Calag Archive

Calag Archive

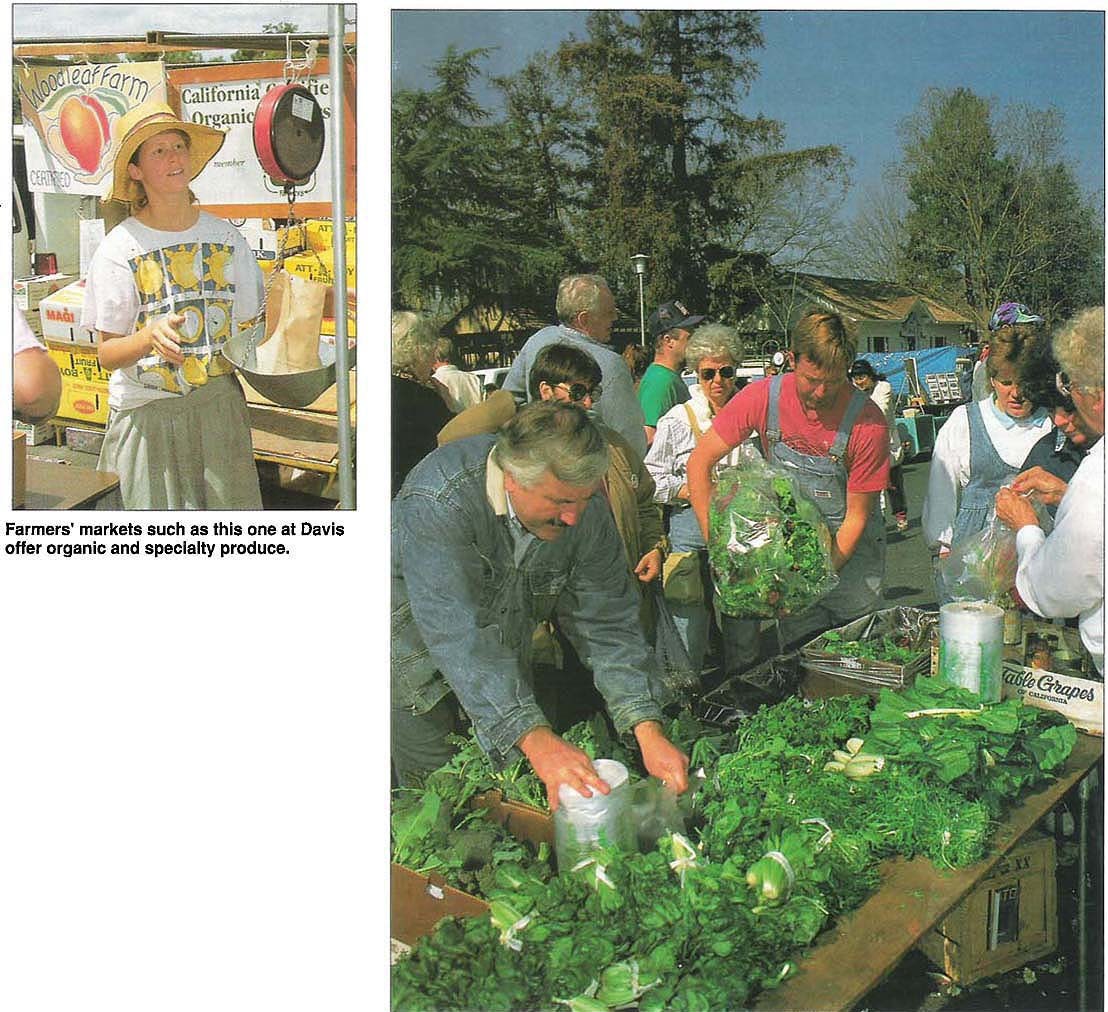

Popularity has spawned diversity - and rules - at certified farmers' markets

Publication Information

California Agriculture 47(2):30-32.

Published March 01, 1993

PDF | Citation | Permissions

Abstract

As a result of the dramatically increasing popularity of farmers' markets, some markets have reached capacity and have been obliged to establish policies about who has priority to sell. Small, part-time, hobby farmers feel particularly vulnerable as rules are established. The best way for them to go: Reserve market space far in advance and offer unique produce.

Full text

Farmers' markets have become so popular in California that they now number 184, compared with 15 in 1978. They range from small markets with five to ten growers to sophisticated operations in large cities with hundreds of growers and total annual market sales in the millions. Their popularity has its down side; as markets become more successful, more growers want to participate, and as more participate, they find themselves forced to compete for sales space, particularly in the larger, busier markets.

The markets' popularity has grown because consumers have become increasingly interested in nutrition, food and environmental safety, and the use of agricultural practices that support these concepts. Farmers' markets have become an established part of many California communities, affording everyone an opportunity to socialize with neighbors and local farmers. They are a very pleasant way to shop.

Farmers' markets usually occupy a finite area within a city or town on a specific day at specific hours. Limited space is available for growers, and at popular markets during summer months, stall space is at a premium. This has resulted in many markets establishing stall space priority rules, reservations, point-and-credit systems for tracking sellers' attendance, and waiting lists for future stall vacancies.

In extreme cases, excluded growers/vendors have filed lawsuits against farmers' market governing boards, arguing that stall space priority rules violate the constitutional rights of participants in public functions and constitute illegal restriction of trade. An undercurrent of dissatisfaction is expressed by some small and/or seasonal growers who feel excluded from farmers' markets due to a combination of factors: fees, rules and regulations, reservations, and competition from larger more diversified growers.

Originally, some farmers' markets in California were started as a way to introduce rare and unusual fruits to consumers. One of the early efforts involved kiwifruit, now a staple of the produce industry. Rare and unusual fruits and vegetables are most often grown by part-time, hobby farms with gross sales of less than $2,500 per year. These are defined as “minifarms.”

With popularity, rules and regulations at farmers' markets have also increased. Do these policies and rules tend to exclude the small, part-time market participant and limit the introduction of new products to consumers? To answer these questions and to learn more about the operation of certified farmers' markets, a survey was conducted in the summer of 1992. One specific purpose was to identify factors restricting and encouraging minifarmer participation in farmers' markets.

Methods

In early summer 1992, California had 184 certified farmers' markets. (“Certified” markets are those inspected and approved by state and local governments.) Markets at a single location, open on different days, were considered separate markets for the purposes of this study. A questionnaire was mailed to a randomly selected sample of market managers of one-half (92) of these markets. Of those mailed, 48 were completed and returned, a 52% response rate. Topics surveyed included (1) general background information about the manager and market, (2) fees paid by growers to participate, (3) policies and rules for reserving space at the market, (4) perceived restrictions to growers' participation in the market, (5) reasons why, if ever, growers were turned away from the market, (6) incentives used by the market to encourage participation, and (7) the managers' opinions as to the three most important factors limiting grower participation in the market and the three most important factors encouraging participation.

Results

This survey revealed the common and diverse characteristics of farmers' markets and, when compared to a 1990 study by the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA), indicated their continued growth and popularity.

One-half of California's markets have been in existence for less than 5 years; 20% are 10 or more years old. From 1979 to 1989 the number of markets grew rapidly, 35 to 40% each year; in the last 3 years (1990–1992), growth has been 10 to 15% each year. The average number of stalls per market has increased from 33 in 1990 to 43 in 1992. The average number of growers participating at each market day during the busy months (April-November) has increased from 24 to 33. Thus, farmers' markets have increased in both number and size. The range in size is equally striking. Nearly one-third of the markets gross less than $30,000 annually, but several gross in excess of $1 million; the average is about $200,000. Many markets did not specify gross sales and many said they did not know. Slightly more than one-half are located in urban areas (50,000 or more people); the rest of the markets are located in rural areas. An average of 10% of the stalls are rented to nonfarming enterprises; more than one-third of the markets rent only to farming enterprises; a small minority (5%) rent more than half their stalls to nonfarmers.

Essentially all markets charge a weekly fee for participation. One-third of the markets charge a flat rate stall fee, ranging from $5 to $35 and averaging $17 per stall per week; the other two-thirds charge a percentage of gross weekly sales ranging from 4 to 10% (average 6%). Markets with flat rate fees have fewer of the smaller, part-time growers participating. In addition, one-half of the markets charge an annual membership fee, averaging $20 per year and ranging from $10 to $40. Two-thirds of the markets are located in counties that also charge a fee, most of which is a certificate transferable to other counties; these fees average $30 annually.

Farmer makeup varies greatly among markets. One-half of the markets, based on this random sample statewide survey, consist of 10% or fewer of small, part-time, hobby growers; another 15% of the markets have 10 to 25% part-time, hobby growers. Only 10% of the markets consist of 90% or more of these growers. Thus, while part-time, hobby farmers are a significant component of many farmers' markets, the majority of participants are small-scale farmers with a greater diversification and volume of produce than the smaller, part-time, hobby farmers.

Market rules regarding participation are continually changing; in the last 2 years, one-fourth of the markets have added market-mix restrictions; other restrictions are related to state direct marketing laws, to fees and/or to grower partnerships.

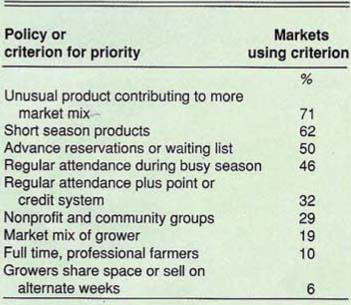

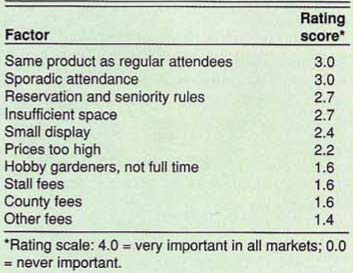

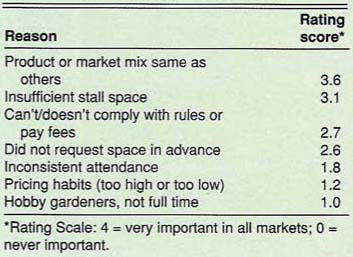

Table 1 lists the percentages of markets using different policies, or criteria, for reserving space at farmers' markets. The most prevalent criteria are unusual products that will provide variety, short-season products, advance reservations and regular attendance. Table 2 lists the relative importance of factors perceived to restrict grower participation at farmers' markets. These are factors from the market manager perspective only, and do not consider grower concerns, such as storage facilities, transportation and distance to market. Three-fourths of the markets indicated that they must turn away growers; the reasons and relative importance are listed in table 3. The data in all three of these tables clearly indicate that market mix is the factor that both limits and encourages grower participation in farmers' markets. Larger markets tend to reserve space for growers with unusual products or with products that enhance market mix. A part-time market participant may experience difficulty reserving stall space unless his or her produce or products differ from that of regular participants.

Space limitations and reservation rules, based on seniority and other point systems, also determine who is permitted to sell at farmers' markets. The 1990 CDFA study indicated a 73% occupancy rate at farmers' markets; this 1992 study indicated a 77% occupancy rate. “Lack of space” was consistently mentioned in a parallel survey of 164 part-time rare fruit growers in California, of whom 44% responded. In response to this high occupancy rate and limited stall space, particularly those in urban areas with more than 20 growers per market, markets have been developing a system of reserving space according to seniority and attendance. Seniority is based on numbers of years of participation in the market, which ensures a grower not only weekly stall space but also increasingly better stall locations within the market. Most markets use a credit or point system to keep track of sellers' attendance. In the desirable, high gross, sales markets, this system favors participation by farmers with larger volume and/or more diversification in produce. Markets with a low percentage of small growers and with larger gross sales are most often urban markets which must restrict participation because of space limitations. Smaller markets have a higher percentage of small, part-time hobby growers, and often have fewer space restrictions than their larger, urban counterparts.

While numerous market restrictions confront smaller growers, many markets also offer incentives for them. More than half of the markets reserve space for unusual or short-season products; one-third of the markets reserve space for backyard growers, and one-fifth of the markets offer reduced fees for these growers. Only 10% of the markets indicated that they do not encourage part-time farmers in some way.

Conclusions

As the popularity of California's certified farmers' markets continues to increase among both growers and consumers, restrictions on grower participation are likely to become more severe. Foremost among restricting factors is the “market mix” or the fact that many growers have too much of the same product, at the same time. Market space and the related factors of reservation and seniority rules are also restrictive. Noncompliance and a general misunderstanding of city, county, state and individual farmers' market rules, regulations and fees are also a problem for part-time hobby growers/marketers.

Growers successful at marketing through farmers' markets either have a diverse mix of produce/products or they produce something that contributes to overall market mix; they have sufficient and continuous supplies throughout the season or year; and they participate in the market regularly. A small, part-time or hobby grower can be successful by offering unusual, quality products that will add to overall market mix and by reserving stall space as far in advance as possible.

CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Animal, Avian, Aquaculture and Veterinary Sciences

Richard H. McCapes (2nd assoc. editor to be announced)

Economics and Public Policy

Harold O. Carter (2nd assoc. editor to be announced)

Food and Nutrition

Eunice Williamson (2nd assoc. editor to be announced)

Human and Community Development

Linda M. Manton

Karen P. Varcoe

Land, Air & Water Sciences

Garrison Sposito

Henry J. Vaux, Jr.

Natural Resources

Daniel W. Anderson

John Helms

Richard B. Standiford

Pest Management

Michael Rust, acting associate editor (2nd assoc. editor to be announced)

Plant Sciences

Calvin O. Qualset

G. Steven Sibbett