Calag Archive

Calag Archive

Farmers increase hiring through labor contractors

Publication Information

California Agriculture 47(4):20-23.

Published July 01, 1993

PDF | Citation | Permissions

Abstract

Farm wages in California, as a percentage of farm sales, fell slightly during the 1980s, partly because many farmers switched to hiring workers through Farm Labor Contractors (FLCs). The abuses frequently attributed to FLCs — including underpayment or nonpayment of wages and (over)charges for housing, transportation and work equipment — have renewed legislative interest in regulating their activities.

Full text

California, the nation's major farm state, accounts for 11% of annual U.S. farm sales and 24% of U.S. farm labor expenditures. California agriculture specializes in producing fruits and nuts, vegetables and melons, and horticultural specialties, such as flowers, nursery products and mushrooms; the state's fruit, vegetable and horticulture (FVH) sales are 36% of the U.S. total, and in the 1987 Census of Agriculture, California FVH farms accounted for 43% of the labor expenditures of such farms.

Reviewed here are trends in California farm employment and wages between 1984 and 1990. These were the years immediately before and after the decade's major change in immigration law: enactment of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 to reduce illegal immigration. Previous studies examined how farmers responded to IRCA on the basis of grower surveys (California Agriculture, January-February 1990); this study is based on the statewide wage and employee data that California farmers report with their Unemployment Insurance (UI) taxes. Because California requires all employers who pay $100 or more in wages to file UI reports listing the names and social security numbers of their employees, these data should be a virtual census of all persons employed on California farms during these years.

IRCA and California agriculture

The legislation that eventually became IRCA began as proposals for (1) sanctions or fines on employers who knowingly hired illegal alien workers and (2) legalization for aliens who had established themselves in the United States. There were initially no special provisions in the proposed legislation for agriculture but, as prospects for immigration reform legislation improved in the early 1980s, California farmers led an ultimately successful fight to add a third pillar to IRCA. California farmers argued that the existing nonimmigrant or H-2 program, through which foreign farmworkers could legally be brought to the U.S., was not workable in California. Instead, they pushed for a “free agent” program that would restrict foreign workers to agricultural employment, but would permit them to migrate from farm to farm.

Congress ultimately rejected this California farmer proposal for free agent foreign workers, but IRCA included a Special Agricultural Worker (SAW) program through which unauthorized workers who had done at least 90 days of qualifying farm work in the 12 months ending May 1, 1986, could become temporary and eventually permanent U.S. residents and workers. More than half of the 1.3 million SAW applications were filed in California, equivalent to three-fourths of the 1 million workers typically reported by the state's farmers to the UI system each year.

IRCA was widely expected to require farmers to adjust to a new era of legal and more settled and stable farmworkers. If the workers were freer to change jobs, one argument ran, farmers would have to offer them higher wages and fringe benefits to keep them in agriculture. Farm labor contractors, who were charged with being union-busting importers of unauthorized workers in the early 1980s, were expected to wither away as farmers began to hire more workers directly.

Given these expectations, IRCA might have led to higher average annual earnings for fewer workers. Wages, however, have fallen since IRCA was enacted. A major reason is that more workers are employed by FLCs than before IRCA, and these FLC employees continue to have lower-than-average earnings. Just as California's Agricultural Labor Relations Act did not lead to a unionized farm work force, so IRCA has not produced a higher-earning farm work force.

The UI data base

UI authorities assign each farm employer a four-digit Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code that reflects the commodity accounting for 50% or more of the employer's sales. This means that a cotton, almond and melon farm is assigned to either the field crops, fruits and nuts, or vegetable and melon SIC, whichever accounts for at least 50% of its sales. If no single commodity accounts for at least 50% of the farm's sales, but more than 50% of the farm's sales are from crops, the farm is considered a general crop farm.

Agriculture is divided into five major (two-digit) SIC codes: crop production (01), livestock production (02), agricultural services (07), forestry (08) and fisheries (09). We obtained all of the worker and wage data reported by California employers with 01, 02 and 07 SIC codes: Within agricultural services (07), we distinguished between farm and nonfarm services: farm agricultural services (FAS) included soil preparation (071), crop harvesting and preparation (072) and farm management services (076); nonfarm agricultural services included veterinary services and lawn and garden services. These nonfarm agricultural services were excluded from our analysis.

UI data are gathered from reporting units and describe average employment and wages paid. Reporting units are farmers employing 50 or more workers. A combination vineyard and winery, each of which employs 50 or more workers, appears in UI data as two employers. Average employment is the number of employees on the payroll (usually weekly in agriculture) for the payroll period which includes the twelfth of the month, summed over 12 months and divided by 12. Wages paid are the total wages paid by farm employers for the entire year.

Farm labor in 1990

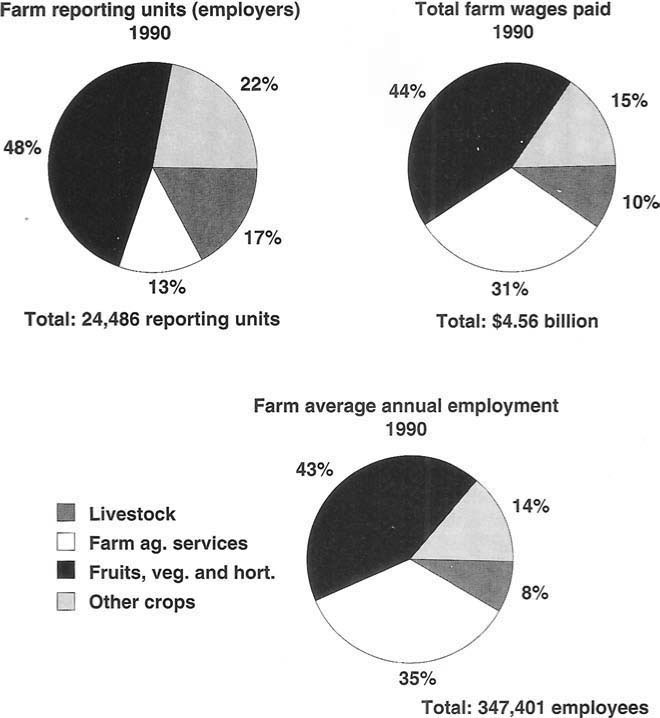

In 1990, more than 34,000 agricultural employers (reporting units) paid almost $6 billion to an average 424,000 employees. Agriculture accounts for about 5% of the state's employers, 1% of the state's wages paid and 3% of the state's average employment. The farming subcomponent of agriculture includes 24,000 employers, $4.5 billion in wages and average employment of 347,000.

Employers producing crops accounted for 70% of the state's farm employers, 59% of the farm wages paid and 57% of average farm employment. These data reflect the importance of FVH employment in the state's agriculture: FVH employers are 68% of all crop employers and 48% of all farm employers. They account for 75% of crop wages paid and 76% of crop employment (fig. 1). California livestock, dairy and poultry farms account for 30% of the state's farm sales, but only 17% of the state's farm employers, 10% of farm wages and 8% of farm employment. The agricultural service firms employing workers for farm tasks include 13% of the state's farm employers, 31% of the wages paid and 35% of farm employment.

Trends between 1984 and 1990

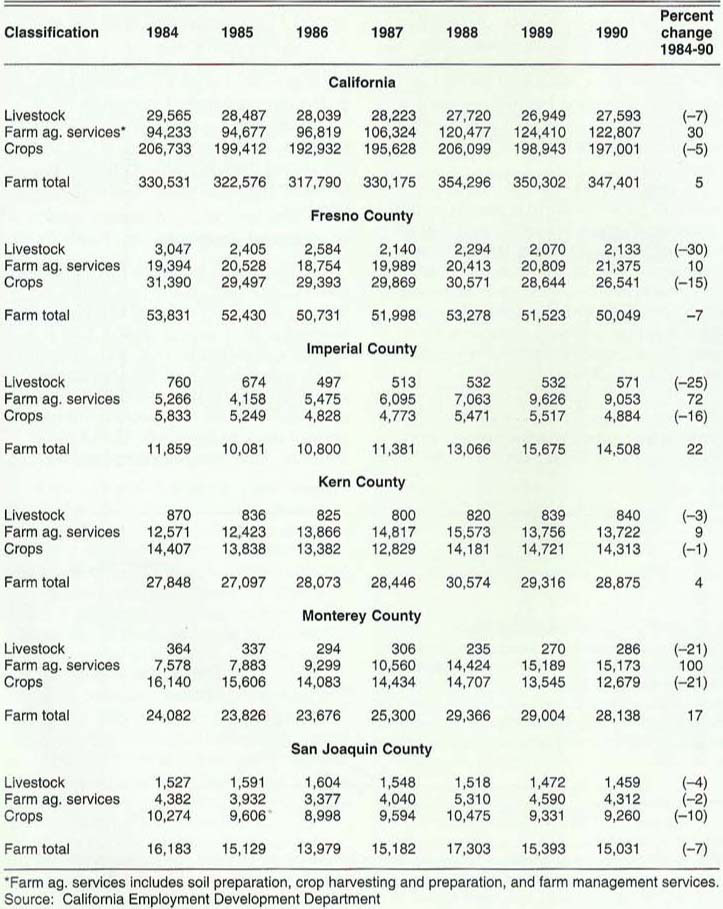

The number of farm employers or reporting units fell 12% between 1984 and 1990, with the decline accelerating in the late 1980s. Farm wages rose 31%, but agricultural services wages rose more than twice as fast as the wages paid directly to workers by crop and livestock producers. Average farm employment rose 5%; this overall rise masks a decrease in employment by farmers who hire workers directly and a 30% jump in the average employment of farm agricultural services firms.

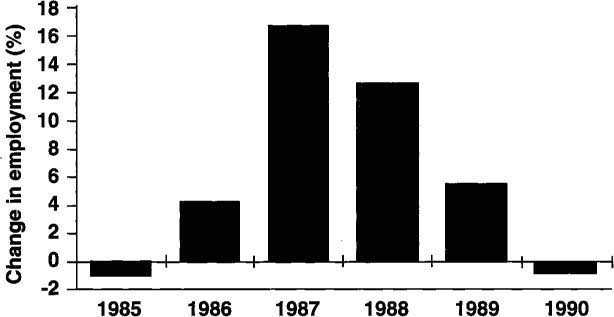

The single most important employment trend is the rising importance of FLCs. In 1990, 935 FLCs accounted for 21% of average employment on California farms, up sharply from 15% in 1984. The sharpest increases in average FLC employment occurred in 1987 and 1988 (fig. 2). However, workers employed by FLCs tend to have lower average annual earnings than workers hired directly by growers. The average year-round equivalent job in California agriculture would have paid $13,000 in 1990. FLCs paid only 60% as much ($7,700). Increasing FLC employment tends to lower average wages for farmworkers.

Fig. 2. Percentage change in average Farm Labor Contractor (FLC) employment: 1985–1990. For example, average FLC employment rose from 52,745 in 1986 to 61,547 in 1987, or 17%. Source: California Employment Development Department.

County patterns

The shift to hiring farmworkers through FLCs and other agricultural service firms is noticeable at the county level. The five counties selected for analysis — Fresno, Imperial, Kern, Monterey and San Joaquin — accounted for 31% of California farm employers, 38% of wages paid and 39% of average employment.

The number of farm employers fell in each of these counties between 1984 and 1990 and in every subcategory except FAS in Monterey. Wages paid generally rose fastest for FAS firms. Especially striking are Imperial and Monterey counties, where crop wages fell or rose only a little while FAS wages more than doubled. The 44% increase in total value of agricultural production in these five counties during these years clearly illustrates a shift from hiring workers directly to hiring them through agricultural service firms such as FLCs.

The trend toward having agricultural service firms such as FLCs bring workers to farms is most noticeable in the employment data. In 1984, the average employment of workers hired directly by crop producers was larger than FAS employment in each of the counties (table 1). By 1990, FAS employment was larger than directly-hired employment in two of the five counties (Imperial and Monterey), almost as large in Kern County and catching up in Fresno County. There were especially sharp jumps in FAS employment between 1987 and 1988; that is, a 36% 1-year jump in Monterey County and a 32% 1-year jump in San Joaquin County.

Impact of IRCA

There is evidence that IRCA played a significant role in this shift toward getting farmworkers through FAS firms. Testimony to the IRCA-created Commission on Agricultural Workers in 1990 and 1991 suggests that some farmers, seeking to avoid IRCA-related paperwork burdens and potential sanctions for hiring illegal alien workers, began hiring workers through FLCs. In many cases, competitior between FLCs to bring workers to farms prevented them from receiving higher commissions for the additional responsibilities imposed on them by IRCA.

The shift toward FLCs and other agricultural services helped to hold down wages as a percentage of value of agricultural production. In 1984, farm wages were 22% of the $15.8 billion value of the state's agricultural production; in 1990, they were 21% of $21.6 billion. However, holding down farm wages by turning to FAS firms has a price. FAS firms, especially FLCs, are linked in the public's mind and in enforcement data to low wages and poor conditions for farmworkers. For example, the National Agricultural Worker Survey (NAWS), conducted between 1989 and 1991 by the U.S. Department of Labor, found that 44% of the workers employed by FLCs paid for their own work equipment, as opposed to 17% of direct-hire workers. The NAWS also found that 28% of FLC employees were charged by their employer for transportation to the work site, compared with just 7% among direct-hire workers.

Newspaper series, such as the Sacramento Bee's December 1991 “Fields of Pain,” have bolstered support in the California Legislature for making farmers jointly or strictly liable for any labor law violations committed by FLCs who bring workers to their farms. Reporters described vulnerable farmworkers who were not paid promised wages, or were paid minimum wages but were then charged so much for housing, rides to work and work equipment that their effective earnings were far less than $4.25 hourly. Many workers were reluctant to complain. In many cases, the FLC had disappeared. Even if the FLC was available, agreements were usually oral, so that resolving disputes is a time-consuming process of determining who is the most credible witness.

Farmworker advocates argue that farmers who benefit from farmworker labor should be liable for any law violations committed by the FLCs who provide the workers. In this way, they argue, farmers will police the activities of FLCs far more effectively than government agencies can. One such law, in effect since January 1992, requires FLCs to register with County Agricultural Commissioners. It states that growers are responsible for any labor law violations committed by an FLC on their farm if they have not checked to be sure that the FLC is registered to operate in the county.

Legislative proposals in Sacramento and Washington D.C. would make farm employers solely or jointly liable with FLCs for any violations of wage, housing, pesticide and transportation laws. Farm employers are now liable for such violations if they are committed by an unregistered FLC, but the proposals in the California Assembly (AB90) and the U.S. House of Representatives (HR 1173) would make them liable even if the FLC is registered, in effect following the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act and eliminating FLCs as sole employers.

Conclusions

IRCA did not prevent California agriculture from expanding in the 1980s. The total value of agricultural production in California rose 37% between 1984 and 1990; average employment on California farms rose 5%. Farm wages, as a share of value of production, fell from 22% in 1984 to 21% in 1990.

California farmers were able to expand farm sales without raising wages by hiring more workers through farm-oriented agricultural service firms, including FLCs. These employers usually bring workers to farms, and their average employment rose 30% between 1984 and 1990. In counties such as Monterey, FAS employment doubled, while employment of workers hired directly by farmers fell more than 20%.

Hiring more workers through FAS firms appears to have helped to hold down labor costs, but it has also led in some instances to poor wages and working conditions. As a result, there is more legislative interest in making farm operators jointly or strictly liable, along with FLCs, for the payment of farm wages and the observance of farm labor laws.