Calag Archive

Calag Archive

Soil nitrate testing supports nitrogen management in irrigated annual crops

Publication Information

California Agriculture 71(2):90-95. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.2016a0027

Published online December 15, 2016

Abstract

Soil nitrate (NO3−) tests are an integral part of nutrient management in annual crops. They help growers make field-specific nitrogen (N) fertilization decisions, use N more efficiently and, if necessary, comply with California's Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program, which requires an N management plan and an estimate of soil NO3− from most growers. As NO3− is easily leached into deeper soil layers and groundwater by rain and excess irrigation water, precipitation and irrigation schedules need to be taken into account when sampling soil and interpreting test results. We reviewed current knowledge on best practices for taking and using soil NO3− tests in California irrigated annual crops, including how sampling for soil NO3− differs from sampling for other nutrients, how tests performed at different times of the year are interpreted and some of the special challenges associated with NO3− testing in organic systems.

Full text

Growers in California face increasing pressure to use nitrogen (N) fertilizers efficiently to reduce the risk of nitrate (NO3−) leaching to groundwater, which makes soil NO3− testing an important component of N management. However, soil NO3− sampling and interpretation are not straightforward. The soil NO3− pool is subject to additions and losses throughout the year, and a soil NO3− test gives a snapshot only of the NO3− present when the sample is taken.

In most agricultural soils, NO3− is the major inorganic form of N. Because of this, and its mobility in soil, it is the form primarily taken up by plants in fertilized agricultural systems, although plants also take up ammonium (NH4) and to a lesser degree small organic molecules (Schimel and Bennett 2004). The soil NO3− pool may include N left over from the previous crop, N from recent fertilizer applications, N released from organic materials such as organic matter, manure or crop residues in a process known as mineralization, and N from irrigation water (Huggins and Pan 1993).

If winter rainfall is insufficient to leach it below the rooting zone, soil NO3− can accumulate and NO3− may be high in spring. However, NO3− can also be quickly leached with excess irrigation or heavy rainfall (Magdoff 1991; Spellman et al. 1996). Soil NO3− concentrations in spring can therefore be extremely variable. In a recent study of drip-irrigated tomato fields in the Central Valley, Lazcano et al. (2015) reported NO3− concentrations in the top 10 inches ranging from 20 to well above 200 pounds per acre.

Preplant soil samples should be taken in spring, as closely as possible to a planned fertilizer application and after any pre-irrigation.

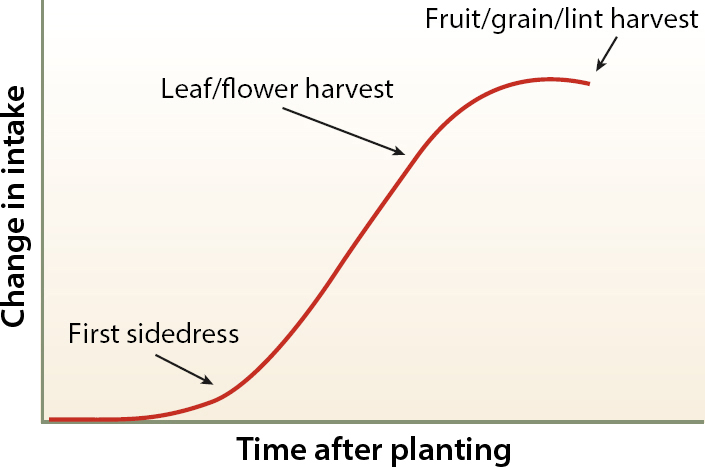

Irrigated agriculture presents both challenges and opportunities for efficient N management. A major advantage of irrigated agriculture is that water volume can be controlled to a much greater extent than in rain-fed systems. Furthermore, when irrigation systems have good uniformity, N can be applied with the irrigation water at any time during the season, rather than in one large dose early in the season (as with rain-fed systems). This enables growers to avoid excessive soil NO3− during early crop growth when the plant demand is low and the leaching risk is greater (fig. 1). In a well-managed irrigated system, both water and N applications are fit to crop needs to maximize N use efficiency. However, because excess irrigation can result in considerable NO3− leaching losses, irrigation management needs to be taken into account when obtaining samples and interpreting soil NO3− test results.

We reviewed methods for obtaining and interpreting soil NO3− samples that are appropriate for irrigated annual cropping systems in California. Similar principles apply to perennial crops, but we focused on annual crops as tissue analysis, not soil analysis, is the common N management tool for perennial crops.

Soil sampling

Soil samples for NO3− analysis must be representative of the field or block from which they are taken. A test result from a nonrepresentative sample has little value. In a paper recently published in this journal, Geisseler and Miyao (2016) discussed strategies to obtain representative soil samples for phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). These sampling principles also apply to NO3− testing. However, there are several aspects growers and crop advisers need to be aware of when taking soil NO3− samples from irrigated fields:

-

The NO3− concentration in the soil profile is affected by many factors related to weather and crop management. Results from the same field can differ considerably from one year to the next. For this reason, soil NO3− samples need to be taken every year.

-

A heavy rainfall or irrigation right after soil samples are taken can reduce the NO3− present in the sampled layer considerably, making the test meaningless. Therefore, soil NO3− samples need to be taken as close as possible to planned fertilizer applications.

-

Due to the mobility of NO3−, an accurate measure of its NO3− availability requires a sample of the main rooting zone. For vegetables, this is normally the top foot; for field crops, samples should be taken to at least 2 feet.

-

The samples need to be kept cool and sent to the analytical lab quickly. If this is not possible, they should be quickly air-dried. This is important because N mineralization from organic sources continues in moist and warm samples, resulting in an overestimation of the NO3− present in the soil profile.

If the samples cannot be kept cool and sent to the lab immediately, they should be quickly air-dried in a thin layer.

Soil nitrate quick tests

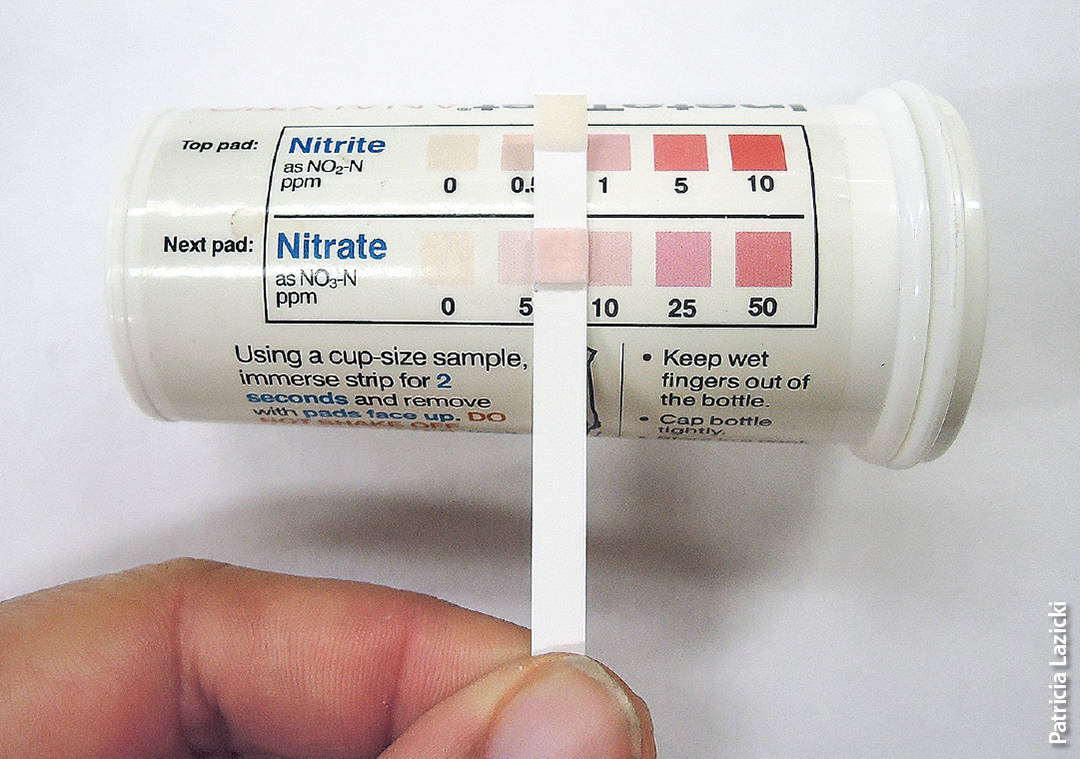

Soil samples are normally analyzed by commercial labs. However, for routine field monitoring like that described in this paper, an on-farm quick test for NO3− has been developed, using inexpensive test strips. This quick test is especially useful for in-season testing, when the lag time between taking the sample and getting a result back from the lab is too long. Several studies with vegetables in California have demonstrated that quick tests are well correlated with lab analyses across the usual range of NO3− concentrations encountered (Breschini and Hartz 2002; Hartz et al. 1994; Hartz et al. 2000). They are accurate enough to be used to reliably identify fields that do not need sidedress N (Breschini and Hartz 2002). However, they are not as accurate as lab analyses, and it is recommended that growers periodically send in soil samples to a lab as well (Hartz et al. 1994).

Soil NO3− quick tests are an alternative to lab analyses when the results are needed quickly. However, they are not as accurate.

Preplant nitrate test (PPNT)

A preplant nitrate test (PPNT) is used to adjust the N application rate to site-specific conditions when a large proportion of the seasonal N requirements must be applied preplant. The soil sample is generally taken from the major rooting depth of the following crop. Since soil NO3− is directly available to plants and behaves like fertilizer NO3− (Vanotti and Bundy 1994), the fertilizer N application rate may be adjusted according to the NO3− present in the soil.

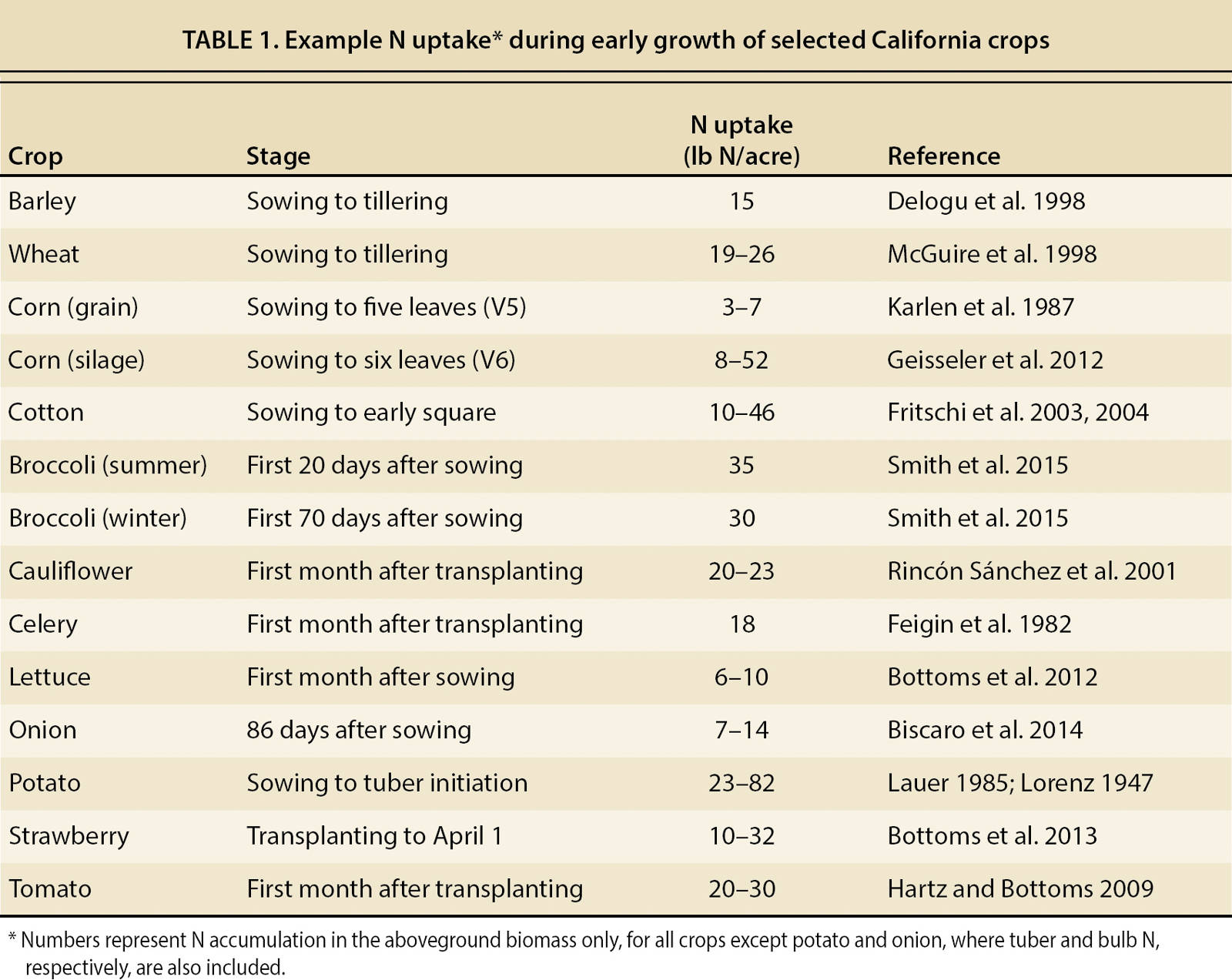

For most crops, a preplant nitrate-N (NO3−-N) concentration of 15 to 20 parts per million (ppm) indicates that sufficient soil N is present to meet N demand during the early growth stages (table 1). In mineral soils, ppm NO3−-N is generally converted to pounds per acre per foot of soil using conversion factors of 3 to 4, such that a concentration of 20 ppm corresponds to 60 to 80 pounds N per acre per foot of soil (54 to 71 kilograms per hectare in the top 30 centimeters). In soils with high organic matter concentration, lower factors should be used due to the lower bulk density.

In many crops, a small starter fertilizer application may still be beneficial for early crop development, even when soil NO3− exceeds the 20 ppm threshold (Stone 2000). While starter fertilizer is applied in a concentrated band near the roots of the seedlings, soil NO3− is more evenly distributed across the surface of the field. As roots of seedlings explore a limited soil volume early in the season, only a proportion of the soil NO3− is available at early growth stages. In addition, starter fertilizer generally contains N in the form of NH4, which has been found to improve P uptake (Grunes 1959).

Adjusting fertilizer N recommendations based on preplant soil NO3− concentrations is a widespread practice in Europe and North America (Olfs et al. 2005). However, the usefulness of the PPNT in irrigated agriculture highly depends on irrigation type and management (Bilbao et al. 2004; Cela et al. 2013), as it may be several weeks before NO3− present in the soil at planting is taken up by growing plants (fig. 1; table 1). During this time, when plant water and N uptake are negligible and soils may be irrigated frequently to ensure crop germination and establishment, NO3− is at risk of being leached below the root zone. Test results may overestimate plant-available NO3−-N if rainfall or irrigation water leaches NO3−-N to deeper soil layers after the samples have been taken. If fields are preirrigated, preplant soil samples should be taken after the irrigation (Wyland et al. 1996).

In-season soil nitrate tests

Taking an early season NO3− sample in processing tomatoes, just prior to the period of rapid N uptake.

When most N can be applied during the growing season, it is preferable to apply a small amount of N as a starter and then take a NO3− test just prior to the sidedress application to determine the need for N fertilizer. Nitrogen uptake is generally highest during the second half of the vegetative growth phase (fig. 1). By taking the NO3− test just prior to when N uptake is high and when the root system is already well developed, the risk of NO3− leaching after the samples have been taken is greatly reduced. Due to the later date, N mineralized between planting and sidedressing is also included in the sample, making it a more accurate measure of crop-available soil N than a preplant test.

In systems where more than one sidedress application is not practical, the test value can be used to adjust the sidedress N application rate, as described for the PPNT.

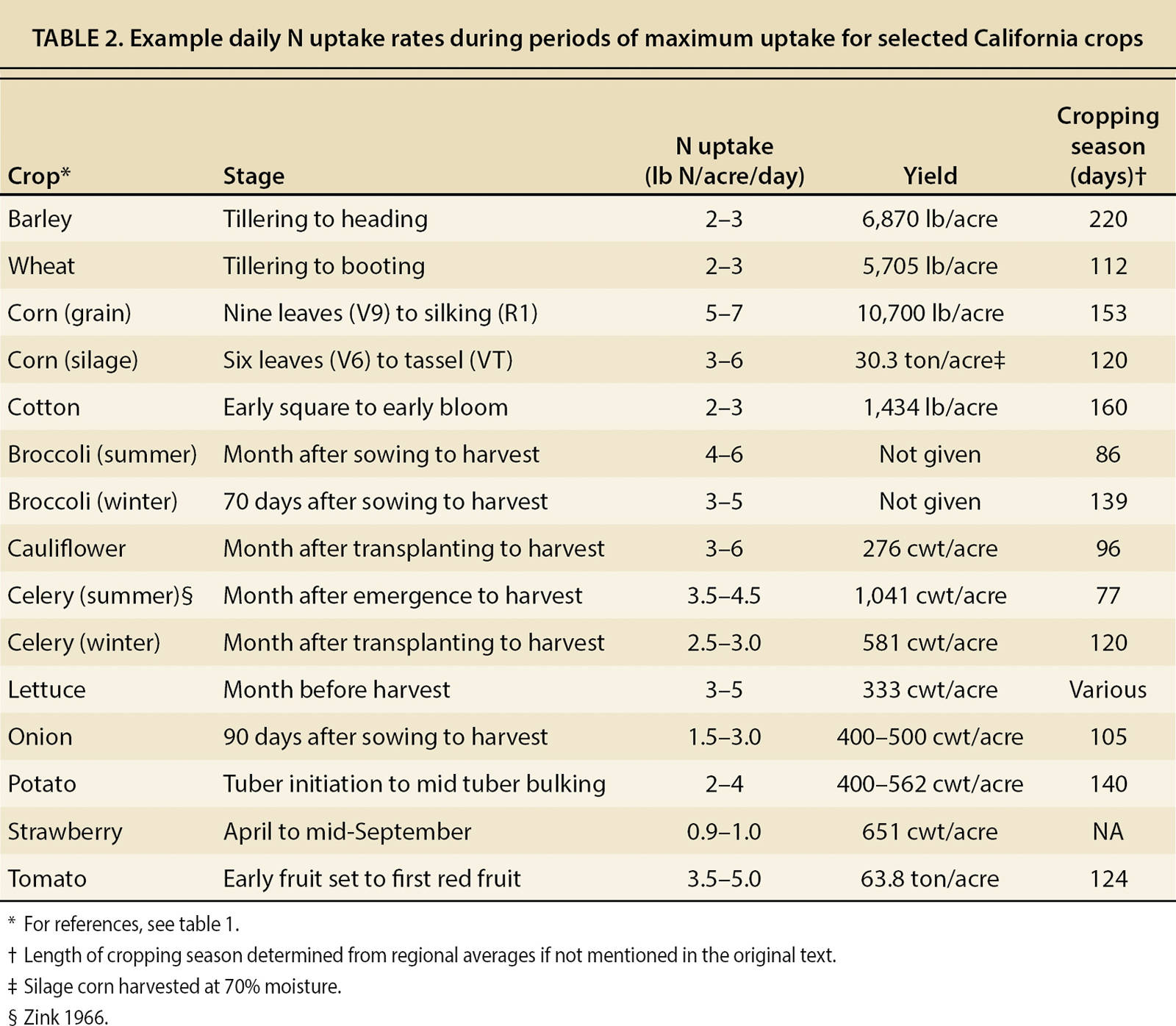

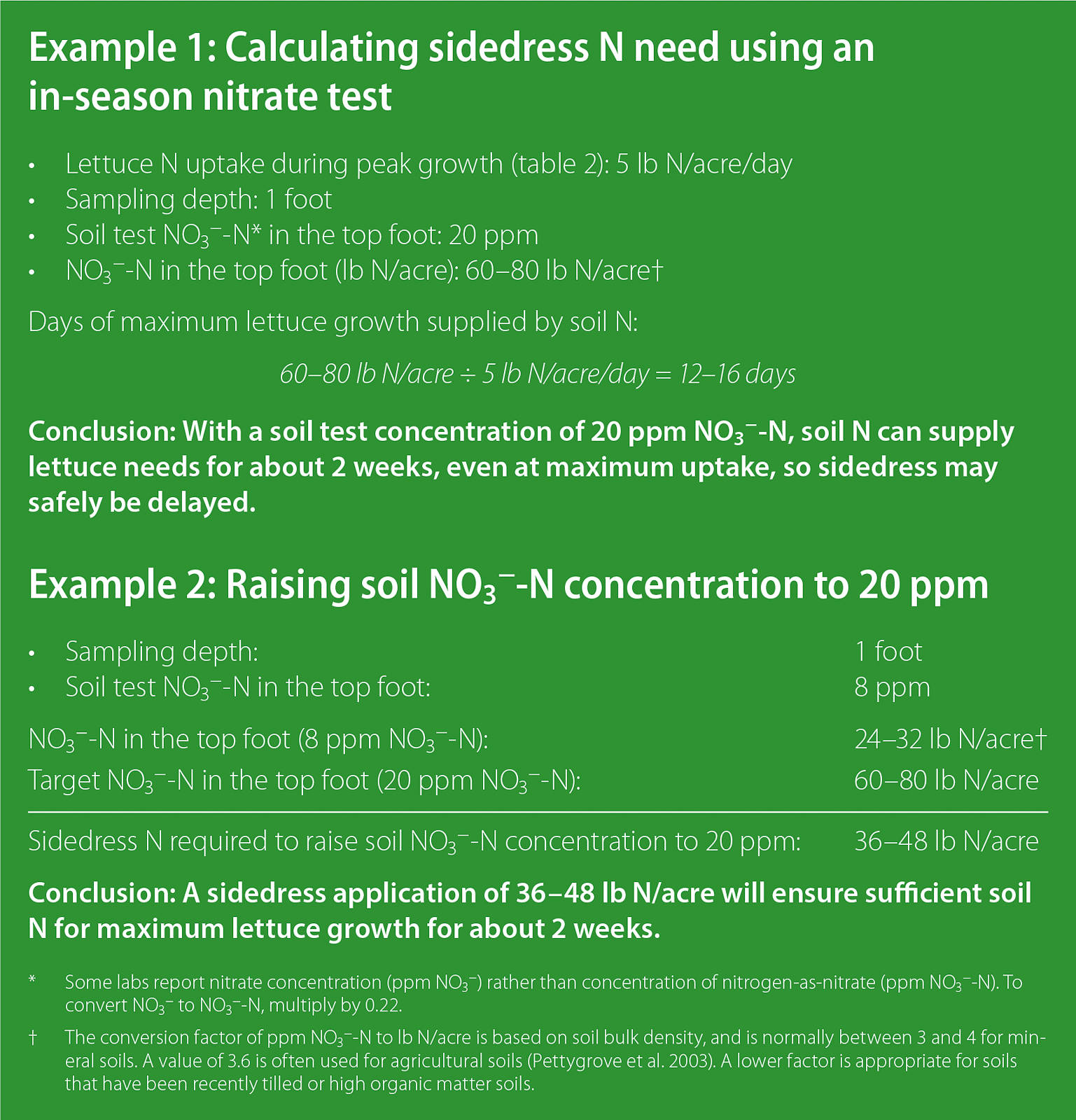

When N is applied several times during the growing season, as in conventionally fertilized vegetable systems, in-season soil NO3− values can be combined with estimates of N uptake during periods of maximum growth (table 2) to determine whether a fertilizer application can be skipped or postponed without affecting yield, and to calculate an application rate based on a target soil NO3−-N concentration. These calculations are demonstrated in figure 2.

TABLE 2. Example daily N uptake rates during periods of maximum uptake for selected California crops

Over the last two decades, much research has gone into developing robust thresholds above which sidedress N is not needed and an application can be delayed for California vegetable crops. Breschini and Hartz (2002) established experimental plots in 15 commercial lettuce fields on the Central Coast, using 20 ppm NO3−-N as a critical threshold. If NO3−-N in the top foot of these plots was greater than 20 ppm, no fertilizer was applied. If it was less than 20 ppm, enough fertilizer was applied to increase it to approximately 20 ppm (fig. 2). This threshold was chosen based on estimated maximum crop uptake rates.

On average, adjusting fertilizer rates based on in-season NO3− tests reduced total N application rates by 43% and reduced postharvest residual N without reducing lettuce yields or quality. Most of the savings came from the first in-season application. Based on this and related trials, the threshold of 20 ppm is commonly used for cool-season vegetables in the Central Coast region (Hartz et al. 2000). Critical thresholds are crop-specific and depend on the maximum N uptake rate and the root system's efficiency. They may not be valid beyond the crop and region for which they were calibrated.

A crop's N uptake rate and the efficiency with which it uses soil and fertilizer N depend heavily on weather, as well as irrigation methods and timing. N demand may be low if crop growth is slowed by factors like cool weather or insufficient irrigation, and even if taken just before the period of maximum uptake, soil NO3− tests may overestimate available N if it is later leached with excess irrigation water. Thus, N application, weather and irrigation cannot be considered independently. UC Cooperative Extension specialists have developed a web-based decision support tool, called CropManage, which allows growers to calculate optimum fertilizer and irrigation rates based on soil NO3− (determined through soil testing) and predicted crop N uptake and water requirements (Cahn et al. 2015). So far, CropManage has been adapted for use in iceberg and romaine lettuce, spinach, celery, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage and strawberry, and it is being expanded to other crops. CropManage is free and accessible online at cropmanage.ucanr.edu.

Pre-sidedress NO3− test (PSNT)

A different threshold approach, the presidedress NO3− test (PSNT), was developed for corn and other rain-fed annual crops in the humid regions of the northeastern and midwestern United States. Samples are taken from the major rooting zone just before the time of accelerated crop uptake. Like the approach described above, the PSNT uses a critical threshold above which a yield response to sidedress N is unlikely. However, the PSNT threshold is based on an empirically derived relationship between spring soil NO3− and the total amount of N supplied by the soil over the course of the growing season (Magdoff et al. 1984). If soil NO3− is predominantly derived from the mineralization of organic N, then the spring NO3− has a consistent relationship to the amount of N mineralized during the season under normal spring and summer weather conditions. In the Northeast and Midwest, threshold values for corn range between 20 and 30 ppm NO3−-N (Blackmer et al. 1989; Heckman et al. 1996; Magdoff et al. 1990). Thresholds have been established for different climatic conditions and a variety of crops, including corn, potatoes, wheat and cabbage (Bélanger et al. 2001; Cui et al. 2008; Heckman et al. 2002; Liu et al. 2003; Magdoff et al. 1990).

However, in areas with low winter precipitation, as in large parts of California, NO3− is often not leached from the root zone with winter rains, and soil NO3− present in spring may therefore either be carryover NO3− from the previous crop or soil N mineralized in early spring (Zebarth et al. 2009). Under these conditions, spring NO3−-N cannot be used to predict N mineralization during the growing season, resulting in a weak relationship between the test results and total N available for crop uptake (Cela et al. 2013; Ferrer et al. 2003; Spellman et al. 1996; Villar et al. 2000).

When winter rainfall is low, PSNT thresholds proposed in the research literature for irrigated corn have been inconsistent, ranging from 13 to 50 ppm in different studies (Cela et al. 2013; Ferrer et al. 2003; Spellman et al. 1996; Villar et al. 2000). These inconsistencies are likely due to high NO3− concentrations in the soil profile below the top foot (Spellman et al. 1996), leaching losses with irrigation water (Magdoff 1991) or low N mineralization potentials of the soils. This variability suggests that in areas with erratic and low winter rainfall, a PSNT threshold value is unlikely to reliably predict whether a sidedress application is needed by irrigated crops that are sidedressed only toward the beginning of a long season. In summary, PSNT thresholds developed for field crops in humid regions, which assume a consistent relationship between NO3−-N present in spring and mineralization over the course of the season, are not likely to be valid for irrigated California crops. In contrast, as discussed above, an NO3− test taken just before rapid crop uptake is a valid tool which allows growers to adjust fertilizer rates for the N that is available at the time of sampling.

Organic systems

Organic systems predominantly rely on N mineralized from organic sources. In traditional organic systems, N fertility comes from soil organic matter and organic amendments incorporated before planting, with no in-season fertilization. In these systems, in-season soil NO3− tests are useful only for monitoring soil N availability. However, some high-N organic fertilizer products are available that release most of their N within a few weeks, and these can be used in organic systems as sidedress materials (Bustamante and Hartz 2015; Hartz and Johnstone 2006). When these materials are used, a soil NO3− test prior to sidedressing may be able to guide application decisions.

A recent study that investigated the use of high-N products on 37 commercial organic processing tomato fields in the Sacramento Valley observed that a soil NO3− test at 3 weeks after transplanting correctly predicted if a field would become N-deficient 60% to 80% of the time (Bustamante and Hartz 2015). In this study, tomatoes on fields with a NO3−-N concentration of greater than 10 to 15 ppm usually did not develop late-season deficiencies. Fields responded to feather meal sidedressed up to 5 weeks after transplanting. Prediction inaccuracy was attributed to differences in irrigation management and reduced efficiency in some fields due to weed competition. These results suggest that a threshold approach similar to that used with conventionally fertilized vegetables may be applicable to organically fertilized crops in California. However, thresholds would not necessarily be similar to those used for conventional crops and would need to be extensively calibrated for each crop and for different soil types.

In-season tissue N testing

Soil NO3− tests can be complemented with in-season plant tissue N analyses or measurements of leaf greenness to assess the N status of crops. However, while a soil test can show whether N is present in excess of crop demand, tissue analyses are usually only reliable for identifying N deficiencies. Tissue N thresholds tend to be better indexes of plant N status in field and permanent crops than in vegetable crops (Hartz et al. 2000; Westerveld et al. 2003).

Postharvest nitrate tests

Postharvest soil NO3− measurements provide a means of assessing whether N was applied in excess of crop need (Tremblay and Bélec 2006). Postharvest samples should be taken in a similar pattern to preplant or in-season samples but more deeply to determine whether NO3− is present below the main root zone. A depth of 3 to 4 feet is often used, in increments of 1 foot.

Postharvest NO3− reflects the balance of N inputs and N uptake during the growing season and also any N losses due to excess irrigation (Schröder 1999). Thus, low NO3− concentrations may be the result of adequate N management, or of excess irrigation that leached NO3− below the sampled layer. For irrigated crops, good management records can help interpret low post-harvest NO3− test results. Relatively high concentrations of NO3−-N below the main rooting zone suggest that adjustments need to be made to irrigation and fertilization practices. In high-yielding lettuce fields in central California, Bottoms et al. (2012) observed that no reductions of yield or quality occurred when postharvest NO3−-N concentrations were as low as 10 ppm in the top foot of soil. Higher concentrations may suggest excess N application.

Nitrate that is present in the soil after the crop is harvested is susceptible to loss if any leaching events occur prior to uptake by a subsequent crop. When post-harvest NO3− concentrations are high in the root zone, growing a nonlegume winter cover crop that takes up the residual NO3− can considerably reduce the risk of NO3− leaching with winter rains.

Scope of use, future research

Soil nitrate tests allow some of the guesswork to be taken out of N fertilization. Samples taken prior to planting and during the season allow growers to safely adjust fertilizer rates for available soil N, while postharvest tests allow them to evaluate whether N rates and irrigation were appropriate. However, nitrate testing has some features users need to be aware of: (1) Samples need to be taken and handled properly for meaningful results, (2) irrigation management needs to be taken into account when interpreting test results and (3) soil NO3− tests do not measure N that will be released from organic sources such as manures, crop residues and soil organic matter over the course of the growing season.

This limitation is important for crops where most of the N needs to be applied early in the season and when a large proportion of the crop's N requirement is mineralized from organic material during the season. Examples are crops grown in high organic matter soils and manured or cover-cropped fields, including organic systems. Since N release depends primarily on the type of amendment, soil properties, moisture and temperature, research that incorporates these factors into a model that can predict N release after soil sampling will make soil NO3− testing a more useful tool in those systems.