Calag Archive

Calag Archive

Income value of private amenities assessed in California oak woodlands

Publication Information

California Agriculture 66(3):91-96. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v066n03p91

Published online July 01, 2012

Abstract

Landowners in California were surveyed using a contingent valuation technique to assess its usefulness in estimating the monetary income value of private amenities from their oak woodland properties. Private amenities — such as recreation, scenic beauty and a rural lifestyle — are considered an important influence on rangeland owners, but few studies have attempted to place a monetary income value on them. Landowners were asked to estimate the maximum amount of earnings that they were willing to forgo before selling their property to invest in more commercially profitable, nonagrarian assets, and the proportion of the land price that they thought was explained by private amenities from their land. On average, landowners were willing to pay $54 per acre annually for private amenities, and they attributed 57% of the land price to them. Regression analysis revealed that the landowners’ willingness to pay per acre decreased as property size increased. This approach sheds light on how landowners value the benefits of land owner-ship and offers insights for outreach and policy development for privately owned oak woodlands.

Full text

Private amenities from California oak woodlands — including benefits such as recreational opportunities, scenic beauty, living in the country, and protecting wildlife and water quality — are important influences on landowner decisions and income (Huntsinger et al. 2010). Efforts to value these amenities in California and other Western states have included analyses of the relationship between land prices and property size (Pope 1985), tree density (Diamond et al. 1987), distance to open space (Standiford and Scott 2002) and production value (Torell et al. 2005). The most common commercial land use in oak woodlands is livestock grazing (Huntsinger et al. 2010), but throughout the West, private amenities are believed to be an important factor in explaining why land prices for ranches exceed their commercial production value (Torell et al. 2005). With land-use change and fragmentation threatening the extensive habitat and watershed benefits provided by private oak woodlands, understanding landowners’ decisions and values is a conservation priority.

More than 80% of California's oak woodlands are privately owned. The monetary value of such land's private amenities — noncommercial benefits to landowners such as beauty and open space — was assessed using a contingent valuation technique, which asks people what they would be willing to pay to maintain the asset or be compensated for its loss.

Advocates of conserving areas that produce crops, livestock, hunting or timber, as well as other ecosystem services, call them “working landscapes,” a term that fits oak woodlands well. The concept of ecosystem services is commonly defined as the benefits people obtain from ecosystems. Continued ecosystem services from oak woodlands depend largely on the commercial profitability of ranches, their amenity value to their owners and the opportunity costs of competing land uses — in other words, on the cost of maintaining oak woodland ownership measured as the foregone benefits from using the land for something else or selling it. Estimating values for private amenities can contribute to our understanding of landowners’ decisions and their responsiveness to outreach and policies for oak woodlands. This is also important for assessing the economic value of the natural resource component of land.

Valuing private amenities

The Commodity Cost and Returns Estimation Handbook for measuring income in rangelands and other agricultural lands (AAEA 2000) does not consider private amenities as part of landowner income, despite the longstanding characterization of ranchers as lifestyle consumers. As Pope (1985) states, many land buyers are seeking an investment they can “touch, feel, experience and enjoy” and a place where they can be associated with farming or ranching. The System of National Accounts, the internationally agreed-upon standard set of recommendations for how to compile measures of economic activity, also fails to include the flow of private amenities as part of landowner income (United Nations 2009). In this paper, we attempt to fill this gap by applying a contingent valuation technique designed to estimate the monetary income value of such amenities to private owners of oak woodlands.

Previous studies have quantified the amenity component of rangeland market prices in the western United States using the hedonic pricing technique, in which the price paid for a good is used to estimate the component values of that good's characteristics (Pope 1985; Torell et al. 2005). This approach is useful for understanding the contribution of private amenities to land prices but does not offer a direct estimation of monetary income values. Others have also studied the role of private amenities in U.S. rangelands using alternative approaches (Huntsinger et al. 2010; Smith and Martin 1972).

Contingent valuation is a method used to estimate values for environmental resources such as reducing the impacts of contamination, preserving the beautiful view of a mountain, or conserving wildlife. These resources do not have a market price as they are not directly sold, but they do give people utility and have economic value. Values are derived by asking people what they would be willing to pay (or willing to accept) to obtain or maintain (or to be compensated for the loss of) a good or service.

We drew on a sample of oak woodland owners in California to assess the usefulness of contingent valuation in estimating the monetary income value of private amenities from oak woodland properties. For the sake of brevity, the term “amenities” is used here to include all the economic, nonmarket ecosystem goods and services that a landowner obtains from the land, including heritage and succession rights. The contingent valuation technique that we use is not designed to separate different components of the estimated amenity values.

Landowner sample

California oak woodlands extend over 5 million acres, and more than 80% are in private ownership (CDF-FRAP 2003). Landowners from two studies were used to develop a diverse sample for testing the contingent valuation approach. In the primary study in 2004, landowners were identified based on Forest Inventory Assessment plots previously used to assess hardwood volume in California (Bolsinger 1988); the methods are described by Huntsinger et al. (2010).

Response rate.

The Dillman four-wave method was used (Dillman 1978), resulting in a 64% survey response rate with 98 completed questionnaires, encompassing more than 10% of California oak woodlands on an acreage basis. The response rate attained overall is considered more than adequate (Connelly et al. 2003; Huntsinger et al. 2010; Needham and Vaske 2008), but the response rate for the main contingent valuation question was lower. To augment valid responses to the contingent valuation question for modeling purposes, 17 additional oak woodland owners were interviewed as part of a study of foothill landowners (Sulak and Huntsinger 2007), making the final number of respondents 115.

Respondent demographics.

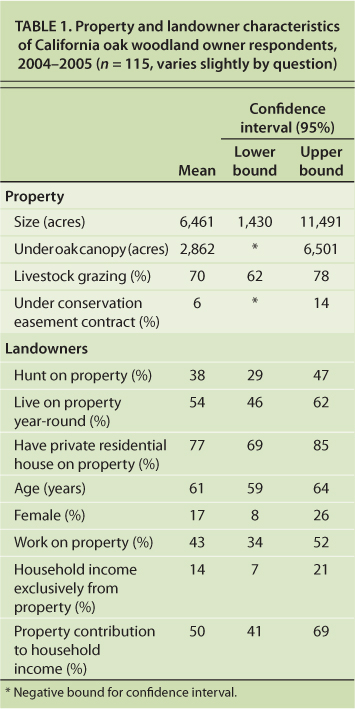

The demographics of the combined sample were similar to those of the primary study. The average property size in our sample was large, with almost half of the property under the oak canopy (table 1). Livestock grazing was the most common land use, while hunting was practiced by 38%. Conservation easements were present on 6% of the sampled land. More than half the landowners lived on the property year-round, and 77% had a house on the ranch. The average landowner was middle-aged and male, 43% worked directly on the property and 14% obtained household income exclusively from the oak woodland. Half of landowner household income came from the ranch.

TABLE 1. Property and landowner characteristics of California oak woodland owner respondents, 2004–2005 (n = 115, varies slightly by question)

Responses to contingent valuation

Many respondents found it difficult to answer the main contingent valuation question (described below), resulting in a 26% valid response rate (30 answers). This is at the low end of response rates now argued to be typical (Connelly et al. 2003) but is comparable to those in other contingent valuation studies of private landowners (Banerjee et al. 2007; Shaik et al. 2007). Responses were from a spectrum of property sizes and land uses appropriate for illustrating the use of the contingent valuation approach to estimate amenity income values on a case study basis (Needham and Vaske 2008). This number of responses is also comparable with other studies whose objective was closely related to ours; Diamond et al. (1987) used 30 responses in their study of oak woodland property values and oak tree density.

In their comments, landowners indicated that they found the amenity-benefits valuation question challenging, and some were simply unable to provide a monetary income value. This is common in contingent valuation studies because many people are not able or do not want to state their willingness to pay. This type of response (commonly known as a protest response) is not a zero value but rather a nonresponse.

In our sample, it was significantly more likely that owners of larger properties with residences on them, and those earning a greater proportion of household income from ranching, would not answer the contingent valuation question (Welch's t-test, P value < 0.10). Similarly, Kim et al. (2008) found that cattle producers were reluctant to answer contingent valuation questions.

Contingent valuation questions

Private amenity consumption implies that the land is bought or held not only as a capital investment but also for its consumptive value (Pope 1985) — a behavior termed an “investor-consumer” rationality. The contingent valuation design tested for this rationality and the values of private amenities were estimated through competitive market simulation, allowing landowners to choose among options for investment and income. Landowners stated their maximum willingness to pay for the annual enjoyment of their oak woodland amenities.

Deer graze in oak woodlands in Mendocino County. Nearly 40% of the private landowners surveyed hunted on their land. Hunting is believed to be an important component of private amenity income, although this study was not designed to subdivide such income into components.

In theory, to obtain an amenity income value, the costs of land operations associated with the landowner's amenity enjoyment should be subtracted from the estimated amenity value; for example, the cost of thinning trees that obstruct a view or the cost of residential housing should be deducted. This was not possible with the survey data gathered, however, and as a result we assumed that the costs of land operations were all attributable to commercial activities. The joint production of amenities and commodities makes it reasonable to assume that most land operations would not occur without a commercial purpose, such as the sale of stumpage for trees that need thinning.

We developed the contingent valuation question based on the assumption that oak woodland owners give up, or are willing to give up, potentially higher earnings from alternative investments in order to enjoy amenities from their land. The difference in commercial earnings from the landowners’ investments in their land and the best potential alternative investments they could hypothetically make — and would be willing to give up to keep their land — is the maximum price that they were willing to pay for amenities from their land. We posit that this willingness to pay represents the income value of the landowner amenities. In the questionnaire, respondents were asked:

Imagine that you could earn more money by investing in other assets (for example, stocks or bonds) of comparable risk and time frame. How much is the maximum amount of earnings you are willing to give up, per year, before selling your property in order to invest in an alternative that brings a higher return? (Keep in mind that by selling your estate your family and friends give up the exclusive right to enjoy the natural surroundings of your land, and you can no longer pass down this property to future beneficiaries): ______.

Although the question asked landowners about their total willingness to pay, we interpreted the results using per acre values: we divided the amount stated for the whole property by the property's total number of acres. The questionnaire also asked landowners to state what they thought the market price of their property was and to allocate this price, as a percentage of the total, among different benefits they obtained from their property; in other words, to say how much they thought each benefit contributed to the woodland's market price. The values estimated with these two questions were not market values derived from real transactions but rather values stated by the landowners based on their perceptions about the land market.

The questions were worded as follows: “How much do you estimate the current market value of your land to be without buildings or other infrastructure?” and “How important are each of the following to your personal value for your property? Express each as a percentage of the total value, so that the percentages total 100% at the bottom.”

The benefits offered were timber and firewood, livestock and pasture (irrigated and nonirrigated), crops, hunting, enjoyment of the landscape, having friends and relatives visit, and “others.” Although livestock management activities do not affect land price the same way as having pasture does, it was difficult for landowners to separate livestock from pasture benefits, and both were presented together.

The stated land price might include the value of other assets intertwined with the land (e.g., leases), but these assets would also be linked to private amenity consumption. Thus, the estimated amenity benefits would likewise derive from these assets. For example, Torell et al. (2001) discussed how private amenity consumption was incorporated into the grazing fee paid by ranchers. Our contingent valuation questions yielded the information necessary to obtain an estimate of the amenity benefits through the stated willingness to pay (WTP) and the market value (LV) of the property through the stated land market price. This allowed us to calculate the stated amenity profitability rate (rA) as the ratio of the amenity benefits divided by the total land value (rA = WTP/LV) — the percentage of nonmarket, monetary amenity return obtained by the landowner relative to their land investment (capital value).

Valuing oak woodland amenities

Investment value.

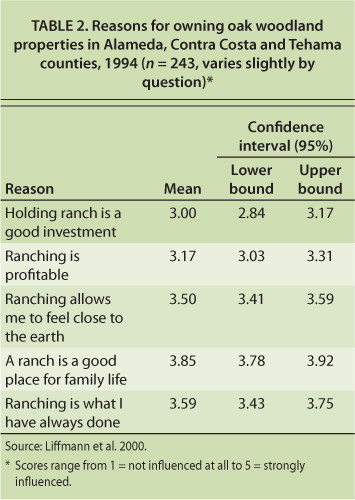

Fewer than 9% of respondents believed that their annual earnings were enough to make the oak woodland a better investment than other options. About half thought that adding land appreciation to earnings was enough to make the woodland a better investment, while 44% thought that they would earn more with other investments, even considering land appreciation. Yet they had persisted in land ownership to the date of the survey, despite what was, at the time, a highly competitive real estate market. Results from a 1994 survey of oak woodland ranchers in California, in which respondents scored the factors influencing the retention of their oak woodlands, showed that the most highly ranked values were lifestyle and tradition (Liffmann et al. 2000) (table 2).

TABLE 2. Reasons for owning oak woodland properties in Alameda, Contra Costa and Tehama counties, 1994 (n = 243, varies slightly by question)∗

Willingness to pay.

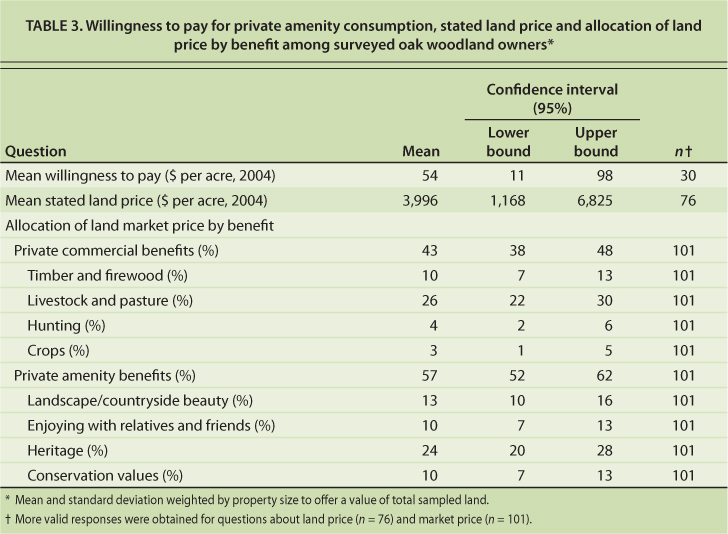

The mean willingness to pay for private amenity consumption obtained from valid responses (n = 30) was $54 per acre (table 3). The mean stated land price was almost $4,000 per acre, and the amenity component represented 57% of the land price. Of the amenity or noncommercial components, heritage was most important; among the commercial benefits, livestock and pasture made the main contribution (table 3).

TABLE 3. Willingness to pay for private amenity consumption, stated land price and allocation of land price by benefit among surveyed oak woodland owners∗

Knowing how private amenity values vary depending on landowner and property characteristics is relevant to understanding how they relate to land uses and socioeconomic patterns. We used regression analysis to look at the influence of the variables (table 1) and the stated land price on willingness to pay per acre.

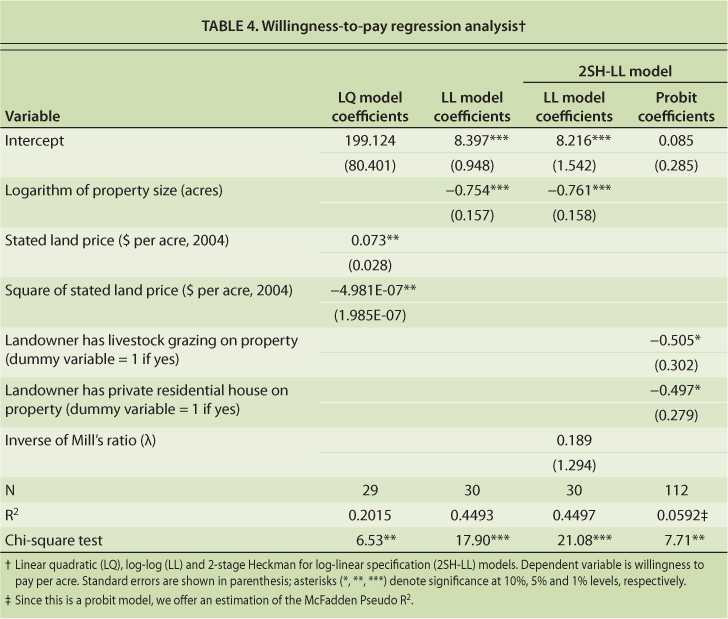

To select the regression models, the significance of explanatory variables was first tested individually, revealing three significant variables: acres of property size, acres of property under canopy cover and stated land price. Since the first two variables are correlated (they incorporate similar information), we kept acres of property size because it refers to the whole property. We chose a linear-quadratic (LQ) specification for a model with stated land price and a log-log (LL) specification for a model with acres of property size as explanatory variables, because they offer the highest fit (R2) (table 4). The LQ model incorporates a quadratic term to test for nonlinear effects on the dependent variable. In the LL model, both the dependent and the explanatory variable take their natural logarithms. This model is appropriate when the variables present a wide range of values, as in this case.

The LQ model showed a positive association between willingness to pay per acre and the land price stated by the landowners, with a negative sign for the square of this term. This implies that amenity values increased as stated land price increased, but that the contribution of amenity values to land price was relatively lower for oak woodlands with higher stated land prices (table 4). The LL model showed a saturation effect in amenity values, since willingness to pay per acre decreased with property size.

In an economic context, saturation means that above a certain level of consumption, additional units of the good do not add more value to the good. Our analysis showed that landowners with large properties did not obtain more amenity benefits with additional units of land because their amenity consumption was saturated. An LQ model type with property size as explanatory variable (data not shown) also showed this saturation effect, but the LL model was a better fit (table 4).

Property size.

Graphing the willingness to pay per acre from the LL model showed that it decreased nonlinearly with property size (fig. 1A), with marginal decreases of less than $1 per acre for property sizes larger than 1,000 acres. This implies that the total willingness-to-pay function became gradually flatter as property size increased (fig. 1B). However, there was significant variability in the LL function, and the 95% confidence interval of the property size at which the marginal decrease of willingness to pay became less than $1 per acre was 200 acres for the lower bound and 10,000 acres for the upper bound. (These are estimated using the lower and upper bounds of the 95% conficence interval of the regression coefficients of the LL function.)

Fig. 1. Saturation effect of property size on landowners’ willingness to pay (WTP). (A) A log-log (LL) function of WTP per acre shows a nonlinear decline with property size; WTP/acre = exp [8.397∗∗∗ (0.948) − 0.754∗∗∗ (0.157) Ln (acres)]; Ln = natural logarithm; standard errors are shown in parentheses; and asterisks (∗∗∗) denote significance at the 1% level. (B) Corresponding total WTP function obtained by multiplying WTP per acre predictions from LL function (A) by acres of property size of corresponding observation (WTP = [WTP/acres] × acres); total landowner amenity value becomes gradually more constant (the function becomes flatter) as property size increases.

Given that landowners with larger properties had a lower willingness to pay per acre and were more likely not to answer the contingent valuation question, our willingness-to-pay estimations may be overvalued. However, Spash and Hanley (1995) suggest that nonrespondents in contingent valuation studies may find it difficult to answer these questions because of the high value they attach to these goods, and the potential net effect in our estimations of incorporating responses from these nonrespondents was hard to discern.

We also present a two-stage Heckman sample selection bias model for the log-log specification (2SH-LL), the one with the highest fit (table 4). This model implies first a probit regression that estimates the probability of giving a valid answer to the willingness-to-pay question from all available observations. We found that landowners with livestock and a residential house on the property were more likely to not answer the willingness-to-pay question. Property size had the same effect, but it was correlated with the other variables; we decided to leave it out of the final model. The estimated parameters from the probit regression were then used to calculate the inverse Mills ratio (a measure of the sample selection bias from valid willingness-to-pay answers), which was then included as an additional explanatory variable in the LL specification model. However, the inverse Mills ratio coefficient was not significant, and the model fit was not improved compared with the LL model (table 4).

Landowner benefits from woodlands

The results showed that the amenity profitability rate (rA) was 1.35% ($54 per acre divided by $3,996 per acre, times 100) for the average landowner in the sample. This is a nominal rate, since landowners were not asked to consider inflation when answering the question. This value was low compared with other estimations of amenity profitability rates in oak woodlands in other Mediterranean climates (Campos et al. 2009), probably because properties in California are larger and likely closer to the saturation point for amenity values.

This saturation effect finding is important for woodland conservation policy. If landowners can obtain nearly the same amenity value from small properties as from large properties, they do not need large acreages if amenities are the only motive for owning the land. In contrast, income from grazing increases steadily with area of woodland range. This finding supports the concept of working landscapes, where private land conservation is achieved by combining multiple ecosystem services, including landowner amenities or other personal benefits (Huntsinger et al. 2010).

Owners appreciated amenities such as their land's beauty and rural location, but a significant number were unable to place a monetary value on them. Above, a ranch house in the Gold Rush country of Calaveras County.

When developing outreach or policy, it is important to consider landowner goals, motives and needs. The amenity values California ranchers have reported as important include having the freedom to make land management decisions and relative autonomy on their lands, as well as enjoying natural beauty, feeling close to the earth and passing property on to heirs (Huntsinger et al. 2010; Liffmann et al. 2000). At the same time, having adequate forage to maintain a commercial herd and the availability of infrastructure for marketing livestock products were also crucial to those owning most of the larger properties (Sulak and Huntsinger 2007).

Since most oak woodland owners are motivated by environmental as well as lifestyle amenities, many want to maintain and steward the land, and they have responded to incentives that help them improve wildlife habitat and environmental quality while bolstering production conditions (Symonds 2008). Fortunately, oak woodland owners enjoy and value amenities that benefit society: the public enjoys natural beauty, wildlife and many other ecosystem services from well-stewarded lands. Too often, it is assumed that production and conservation are inversely related, but as we illustrate here, there are also synergies that can be built upon to create effective conservation strategies for private lands.

In future studieincome should be identified and assessed separately. Further testing of ways to ask contingent valuation questions might result in a higher res, the costs associated with amenity sponse rate; however, when respondents were asked why they had not answered, a typical comment was that the value of the land to them was beyond measure in dollars. Ironically, those missing values are an important part of what we seek to understand.

![Saturation effect of property size on landowners’ willingness to pay (WTP). (A) A log-log (LL) function of WTP per acre shows a nonlinear decline with property size; WTP/acre = exp [8.397∗∗∗ (0.948) − 0.754∗∗∗ (0.157) Ln (acres)]; Ln = natural logarithm; standard errors are shown in parentheses; and asterisks (∗∗∗) denote significance at the 1% level. (B) Corresponding total WTP function obtained by multiplying WTP per acre predictions from LL function (A) by acres of property size of corresponding observation (WTP = [WTP/acres] × acres); total landowner amenity value becomes gradually more constant (the function becomes flatter) as property size increases.](http://calag.ucanr.edu/archive/?file=fig6603p95.jpg)