Calag Archive

Calag Archive

Trump and U.S. immigration policy

Publication Information

California Agriculture 71(1):15-17. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.2017a0006

Published online January 23, 2017

NALT Keywords

Summary

How a decade of congressional inaction set up today’s debates on an issue crucial to agriculture.

Full text

President Donald Trump campaigned on seven major issues, two of which involved migration: have the United States build — and Mexico pay for — a wall on the 2,000-mile Mexico-U.S. border, and deport the country's 11 million unauthorized foreigners*, over half of whom are Mexican. He has also promised to reverse President Barack Obama's executive orders that provide temporary legal status to some unauthorized foreigners, and to “put American workers first” in migration policymaking.

Since winning the election, Trump has modified some of his positions, notably announcing that deportation efforts would be focused on 2 million unauthorized foreigners convicted of crimes in the United States.

Trump's focus on unauthorized migration during the campaign has had several effects that may prove long-lasting, including polarizing public opinion about what to do about immigration in general and unauthorized foreigners in particular. Migration may join abortion and guns on the list of issues that deeply divide Americans.

Unauthorized migration

Unauthorized foreigners account for a quarter of the 44 million foreign-born U.S. residents. The remainder includes 19 million naturalized U.S. citizens, 12 million lawful immigrants, and almost 2 million lawful temporary visitors such as students and guest workers (Brown and Stepler 2016).

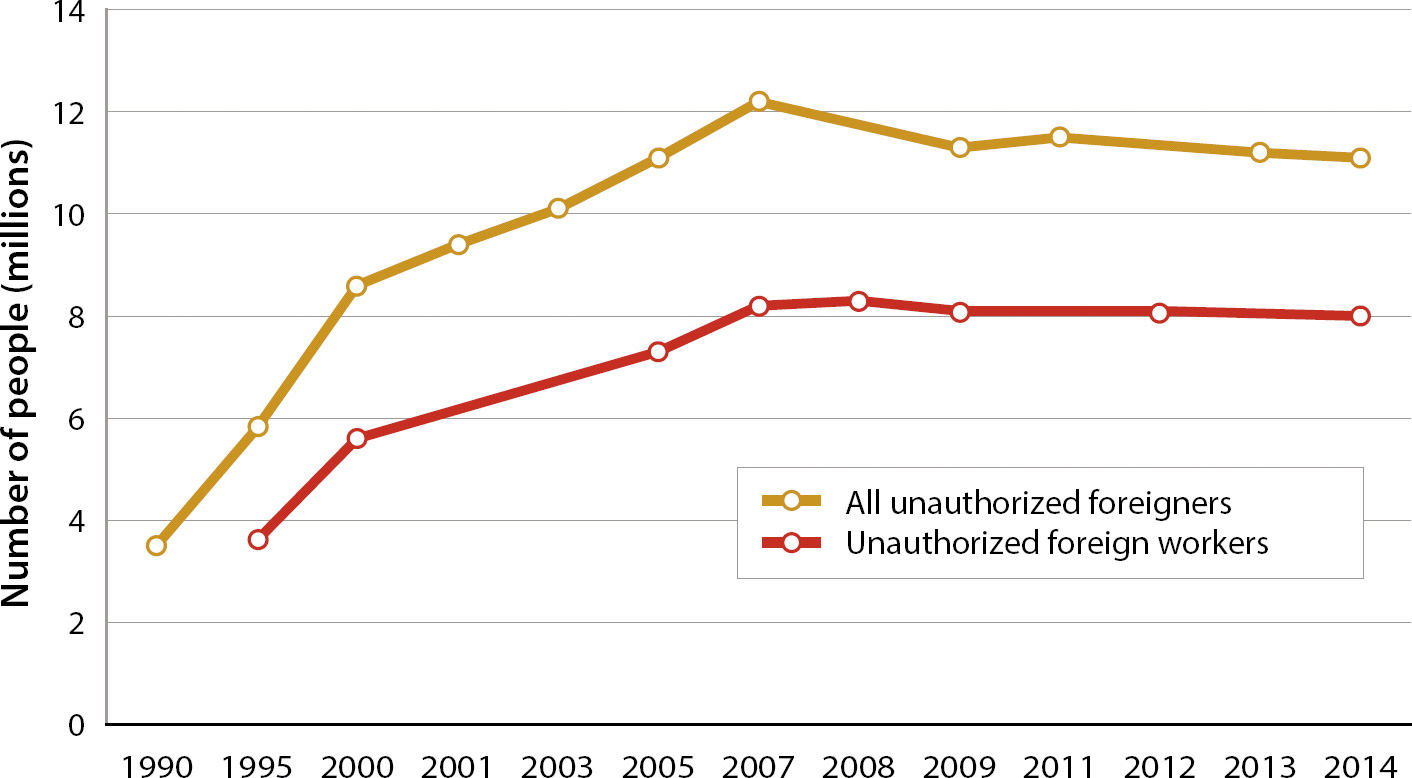

The number of unauthorized foreigners rose rapidly from the 1990s through the mid-2000s, peaking at 12 million in 2007 before declining during and after the 2008–2009 recession (Passel and Cohn 2016a) (fig. 1). Some 8 million unauthorized foreigners are in the U.S. labor force (fig. 1), comprising 5% of a 160-million-strong national workforce that also includes 20 million lawful foreign-born workers (Passel and Cohn 2016b). In 2014, unauthorized workers accounted for 9% of California's workforce.

Fig. 1. Unauthorized foreigners in the United States and in the U.S. labor force, 1990–2014. Source: Passel and Cohn 2016a and 2016b.

Between 2007 and 2014, the number of unauthorized U.S. residents who were born in Mexico fell by a million from 7 million to 6 million, indicating that departures have been exceeding arrivals. That shift is part of a larger trend of fewer new unauthorized foreigners: In 2014, 66% of unauthorized foreigners had been in the country for 10 years or longer, compared with 41% in 2005 (Passel and Cohn 2016a).

Agriculture has the highest share of unauthorized workers of any major industry. Based on data broken out by industry category, about 17% of those employed in agriculture were unauthorized in 2014, followed by 13% in construction and 9% in hospitality. According to data on occupation categories, 26% of those with farming occupations were unauthorized, followed by 15% in construction and 9% each in production and services. Dependence on unauthorized workers is high in certain areas — for instance, unauthorized workers account for over 50% of fruit pickers in California.

Enforcement-only versus comprehensive reform

There are two major policy approaches to deal with unauthorized migrants: enforcement-only, and comprehensive reforms. The latter generally involve three components: enforcement, a path to legalization, and guest worker provisions. Congress has considered multiple proposals of both types in the past decade, but none have become law.

In December 2005, the House of Representatives approved an enforcement-only bill, HR 4437, requiring all employers to verify, using a government database, the legal status of newly hired workers (within a week of hiring) as well as current workers (within 6 years of the bill becoming law). Suspected unauthorized workers would have been required to contact the government to correct their records or be fired. HR 4437 also called for penalties on those who supported or shielded unauthorized foreigners, and ordered the construction of 700 miles of fencing along the Mexico-US border.

Despite pressure from farmers and other employers who hire large numbers of unauthorized workers, HR 4437 did not include new or expanded guest worker programs. It prompted strong reactions from Mexico and outcry in many U.S. cities, including the “A Day Without Immigrants” protests on May 1, 2006. Ultimately, the Senate did not pass the bill.

In May 2006, the Senate introduced a comprehensive immigration reform bill, S 2611. The enforcement provisions in S 2611 were similar to those in HR 4427, with the addition of a system of appeals and reimbursement in cases of government error in the verification process.

S 2611 took a tiered approach to legalization, dividing unauthorized foreigners into three groups based on their length of time in the United States. Under the bill, unauthorized foreigners who had been in the country for at least 5 years (estimated at 7 million people) could become “probationary immigrants” by meeting certain conditions, and would be eligible for regular immigrant visas after 6 more years of U.S. work and tax payments (Migration News 2006). Unauthorized foreigners in the country for between 2 and 5 years (roughly 3 million people) could receive a 3-year temporary lawful work status, but they would be required to return to their countries of origin within 3 years and re-enter the US legally — a so-called touchback requirement. Unauthorized foreigners in the country for fewer than 2 years would be required to leave.

S 2611 also provided for a new large-scale H-2C guest worker program. Employers in any U.S. industry could “attest” that they need to hire migrants, and a foreigner outside the United States with a job offer from such an employer could have paid $500 and obtained a 6-year work permit. Guest workers could change jobs if they received an offer from another employer that had completed the attestation process.

President George W. Bush supported S 2611, but House Republicans did not support the legalization provisions, and the bill died. A similar comprehensive bill, S 1348, was introduced in 2007. Although it included “trigger” provisions, meaning that stepped-up enforcement would have to be deemed effective before new guest worker or legalization programs could begin, it did not pass the Senate.

Obama to Trump

After his 2008 election, Obama said that immigration was not a first-term issue, and instead tackled the economic recession in 2009 and health care in 2010. However, during his first term, Obama met with migrant rights groups frequently and urged them to persuade Congress to act on comprehensive immigration reforms (Migration News 2009). Immigration reform also featured in his 2010 State of the Union speech.

Midterm elections in November 2010 increased the clout of Republicans in Congress, changing the conversation from comprehensive to piecemeal immigration reform. Piecemeal reform meant reviving efforts to pass measures that had bipartisan support, including the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act (introduced several times, first in 2001), which provided a path to citizenship for unauthorized foreigners brought to the United States as children; and the Agricultural Job Opportunity Benefits and Security Act (AgJOBS, originally introduced in 2003) to legalize unauthorized farm workers and make it easier to hire guest workers. Both measures had been blocked in the Democrat-controlled Congress by proponents of comprehensive immigration reform who feared that dealing with the “easy” aspects of immigration reform would become a substitute for comprehensive action.

While campaigning for re-election in June 2012, President Obama created by executive order the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which has so far granted 2-year work and residence permits to 741,000 unauthorized foreigners who arrived in the United States before age 16, are between the ages of 16 and 30, lived illegally in the United States at least 5 years, and have a high school diploma or are honorably discharged veterans.

Many hoped that Obama's re-election in 2012 would encourage Congress to approve comprehensive immigration reform. A bipartisan group of eight senators introduced S 744, an immigration reform bill that increased border and interior enforcement, created a 13-year path to U.S. citizenship for most unauthorized foreigners, and revised and expanded guest worker programs. The Senate approved S 744 by a 68–32 vote in June 2013, but House leaders said they preferred an incremental or piecemeal approach to immigration policymaking, and did not act (Migration News 2013).

With no comprehensive immigration package attracting majority support in Congress, President Obama expanded DACA after the November 2014 elections and proposed the Deferred Action for Parental Accountability (DAPA) program, which would have given temporary legal status to unauthorized foreigners whose children were legal residents. Half of the states sued to block DAPA, and it was not implemented (Rural Migration News 2016).

Unknowns under Trump

During his campaign, President Trump pledged to deport unauthorized foreigners, so it can be expected that he will step up enforcement at the border and move aggressively to remove foreigners convicted of crimes. What is not yet clear is how fast an increase in enforcement could be implemented — for instance, such measures may require congressional funding appropriations.

Much of the debate about enforcement inside U.S. borders is likely to involve relationships between federal, state and local governments to identify unauthorized foreigners.

Under the Secure Communities policy that began in 2008, state and local police shared the fingerprints of all persons arrested with the FBI and Department of Homeland Security (DHS). If suspected unauthorized foreigners were detected, DHS could ask state and local police to hold the person until DHS agents arrived.

Secure Communities was ended in 2014 by the Obama Administration amidst complaints from migrant communities that “innocent activities,” such as being stopped at a DUI checkpoint while driving to go shopping, could result in deportation. Many states and cities went further, declaring themselves to be “sanctuaries” and ordering their law enforcement agencies not to cooperate with DHS.

Trump has promised to withhold federal funds from sanctuary states and cities, but since his election, some cities have approved resolutions pledging not to cooperate with DHS enforcement efforts even if the result is less federal money.

One area where Trump can act quickly is refugee policy. The president, in consultation with Congress, determines the number of refugees to be resettled in the United States each year, and admitted 85,000 in the 2016 fiscal year. Obama proposed to admit 110,000 refugees in fiscal year 2017, but Trump could reduce or stop refugee admissions.

There are many other migration issues that Trump could tackle administratively. For example, Trump could order DHS to resume the workplace raids in meatpacking and other sectors thought to employ large numbers of unauthorized foreigners, or increase the number of audits of the I-9 forms completed by employers and newly hired workers, which could disrupt sectors that hire large numbers of unauthorized workers, such as agriculture. The Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) laid out 79 actions that the president could take administratively, including closer examination of those seeking student, investor and guest worker visas (CIS 2016).

Some administrative actions that President Trump could take are likely to be controversial. He has promised to rescind some of the executive orders issued by Obama, including the one that created DACA. Many have called on Trump to abstain from fulfilling this pledge, emphasizing that the 741,000 DACA youth have been screened and many are now working lawfully. Trump may allow current temporary DACA status to expire rather than to use the information provided by DACA recipients to target them for removal.

Trump's migration agenda is likely to interact with other agendas, including trade. The number-one source of migrants, Mexico, is also the third largest U.S. trade partner, with two-way trade totaling $584 billion in 2015.

One reason for the upsurge in Mexico-U.S. trade is the North American Free Trade Agreement, a trade agreement that Trump has pledged to re-negotiate. Mexico's oil monopoly PEMEX faces declining production and is seeking foreign partners to invest in new oil fields. Since Trump wants to increase fossil fuel production, there could be a complex negotiation with Mexico involving migration, trade and energy. Similarly, with China the number two source of migrants and also a target of Trump's ire for running a trade surplus with the United States, there could be negotiations with China that link migration and economic issues.

Trump's election was a surprise, and there may be similar surprises about his migration policies. His campaign rhetoric changed the vocabulary of politics in many areas, including migration, but it is not yet clear if this changed rhetoric will also change migration policy. The United States is likely to remain the country with the world's largest immigrant population, but the fate of the 11 million unauthorized foreigners is uncertain. The extremes of removing most of them at one end, and putting most on a path to U.S. citizenship at the other, are less likely than an in-between solution that gives most unauthorized foreigners some type of temporary legal status.