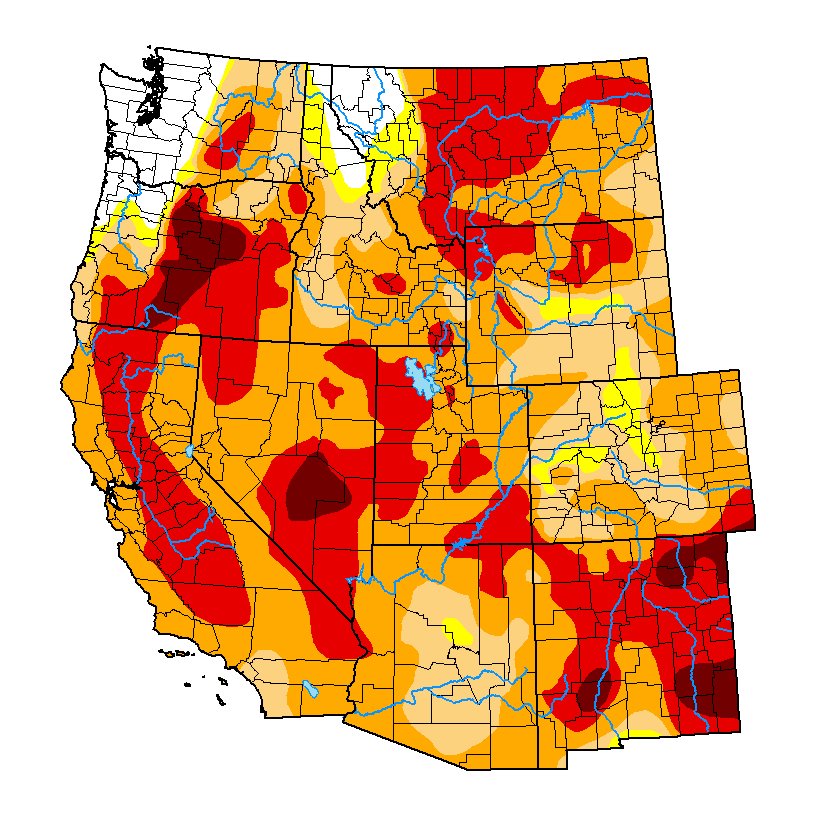

It really doesn't look good out there for many western alfalfa growers. Most parts of the West are currently under 'severe, extreme, or exceptional' drought.

One would think that NOAA and USDA would run out of superlatives! (how about 'excruciating'?).

Figure 1. Drought status, April 28, 2022 (Drought Monitor, USDA, NOAA).

Normally our wettest months, the first four months of 2022 were some of the driest on record for California, which does not bode well alfalfa and other crops. Many of our alfalfa fields have dried out well before the first cutting.

IMPACTS ON ALFALFA

What does this mean for alfalfa, which is a large acreage crop in the West, often the top ranking by acreage? Since most (e.g. >95%) of the West's alfalfa is irrigated, this presents a major challenge for alfalfa growers. According to the Economic Research Service (ERS), nearly 50% of US Alfalfa was under drought in late 2021, the largest in a decade (Figure 1). Drought conditions have continued in early 2022 for most regions.

This, along with greatly reduced acreage, is an explanation for the record high alfalfa hay prices in 2022 (Table 1), with premium hay well over $400/ton ($150/ton more than last year- The Hoyt Report, 2022). So the need for the crop has not diminished, but our ability to produce alfalfa hay has been greatly curtailed.

Figure 2. Impacts of Drought on Alfalfa over a 10-year period (USDA-ERS, 2021)

TABLE 1. Hay Prices ($/ton) Delivered to California Dairies (Tulare/Hanford), Hoyt Report, April 22, 2022)

| Quality Category | April 2022 | April 2021 |

| Supreme Quality | $435-455 | $285-310 |

| Premium Quality | $410-425 | $270-285 |

| Good Quality | $395-410 | $255-260 |

| Fair Quality | $380 | $235 |

ALFALFA-THE BEST CROP FOR A DROUGHT

In a previous blog, titled ‘Why Alfalfa is the best crop to Have in a Drought'), we describe the reasons that alfalfa is actually suited to periodic droughts. While this may seem counter intuitive, since fully-irrigated alfalfa has a high water footprint, alfalfa has a high degree of resilience for persisting in drought conditions. This is due to its deep roots, periodic harvests, and it's ability to obtain water from deep in the soil. It originated in the near-East regions of long dry summers and wet winters, and generally survives drought successfully, while remaining economically viable. Alfalfa has a series of biological characteristics that enable it to be an important component of drought resilience in agriculture (see Putnam, et al., 2021, The Importance of Alfalfa in a Water Uncertain Future). Importantly, alfalfa can be partially irrigated during the season to obtain partial yields to sustain farms and dairy production.

WHAT ARE THE OPTIONS UNDER DROUGHT?

A fully-irrigated alfalfa crop requires a certain amount of water for full production (Table 2). At Davis, California, the yearly demand is about 40", but the amount needed is closer to 50-54 inches in the southern San Joaquin Valley due to the longer season and higher heat. Lower amounts are required in the shorter season mountain valleys and higher amounts in the Low Desert (Table 2). Remember, alfalfa yield is directly related to the ET of the crop, with means that sufficient water results in highest yields. Yield increases in a straight-line manner as seasonal ET increases. Insufficient soil moisture causes yield losses.

Table 2. Seasonal ET of fully-irrigated alfalfa for various locations in California

| Site | Seasonal ET (inches) |

|

Imperial Valley

|

61

|

|

Central Valley

|

54

|

|

Scott Valley

|

35

|

|

Tulelake

|

38

|

What are the options when there simply isn't enough water?

1. TRIAGE-Move water to only those best fields. If your plumbing allows, choose only the best alfalfa fields for watering, allowing the worst fields to go fallow this year. Many growers do this, moving water to only the highest return crops. However, alfalfa is an excellent economic option with such high prices, and production of good stands of alfalfa even with expensive water, is likely to be profitable in a year like this (when demand exceeds supply).

2. STARVATION DIET--Water the crop less at each cutting than normal. In this case, for example, if a crop requires about 1/4" to 1/3" per day (typical during summer), a fully watered demand would range from 7 inches to 9.25 inches per month. A 'deficit irrigation strategy' in this case would apply (for example) 50-60% of this amount per week or month.

3. 'COLD TURKEY' SUMMER DRY-DOWNS--This would require FULL irrigation during the first several growth periods in the spring: fully watered early to meet ET, followed by summer sudden cut off of irrigation water when necessary. The field will go dormant and there will be no further yield after irrigation ceases, but the stand will generally recover once the field gets watered again or rains return.

CONCLUSIONS

Under most conditions we would recommend to choose only the best fields to water, and water them fully during the early part of the year. We do NOT recommend 'starvation diet' strategies (#2). Make sure that the soil profile is as well-supplied with water as possible early in the season (full profile). Then, if necessary, cut down on irrigation in the late part of the season. Why is this the case?

1.The highest quality, highest yielding cuttings are in the earliest stages (until July). Yields are lower in the later cuttings even if fully watered, so the impact on yield is less when those late cuts are not watered.

2. 60-70% of alfalfa yields are achieved by early- mid-July, and its important to maximize those yields and produce some forage during the year.

3. Alfalfa often enters a 'summer dormancy' when not watered, and can then recover in the winter/spring (Figures 5 and 6).

4. 'Starvation diet' or failing to fully water a cutting results in much lower yields, stressed crops, and early flowering.

5. Filling the soil water profile early allows the crop to sustain yields even in mid-summer, since it is difficult to 'catch up' with water demand during the long hot spells of summer. Once you're behind in water, you can never catch up until winter rains come.

6. It's better to forgo several late cuttings, saving money on harvest and pest management costs.

FURTHER RECOMMENDATIONS

Extending cutting schedules during the early growth periods to maximize yields early: Take a look at Table 1 - the price for even 'good' quality hay would likely justify obtaining (say) another 1/2 ton of production by extending your cutting schedule by a week or 10 days!

Testing for Nutrient Limitations. Drought stressed roots are less able to obtain nutrients from the soil. Test to make sure that P, K, S, and some micronutrients (e.g. Mo) are not limiting to growth. Although fertilizer prices are high, it's important to maximize yields to take advantage of scarce water. Many growers go years without soil or plant testing - time to change that practice.

Growers face unhappy choices when it comes to coping with drought. However, alfalfa is a highly resilient crop that can be partially irrigated to produce from 50% to 90% of full yields under drought, depending upon how it's done.

Figure 3. UCCE Advisor Rachael Long (left) and grower Ron Tadlock consult on one of his drought stressed fields in Yolo County, CA, April, 2022. The soil has become very dry. Since at least 3 weeks remain before the first harvest, he elected to water the field to provide water for the upcoming hot periods. It's important to 'fill the deep profile' for alfalfa on good soils to maximize early yields, and provide residual moisture for additional cuttings.

Figure 4. Alfalfa growing on residual moisture in late June, 2021, Tulelake, CA. Only 6" of rain occurred earlier that year. Note: this is an unusual result due to the unique organic soil type with high water holding capacity, but illustrates the value of deep rooting systems, and alfalfa's ability to obtain deep moisture.

Figure 5. Drought-affected alfalfa field exhibiting summer dormancy in late August, 2014 during a historical 5 year drought (Sacramento Valley, CA).

|

Figure 6. Alfalfa field fully recovered in January, 2015 (same field as in Figure 5) from a 3 month drought imposed June-October in 2014, Sacramento Valley, CA.