Calag Archive

Calag Archive

WIC fruit and vegetable vouchers: Small farms face barriers in supplying produce

Publication Information

California Agriculture 69(2):98-104. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v069n02p98

Published online April 01, 2015

NALT Keywords

Abstract

By October 2009, all 50 states had implemented a revised WIC program with produce vouchers for millions of eligible families. USDA economists had projected the vouchers would raise net farm revenues by $76 million. In response to such a significant policy change and market opportunity, a UC Agriculture and Natural Resources Cooperative Extension team of researchers conducted a pilot project to test the ability of small farms to market produce locally to WIC-authorized stores known as A-50 vendors. They also interviewed store owners and produce distributors to determine how produce was entering the supply chain to the A-50 vendors. The pilot project was not successful in helping small growers enter the supply chain. The analysis indicates that it is improbable that small farms will be selling much produce to A-50 vendors; growers’ price expectations are unlikely to be met since these vendors are competing with large retailers. And although the vouchers can be redeemed at farmers markets, very few are because the process is cumbersome for growers and shoppers.

Full text

As of October 2009, all 50 states had introduced produce vouchers as part of a federal food assistance program that was projected to generate significant increases in fruit and vegetable sales and new opportunities for growers. The federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) began distributing monthly fruit and vegetable vouchers (F&V vouchers) to program clients. The cash-value vouchers were originally $6 per child between 1 and 4 years old and $10 per woman; in June 2014, the voucher for children increased to $8 (USDA FNS 2007). The cost of adding F&V vouchers to the specific foods and amounts that may be purchased with vouchers each month was offset by reducing monthly allowances for infant foods, milk, cheese, infant formula and other dairy products, as well as for juice and eggs.

The F&V vouchers had been long awaited by the produce industry (Karst 2009). WIC serves about 9 million low-income women, infants and children each month, including about half of the infants in the United States (USDA ERS 2012). In their analysis of the potential impact of the policy changes on WIC expenditures, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) economists projected a net increase of $76 million in farm revenues from the F&V vouchers (Hanson and Oliveira 2009).

A-50 vendors play a significant role in the distribution of fresh produce to WIC clientele in California, handling 28% of the redeemed fruit and vegetable vouchers.

Early findings

In a pilot study conducted in California in 2001 using cash-value vouchers for fruits and vegetables, 90.7% of the farmers market vouchers and 87.5% of the supermarket vouchers were redeemed by WIC participants (Herman et al. 2006). A California study that involved cross-sectional telephone surveys in September 2009 and March 2010 reported small but significant increases in fruit and vegetable intakes by WIC clients and their families (Whaley et al. 2012). Similar findings were obtained in a Connecticut study by Andreyeva et al. (2012); they determined that the availability of fresh fruits and vegetables increased significantly at A-50 stores, but there was no increase at other stores that accepted the vouchers, such as supermarket chain stores. (An A-50 vendor is a WIC-authorized store with more than 50% of its food revenues generated from sales of WIC foods.)

In a 2010 telephone survey of 52 managers of small WIC-authorized stores in eight major cities, most perceived their increased sales of fresh fruits (75%) and vegetables (69%) as due to the F&V vouchers; no changes in sales were reported for processed (canned and frozen) fruits and vegetables (Ayala et al. 2012). Managers who reported a daily delivery of fruit to their stores were more likely to perceive a greater increase in sales, implying that the freshness and higher quality led WIC clientele to purchase more fruit. This is consistent with earlier findings from our project — interviews in 2010 of ethnically diverse WIC participants in Tulare, Alameda and Riverside counties indicated that the key factors determining their produce purchase decisions were produce quality and freshness (Kaiser et al. 2012).

The F&V voucher program

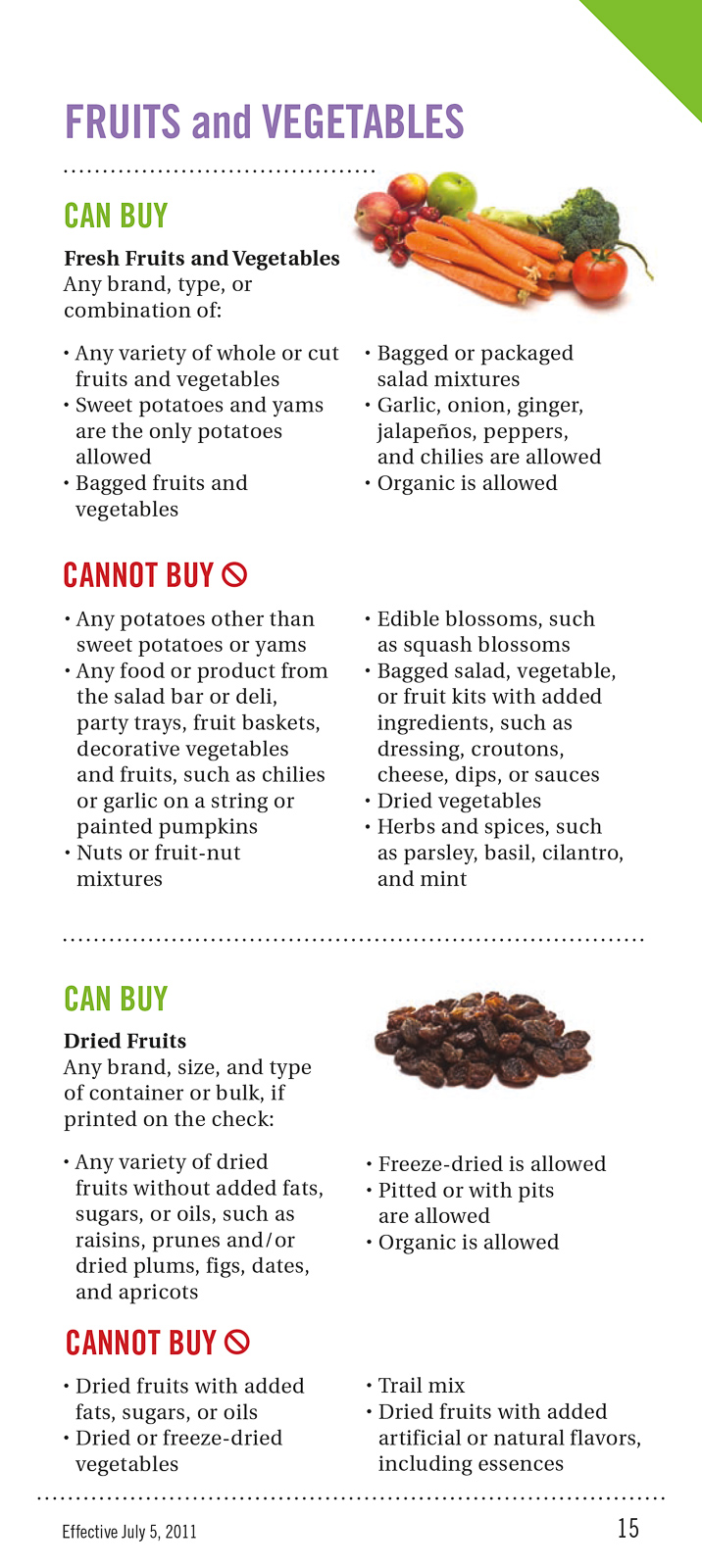

California's Department of Public Health administers the state's WIC program. Federal regulations set the parameters for the amounts and types of foods allowed to be distributed to different categories of WIC participants: pregnant, nursing or postpartum women; infants (0 to 11 months); and children (12 to 60 months) (USDA FNS 2007). States are required to offer at least two fruits and two vegetables — fresh, canned, frozen and dried fruits and vegetables are all allowed — but states may impose more stringent requirements. WIC-approved vendors in California must offer at least five varieties each of fresh fruits and vegetables, in addition to fresh bananas. Twelve states allow only fresh fruits and vegetables; California is one of 24 states that also allows canned and frozen fruits and vegetables. The produce items not allowed are listed by Kaiser et al. (2012).

WIC clientele can redeem food vouchers at various types of retail outlets (states have the option of allowing participants to redeem vouchers at farmers markets also; California does allow redemptions at farmers markets). Only F&V vouchers have a stated cash value. The other WIC food vouchers are redeemable for allowable products in the food product category; for example, the cereal voucher is redeemable for a package of cereal that is on the list of approved brands, is at least 51% whole grain and weighs between 12 to 36 ounces. The entire F&V voucher must be redeemed in a single transaction. If the purchase value is less than the voucher amount, no change is given. If the purchase value is more than the voucher amount, the WIC client must pay the difference or charge it against her food stamp benefits.

In California, WIC produce vouchers may be used to purchase fresh, frozen or canned fruits and vegetables.

Giving a cash value to the F&V vouchers introduced an element of price sensitivity to WIC clients’ shopping practices that had not existed before, and created competition among vendors for WIC shoppers. Each retail chain or store owner determines the quantity and quality of produce that can be purchased with the F&V vouchers. Until F&V vouchers were added, A-50 vendors competed only on nonprice factors, such as brand selection and location (McLaughlin et al. 2013).

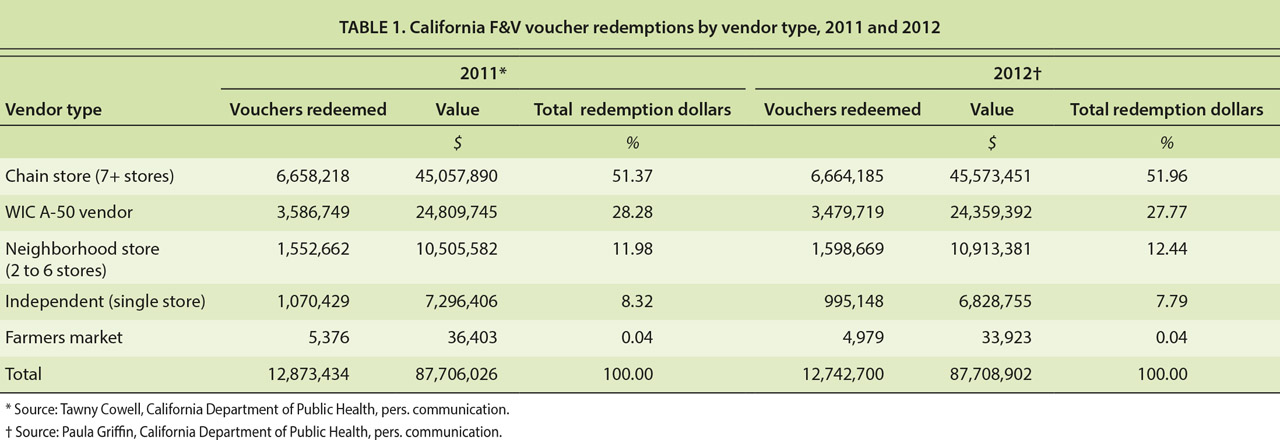

There were 42,651 WIC vendors nationwide in 2010, with WIC redemptions totaling $4.1 billion (Mantovani 2012). In California, there were 5,426 WIC-authorized vendors as of June 19, 2012. The overall redemption rate for F&V vouchers during 2011 was 90.7% in California. Redemptions totaled $87.7 million in both 2011 and 2012 (amounting to roughly 1.7% of total retail produce sales in the state); they are displayed by vendor type in table 1.

A-50 vendors play a significant role in the distribution of fresh produce to WIC clientele in California, handling 28% of the redeemed F&V vouchers. In 2004, 15 states had A-50 vendors, and of those 1,180 vendors, 715 were in California (US General Accounting Office 2006). A-50 vendors include small food markets that serve primarily WIC participants and WIC-only stores, which carry only WIC products. California now has approximately 900 A-50 vendors; they constitute 15% of the state's authorized WIC vendors and account for more than one-third of the state's total WIC redemptions (McLaughlin et al. 2013).

UCCE farm-to-WIC project

In 2010, our team of UC Agriculture and Natural Resources Cooperative Extension (UCCE) academics initiated a pilot project to test the ability of small farms to market produce to WIC clients. The project tried to connect small-scale growers with local A-50 vendors in three counties: Alameda (highly urbanized), Tulare (largely rural) and Riverside (mixed) (Kaiser et al. 2012). It had two objectives: (1) to enhance small growers’ financial viability and access to new markets and (2) to provide WIC clients with better access to more nutritious, high-quality, culturally preferred produce and expanded nutritional knowledge. As noted by Campbell et al. (2013), this is a challenging undertaking; their literature review describes the tension between the prices needed to support small-scale growers and the affordable healthy food sought by low-income consumers. Our interviews in 2010 revealed the same tension: “small stores in low-income urban and rural neighborhoods find it challenging to supply a variety of high-quality produce at affordable prices” (Kaiser et al. 2012).

This guide from the California WIC Program shows authorized fresh and dried produce options. In addition to fresh bananas, WIC-approved vendors in California must offer at least five varieties each of fresh fruits and vegetables.

The UCCE team first conducted market research with WIC clients in the three counties to identify preferred vendor partners and produce items to target in the project (Kaiser et al. 2012). The farm advisors narrowed the proposed produce list to those crops that could be produced locally (in the same county) by small-scale growers. The UCCE project team prepared a pamphlet for store owners in each county, highlighting the results from the WIC client interviews. We contacted the preferred vendors, provided each manager with a county-specific pamphlet and requested a meeting with the manager to discuss logistics for purchasing WIC-popular crops from small local growers.

In July and August 2010, the UCCE team initiated contact with buyers from the stores (including regional grocery chains) preferred by the WIC clients. Only the produce buyers from A-50 vendors were interested in the project. It would have been cumbersome for regional grocery chains to develop separate produce procurement programs for their WIC clients. In each of the three counties, we met with the owners of at least three A-50 stores that had been identified by some WIC clients as preferred vendors.

Our meetings in Alameda and Tulare counties included one small grower identified by the UCCE farm advisor as being interested in supplying produce directly to the A-50 vendors. In Alameda County, the farm advisor worked with a small grower to prepare a list of crops and facilitated a meeting at the grower's farm with the buyer from an A-50 store chain, Prime Time Nutrition. The grower had investigated packaging options and was ready to package the produce as requested by the buyer. The buyer was impressed with the small farm; there were rows of sweet corn and various other vegetables, staked heirloom tomatoes, patches of watermelons and ripe strawberries. At the end of the farm tour, the conversation turned to quality, quantity, price and delivery logistics. The grower and buyer planned to continue price negotiations, with the prospect of a delivery within 2 weeks. There were a few brief follow-up phone calls to clarify certain points, but then the communication stalled. Unanswered phone messages from the grower and the buyer piled up, and finally contact between the two parties ceased.

In Tulare County, the farm advisor introduced a small grower to the owner of three A-50 stores. The grower agreed to sell watermelons from his 4-acre farm to the store owner. When the store owner asked for just two bins of melons to supply his three stores, the grower decided that it was not cost effective for him to load and deliver them to the stores; instead, he sold the entire harvest at one time to a wholesale buyer.

The farm advisor in Riverside County offered to take the purchasing manager of Fiesta Nutrition, a small A-50 chain, and the buyer for Fiesta Nutrition's distributor on a tour to meet local growers who could supply produce to the 15-store chain. Despite repeated attempts, the store purchasing manager never responded to the invitation. No individual growers in Riverside County communicated with WIC store buyers.

Based on these experiences, we realized that connecting individual small growers with A-50 vendors directly would be very difficult due to problems of pricing, communication and the economics of delivering small quantities of individual crops to individual vendors. We then decided to evaluate the feasibility of linking small growers and A-50 vendors through distributors, and identified several regional produce aggregators and distributors that purchased from local small growers.

To supply the Prime Time Nutrition stores in Alameda County, we contacted ALBA Organics, a regional produce distributor based in Monterey County that distributes for organic farms in the region, including four new small-acreage growers who had transitioned from being farmworkers through ALBA's farmer training program. In March 2011, Prime Time Nutrition's buyer purchased 160 cases of lemons from ALBA Organics, which had been bought from a small organic citrus grower in the San Joaquin Valley. In May 2011, during the peak of strawberry harvest, ALBA Organics sold 500 boxes of strawberries from small growers to Prime Time Nutrition for their Northern California stores. For both transactions, the buyer's truck picked up the boxes at ALBA Organics’ cooler facility in Salinas. These two purchases totaled just over $10,000, of which slightly less than $5,000 went to the growers. ALBA Organics’ manager was satisfied with these sales and was willing to negotiate on price to secure future business from Prime Time; however, Prime Time's buyer did not return his calls.

In Tulare County, the farm advisor attempted to contact the head buyer for a regional produce distributor that made direct deliveries twice each week to the three targeted Tulare County A-50 vendors. He did not get any response from the buyer.

In Riverside County, the owner of the three targeted A-50 vendors in the Coachella Valley contacted a project team member in 2011, seeking assistance in locating a full-line produce distributor that would deliver to his desert stores. The UCCE team located a nonprofit food security organization, which had plans for a campaign to encourage local farmworkers to eat local produce. The organization's director said she was willing to purchase produce from local growers and deliver to the A-50 vendors, but she was unable to package the produce as needed and deliver it for a price that the store owner was willing to pay. The store owner was left delivering produce from San Diego to his stores in the Coachella Valley.

Thus, in this distributor-focused phase of the project, we were generally unable to facilitate sales between small farms and stores serving WIC clients because the parties could not agree on prices. To better understand why it was so difficult to connect small growers andA-50 vendors, we examined supply chains that were successfully providing produce to WIC clients. Table 1 shows that large store chains are the dominant suppliers of produce to WIC clients in California. These stores include large grocery chains, such as Safeway and Savemart; box stores such as Food4Less and FoodMax; and general merchandise stores, such as Walmart and Target. These chains have a diverse client base and had significant sales of produce before the introduction of WIC F&V vouchers in 2009, so the impact of the vouchers on their produce sales and supply chain is likely to have been minimal. Therefore, we focused our examination on new produce supply chains that were developed at A-50 stores when F&V vouchers were introduced. To this end, we interviewed owners and managers of A-50 stores as well as produce distributors that serve such stores.

Survey of A-50 store owners

In 2012, we interviewed five owners or managers of A-50 stores in the three counties in our pilot project regarding their experience in transitioning to F&V vouchers, including how they sourced the new produce they had to carry, the financial investments needed and the price competition they faced. The five stores were part of retail chains that ranged from four stores to 100 stores. (More than 230 A-50 vendors in California are chain stores.)

The store owners reported that the introduction of F&V vouchers had led to either an increase in or had no impact on the number of WIC shoppers in their stores. However, even those whose sales volume increased did not report increased profits. Milk, egg, cheese and juice vouchers were reduced when the F&V vouchers were added, and those products tend to have higher margins than produce.

Additionally, major changes had to be made in the stores to prepare for fruit and vegetable sales, including installing coolers and reconfiguring counter space and shelving to display produce. Product mix, pricing and packaging had to be determined to allow customers to maximize variety with their vouchers, staff had to be trained and produce suppliers located. The owners faced challenges related to these changes, such as obtaining financing to purchase the refrigeration and display equipment, and obtaining information regarding proper produce handling. A companion article in this issue (Kaiser et al. 2015, page 105 ) describes our project's educational activities with staff at A-50 stores.

Four of the store owners rely on produce distributors. The fifth owner, who operates four stores, decided that it was more cost effective to buy directly from farms and packinghouses around Fresno and Bakersfield, as well as from produce terminals, and to have a staff member pick up and deliver the produce in a 24-foot box truck.

The store owners mentioned their increased costs due to packaging requirements. A-50 vendors sell at least some, if not all, of their produce prepackaged, priced most commonly in 50-cent increments up to $3 so customers can easily determine how many items they can purchase for the $6 and $10 vouchers. Three of the five stores do some or all of their own packaging, while two stores purchase products prepacked by distributors or processors.

After the introduction of F&V vouchers, some A-50 vendors experienced increased costs due to packaging requirements; some or all of their produce is sold prepackaged.

All the store owners stressed the importance of good quality and reasonably priced produce when competing for customers, because WIC shoppers are not likely to visit more than one store to spend their vouchers. Four of the five said that they priced their produce very competitively to attract customers and give them the greatest variety possible for their F&V vouchers. Most of the store owners noted that high-quality, reasonably priced produce brings in new non-WIC customers. One owner estimated that 10% to 20% of produce sales are to non-WIC customers. Another now stocks specialty produce items, such as plantains and yucca, requested by the neighborhood's non-WIC customers who have started shopping at the store. Another owner mentioned that pricing the produce aggressively encouraged WIC customers to spend more, using the F&V vouchers for some of their purchases.

These interviews revealed several reasons why it was unlikely that the store owners would purchase a few select product items for their stores from small farms. Four of the five store owners identified distributors’ lower prices, broad product mix and preference for prepackaged produce as reasons for using produce distributors. The fifth owner found it more cost effective to purchase produce direct from farms and produce terminals, which growers often utilize if they have excess produce that they need to sell quickly at reduced prices.

Survey of produce distributors

Most A-50 vendors do not have the facilities, staffing, expertise or volume to source their produce direct from packer/shippers or processors. Instead, they rely on regional produce distributors, many of which sought out the larger A-50 chains as customers when the F&V vouchers were introduced.

We interviewed two large regional produce distributors about their experiences supplying A-50 vendors. They did not make any major capital improvements when they took on the vendors as customers. However, they did provide merchandising guidance and limited handling advice to store chain management and staff. One distributor sold refrigeration and display units to the store chains; in some cases, the distributor paid for part or all of the cost of the equipment. These distributors reported that their sales to A-50 vendors represented between 15% and 20% of their firm's revenues.

One distributor noted the low volumes of produce to some A-50 vendors were too costly to deliver in 40,000-pound trailers; consequently, deliveries are made to only some of the stores, and the store chain uses its own trucks to distribute the produce to its smaller stores. The other distributor determined that the sales volumes of some A-50 vendor accounts were too small to be profitable, so these accounts were relinquished to a smaller distributor.

Both distributors commented that the A-50 vendors they supply face stiff price competition from Walmart and the box stores, so small growers interested in supplying produce to the distributors must also have competitive prices. Both distributors require their suppliers to have food safety certification from a third party and liability insurance. One distributor requires its suppliers to provide prepackaged products to be sold at specific prices; the other distributor does the prepacking.

Our interviews with produce distributors confirmed the small farms’ inability to compete with them on price, product mix and services when supplying the WIC A-50 vendors. Many large regional distributors were ready to supply A-50 vendors when the F&V voucher program was implemented, but one of these distributors found that sales to some A-50 vendors were too low to be profitable and relinquished these accounts to a smaller distributor.

WIC vouchers in farmers markets

In 2010, the California WIC program piloted the acceptance of WIC F&V vouchers at a small number of certified farmers markets. However, grower participation in California in the current F&V voucher program has been low. The first farmers market authorization occurred in May 2010. As of March 4, 2015, there were only 31 farmers markets and 149 growers authorized for F&V vouchers, compared with 371 farmers markets and 1,018 farms authorized for USDA Farmers Market Nutrition Program (FMNP) vouchers in California (CDPH 2015). The total value of WIC F&V vouchers redeemed at farmers markets in California during 2011 and 2012 (table 1) represented less than 0.05% of the total WIC F&V redemptions.

Farmers Market Nutrition Program vouchers are issued once a year for use between May and November at WIC-approved certified farmers markets.

USDA's Food and Nutrition Service introduced FMNP vouchers in the 1990s, enabling growers to provide fresh, nutritious and locally grown fruits and vegetables to WIC families at farmers markets. Each eligible family receives $20 in vouchers once a year to redeem between May and November for fresh fruits, vegetables and cut herbs at WIC-approved certified farmers markets in California. In 2010, program participants included 149,200 WIC families, 1,100 certified growers and 430 certified farmers markets (CDPH 2014).

The FMNP is popular with most small direct-marketing growers because the vouchers can be redeemed only at certified farmers markets, thus increasing the markets’ customer counts and raising the growers’ revenues. Redemptions of FMNP vouchers increased from 57.2% in 2005 to 66.2% in 2012 (McDonnell et al. 2014) and 68% in 2014 (CDPH 2015). Transportation to farmers markets was commonly identified by WIC clientele as a barrier to participation in the FMNP. Some local WIC agencies have set up new farmers markets close to the offices where they distribute vouchers. At many California farmers markets in low-income neighborhoods, nonprofit organizations and private funders provide matching funds that allow WIC shoppers (as well as food stamp and Social Security recipients) to double the value of their vouchers (Roots of Change 2012); this has contributed significantly to the program's success.

To be able to accept F&V or FMNP vouchers, both the grower and the market where he or she is selling must be authorized by California's WIC program; the authorization requirements are essentially the same for both voucher programs. However, the F&V vouchers are more difficult for the grower to redeem than the FMNP vouchers. The grower must check the F&V voucher to ensure that it is being used within the required 30-day redemption period; FMNP vouchers are valid for 6 months. Tessman and Fisher (2009) noted that California is one of only two states that require growers to call in the numbers on each redeemed F&V voucher. Growers must deposit the vouchers in the bank within 45 days of the “first day to use” indicated on the voucher. Banks may charge a fee for depositing a large number of vouchers. The vouchers can get damaged if it is raining, and then they can be rejected by banks.

Using F&V vouchers at farmers markets is also problematic from the WIC client's perspective. Since the entire F&V voucher must be spent at one time, a grocery store with a wide selection of produce is more appealing than an individual grower at a farmers market. Additionally, grocery stores have extended hours of operation and are more convenient to shop at than farmers markets.

Occidental's farm-to-WIC program

Occidental College's Urban and Environmental Policy Institute (UEPI) initiated a farm-to-WIC program in 2009 to improve the health and vitality of local communities. Similar to the UCCE pilot project, it strives to provide WIC families with high-quality seasonal produce while expanding market opportunities for small local farms. Starting with four participating A-50 stores in Los Angeles, it now includes 12 flagship stores in Los Angeles County selling produce from a dozen local growers (Y. Zeltser, unpublished data). Its purchases from small local farms in the first 3 years totaled over $500,000. Two of the store partners, Mother's Nutritional Center and Prime Time Nutrition, each operate more than 50 A-50 stores in California; they are the two largest A-50 store chains in California. Fewer than 30% of Prime Time Nutrition's stores are in Southern California; all the Mother's stores are located there.

UEPI's program initially involved sourcing one local product each month — a Harvest of the Month model. The turnaround period proved too short for stores struggling with packaging and handling issues; it was also less convenient for growers, who do not want to sell their product for just 1 month. Thus, the program shifted to a seasonal model, which limits the number of items but provides more opportunity for store employees and customers to become familiar with the products.

The success of UEPI's program can be partially attributed to its unusual product offerings from local farms, including Cuyama Crimson Gold crabapples and Ojai Pixie tangerines, both of which are only about 1 inch in diameter. Many of the products offered in UEPI's program are too small to be desirable to conventional grocery stores, but they are a perfect snack size for young eaters. These small fruit, along with UEPI's marketing program, have helped its A-50 store chain partners differentiate themselves from large retailer competitors. Growers benefit financially from UEPI's program because it provides them with a niche market that probably would not exist otherwise.

Supply chain barriers

The UCCE pilot project demonstrated that small farms face several barriers to gaining access to the WIC produce supply chain and providing WIC clients with F&V vouchers for local produce. These barriers are particularly evident when considered with the transitions the A-50 WIC store owners have had to make and their relationships with produce distributors; they are evident also in the successes of the UEPI project and FMNP voucher program. The A-50 vendors are competing with established large retailers that operate with very small margins. Small farms lack economies of scale in production; therefore, they cannot provide competitive pricing when selling direct to A-50 vendors or through produce distributors.

Individual small farms offering limited volumes of high-quality product are not set up to meet the demands of these A-50 vendors.

ALBA Organics succeeded in making a few sales transactions with an A-50 store chain, but ALBA Organics had several assets that individual small growers usually lack: familiarity with produce industry standards; a cooler facility and equipment to store and load the buyer's trucks; and third-party food safety certification and liability insurance (Berkenkamp 2011; Feenstra et al. 2011; Tropp and Barham 2008). Significantly, the sales occurred at peak season when prices were low and product supply exceeded what the growers could sell directly themselves.

The success of UEPI's program is similarly attributable to a particular set of circumstances, especially the expertise and facilities provided by its produce consultant, who helped develop a streamlined process for placing orders and communicated quality or delivery problems between the vendors and growers. The program involves a limited selection of products that are well suited to young children. UEPI's A-50 store chain partners are small customers in the wholesale produce market compared with their large retail chain competitors. As they strive to aggregate their purchasing to gain market power and improve their distribution efficiency, these A-50 vendors need high-quality produce, a steady supply and competitive prices. Individual small farms offering limited volumes of high-quality product are not set up to meet the demands of these A-50 vendors. However, they could adapt UEPI's small fruit program — sort out small fruit, bag them and offer them as special kid-sized packs — to other A-50 vendors, farmers markets or farm stands.

Farmers markets participating in the FMNP provide small growers a means of entry into the WIC produce supply chain, but few WIC shoppers are using their F&V vouchers at farmers markets. FMNP redemptions increased significantly when private matching funds essentially doubled the vouchers’ value. If USDA could raise the value of the FMNP vouchers, WIC clients could be expected to increase their purchases at farmers markets. However, reductions in congressional allocations for food security programs reflected in the 2014 Farm Bill make increased funding for FMNP vouchers unlikely. Since most WIC shoppers tend to spend their vouchers in one place, increasing redemptions of F&V vouchers at farmers markets may be a slow process. However, USDA is implementing an electronic benefit program for WIC (USDA FNS 2013), which could make the payment process less onerous for growers and increase F&V voucher use at farmers markets.

The results of the pilot project and the very low redemption rate of WIC F&V vouchers at farmers markets in California raise questions about the role of small farms in food security programs. Should their participation in these programs be a priority, and, if so, how can their ability to participate best be enhanced? Can small farms collaborate or organize themselves to provide reliable supplies of produce to local A-50 vendors, food banks, schools and businesses and also enhance their profitability? These questions raise many policy issues that need to be addressed by policymakers, and they warrant further research on the marketing challenges and constraints faced by small growers.