Calag Archive

Calag Archive

Radio is effective in teaching nutrition to Latino families

Publication Information

California Agriculture 50(6):14-17. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v050n06p14

Published November 01, 1996

Abstract

A series of five nutrition education lessons was broadcast over Spanish-language radio in a major metropolitan and a semirural area of southern California. Pre- and postbroadcast interviews with a random sample of enrollees were used to examine differences in nutrition-related knowledge, practices, and frequency of eating selected foods. In both broadcast locations, knowledge and practice gains were significant, but reported food-frequency patterns did not reflect change. Listeners liked the lessons and home-study guides, and identified specific ways they had applied the information. Spanish-language radio appears to be an effective medium to deliver nutrition education to Latinos.

Full text

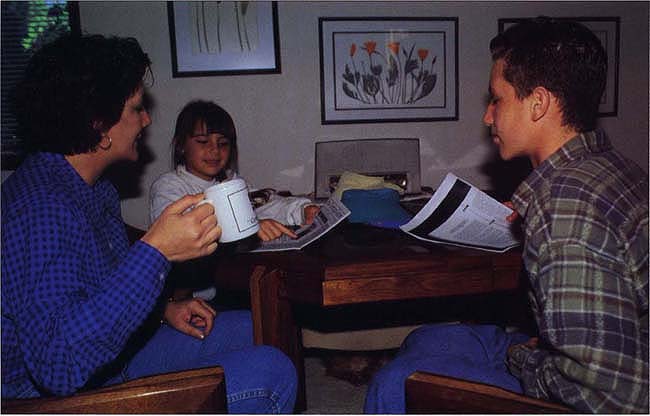

A series of five nutrition education lessons was broadcast over Spanish-language radio in a major metropolitan and a semirural area of southern California. Participants also used a home-study guide, which reinforced the nutrition messages.

The need for providing nutrition education to a diverse population has dramatically increased in the United States at the same time that diminishing resources challenge nutrition educators to provide services. Mass media, including radio, is one way that a relatively small number of nutrition educators can communicate with large audiences. In developing countries, radio programming has been used to reach rural populations with varying degrees of success. In the United States, using radio to teach nutrition and advocate specific behavioral changes in food practices appears to be underutilized or is rarely documented. However, surveys indicate that Latinos listen to radio to a greater extent than Anglos do. This study investigated whether nutrition education via radio could increase knowledge and stimulate positive behavioral change in food-choice habits among Latino radio listeners.

It is important that nutrition educators, while attempting to reach large and diverse audiences, make an effort to deliver culturally appropriate programs addressing specific needs of identified ethnic groups. Latinos — which are the fastest-growing demographic group, representing 26% of California's population — have unique nutrition education needs. Nutrition studies among this population have identified traditional dietary practices that should be supported and newly adopted ones that could be improved (Romero-Gwynn). For example, eating beans, corn tortillas and rice are healthy practices, but increased use of mayonnaise and high-fat salad dressings are not.

Building on a pilot program in San Bernardino County (Romero-Gwynn and Marshall) and other counties, five 20-minute nutrition education scripts were refined and a companion study guide was developed. An informal conversation, plática, format was used to teach specific dietary modifications to Lations while supporting traditional, healthy practices.

Two non-overlapping, full-time, Spanish-language radio stations offering popular music to adult listeners in southern California — one serving a major metropolitan area and the other a semirural area — cooperated, providing an opportunity to see whether radio had different impacts in the two settings. Radio listeners could enroll by dialing a toll-free phone number to avoid long-distance charges. Home-study guides to accompany the radio lessons were mailed to enrollees.

Spanish radio nutrition course

“Nuestra Comida Es Buena Pero Se Puede Mejorar” (“Our Diet Is Good But It Can Be Improved”), is a nutrition education program designed for Spanish-speaking people of Mexican descent. Its five nutrition lessons address dietary practices specific to Mexican-Americans, with attention to supporting preexisting, positive food patterns and to improving practices, identified through prior research, among the intended audience. Programs were written and recorded in an interview format and included food terms commonly used by the target audience. Radio topics were: Let's Eat More Foods Rich in Calcium; Eat More Fruits and Vegetables; Meat, Eggs, Beans and Nuts in Our Diets; Tortillas, Bread and Cereal in Our Diets; and Let's Use Less Fat and Sugar in Our Diets.

The lessons followed the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans by discussing the food groups included in the Food Guide Pyramid. Each lesson was accompanied by a mailed home-study guide written at a fifth-to-sixth-grade literacy level. The guide, written in a question-and-answer format, reinforced the nutrition messages in each radio program. In both the radio lessons and the home-study guides, adaptation of the Dietary Guidelines to the dietary practices of the Mexican-American food culture was stressed.

Lessons were broadcast weekly over a 5-week period through a metropolitan Spanish radio station in Los Angeles and a semirural station in Santa Maria (Santa Barbara County). Publicity during the month before the broadcasts included public service announcements broadcast by the two Spanish radio stations; brochures placed in community centers, WIC centers, Head Start, Departments of Social Services, and other public places frequented by Latios; and articles in local Spanish-language newspapers.

Interested persons could register for the free course by completing the mail-in enrollment form attached to the brochures, or by calling a toll-free number. Study guides and a broadcast schedule were mailed to each person who registered. Per announcements during the series of broadcasts, five prizes solicited from local businesses were awarded on the last day of each series to randomly selected participants. Certificates of participation were mailed to all registered participants with additional nutrition information and a collection of recipes that applied recommendations included in the radio lessons.

Evaluation description

An experienced, bilingual, nutrition education assistant was trained to enroll persons calling the toll-free number, to select samples of enrollees, and to conduct interviews with persons in the samples. A sample of 35 persons was randomly selected from the first 100 persons to enroll from each broadcast area. Participants were to be interviewed before and after the lesson series. Most interviews were conducted in the evening hours; some participants could be reached only on weekends. Only 27 of the 35 could be contacted for interviews before the broadcasts began in the semirural area. Three urban and two semirural enrollees were not available for the postbroadcast interviews. (There were no apparent differences between persons who were and were not available for interview.) The final number of urban interviews conducted was 67 (35 pre- and 32 postbroadcast); 52 interviews were conducted with listeners in the semirural area (27 pre- and 25 postbroadcast).

The average age of enrollees in the urban sample was 37; the rural enrollees were younger, with an average age of 29 years. For both groups, the average number of school years completed was 8.1.

The questionnaire used in the interviews was adapted from one used in the earlier Romero-Gwynn study. Items in a variety of formats — true-false, multiple choice and open-ended — were used to measure respondents' knowledge about nutrition, food buying and preparation practices, and the frequency of eating selected foods. Examples of true-false items included: Fruits and vegetables contain a lot of calcium; Eating fewer flour tortillas will reduce fat intake; Adults need less milk than a 4-year-old child. Open-ended questions included: What do you look for on the label when buying breakfast cereal? milk? fruit juice? How can one save money when buying milk? meat? beans or rice?

After the radio lessons, respondents were more familiar with what to look for on food labels when buying cereals, milk, fruit juice and margarine.

The instrument was tested for language clarity with 10 Spanish-speaking individuals not included in the study samples, but otherwise believed to be comparable to the radio class enrollees.

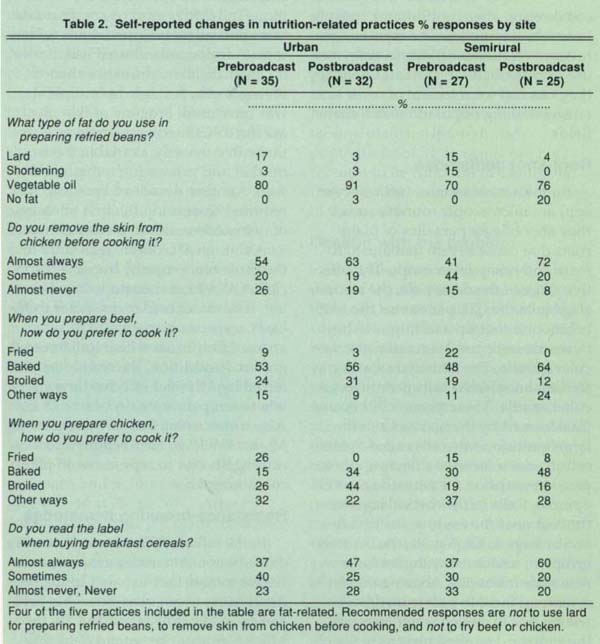

An index of nutrition-related knowledge was created by summing all correct answers to knowledge items. Participants were asked how often (daily, weekly, etc.) they ate 13 selected foods (familiar items in the Mexican-American diet selected to represent the major food groups and foods with high fat content); responses were converted to daily frequency. Size of portions was not assessed. A nutrition-practices score was constructed by totaling correct responses (those recommended in the radio lessons) to five items, four of which were related to fat in the diet — of major concern in Latino nutrition. The fifth item was label-reading in the grocery store.

Impact of the radio lessons

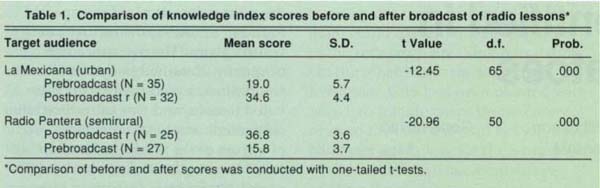

The effect of the radio lessons on enrollees' nutrition-related knowledge was significant and substantial. The mean score on the knowledge index (table 1) almost doubled in the urban sample and more than doubled in the rural sample. The probability that the difference between before and after scores could have happened by chance alone was less than one in a thousand. After the radio lessons, respondents were more familiar with what to look for on food labels when buying cereals, milk, fruit juice and margarine. Evidence of knowledge gain was implicit in responses to open-ended questions; for instance, food-buying practices recommended in the radio lessons were frequently mentioned in response to open-ended questions about how to save money when buying food; and respondents mentioned several ideas from the lessons on how to get calcium when a person does not use milk. Overall, the percentage of “Don't know/Not sure” responses dropped from the pre- to the post-broadcast interviews, particularly for the open-ended questions.

With regard to consumption of selected foods, the radio lessons did not seem to have an impact on the reported frequency of eating fruits and vegetables, which was low both before and after the lessons. This did not take into account the size of portions. More than one brief radio broadcast and associated study guide are probably necessary to make a difference.

The radio lessons appeared to have a beneficial effect on practices that could reduce fat consumption, one aspect of Latinos' diet that needs improvement. Four items in the nutrition-related practice index were related to fat consumption (table 2). The average score of the urban sample on the 5-point practice index changed from 3.3 recommended practices prebroadcast to 4.0 after the lessons (P = .01). For the rural group, the average practice index score was 3.2 before and significantly higher at 4.2 after the lessons (P = .01).

Open-ended questions regarding application of information learned in the radio lessons and home-study guides were included in the postbroadcast interviews. Only one listener reported not using information from a lesson. Typical comments referred to buying and using low-fat milk; buying more fruit and vegetables for the family; using less sugar; eating more legumes; switching to bread; and eating fewer flour tortillas.

Listeners' reactions to the home-study guides were positive across all topics. More than half of the persons interviewed had read all of the home-study guides, and about two-thirds of the listeners had read the materials with their spouse, children and/or friends. Only one person found the guides difficult to read.

Overall, comments on the use of Spanish-language radio for nutrition education were very supportive. Listeners said they had learned a lot about food, but wanted more classes on nutrition and also needed to review what they had already heard. Several suggested other radio lessons on various aspects of parenting and on money management.

Study limitations

Participants in this study were a random sample of persons within the broadcast areas of two Spanish-language radio stations in southern California who had taken the initiative to sign up for the nutrition education course advertised on those stations. Presumably there were other listeners; no information exists on who or how many those might be. The sample size was limited to fit the resources available.

Persons in the sample were restricted to those who could be reached by phone for an enrollment interview, and who said when contacted after the radio lessons that they had actually listened to the broadcasts. About 16% of the original sample was lost in these ways.

Conclusions

Participation in the Spanish-radio, nutrition education course was effective in improving nutrition-related knowledge and selected practices in both the urban area and semirural area. Of special importance is the impact on knowledge and practices directed toward reduction of fat intake.

Not only was the radio course successful in improving listeners' nutrition-related knowledge and selected practices, but it captured the interest of the intended Latino audience in both a metropolitan and semirural area. The audience in this study — mostly foreign-born with limited schooling — was motivated to register by telephone or by completing a mail-in enrollment card, and did listen to the broadcasts. This contrasts with participants in another study (unpublished) who were personally recruited and signed up at child-care and WIC centers, but who did not listen. This suggests that self-initiated action (proactivity rather than compliance) is a potent influence on listening participation. It may be that listenership can be expanded by continuing educational broadcasting on Spanish radio.

For further reading

Romero-Gwynn, E., et al. 1993. Dietary adaptations among Latinos of Mexican descent. Nutrition Today 23(4):6–12.

Romero-Gwynn, E. & Marshall, M. 1990. Radio: untapped teaching tool, Effective nutrition education for Hispanics. Journal of Extension 28:9–11.