Posts Tagged: history

Los Angeles and the “Orange Empire”

An interesting book called “Orange Empire: California and the Fruits of Eden” by Douglas Cazaux Sackman tells the story of how oranges went from being an occasional treat to a mainstream part of the American diet. In fact, Los Angeles was once the center of the “Orange Empire” which developed into a massive industry in California.

Oranges were brought by the Spanish as they settled the missions, and the first sizable grove in Alta California was planted at the San Gabriel Mission, near Los Angeles, around 1804. Oranges were grown on a very limited scale until a frontiersman and entrepreneur named William Wolfskill decided to try growing oranges commercially, using seedlings from the Mission. His initial two-acre orchard was planted in 1841 in what is now downtown Los Angeles. During the Gold Rush, he was able to ship his citrus crop north to miners who were willing to pay a premium to protect themselves from scurvy.

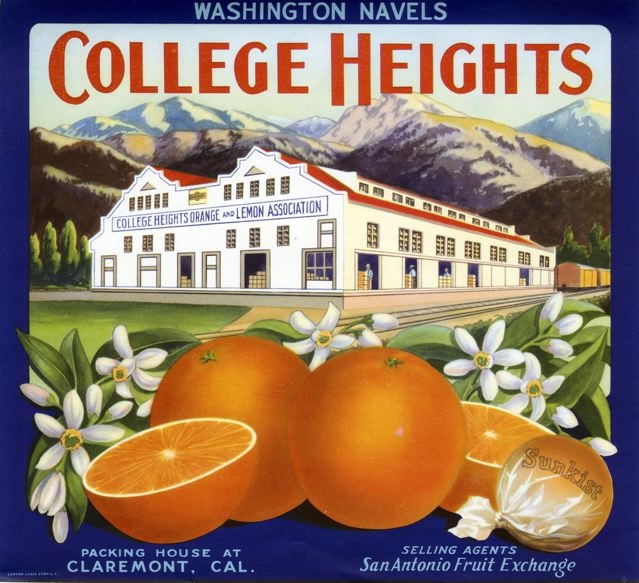

The citrus industry in Southern California grew slowly at first, then really took off in the 1870s due to two innovations. First, a family in Riverside obtained two trees of an orange variety from Brazil. The fruit from these trees was larger, sweeter and easier to peel. This variety, which came to be known as the Washington Navel, created a surge of interest in growing oranges. In the same decade, the transcontinental railroad system connected to Los Angeles, and the very first railcar load of oranges, from the Wolfskill orchard, was shipped east in 1877. In the late 1880s, with the advent of refrigerated rail shipping, the growing citrus industry got another boost. Many new growers entered the citrus farming business, and numerous towns along the foothills of the Los Angeles basin were formed as the industry grew up in those areas.

“Centered on the Los Angeles basin, a vast citrus landscape was coming into being,” said Sackman (p.42). “In 1870, only 30,000 orange trees were growing in the state. Twenty years later, 1.1 million trees were producing fruit." By 1893, local citrus growers had organized themselves into the Southern California Fruit Growers Exchange, which later became known as Sunkist. Sunkist was instrumental in driving the demand for oranges, promoting oranges and orange juice as health aids, with national advertising campaigns beginning in 1907. Sunkist advertisements, along with colorful orange crate labels, helped to brand Los Angeles and Southern California as a new Eden, the land of sunshine and good health. This image helped to drive migration from to Southern California for many years.

Commercial citrus production in Los Angeles County began to decline after World War II, as orchards were rapidly sacrificed to the growing, sprawling suburbs of the Los Angeles basin. As recently as 1970, there were still more than 50,000 acres of citrus in the county; but today, most orange trees in Los Angeles are in backyards rather than in groves.

The citrus industry, still critical to California’s agricultural economy, has long since moved to other counties and other parts of the state. While there is no longer an “Orange Empire” here in Los Angeles, oranges are still a treat, especially if grown in our own backyards. As I prepare for the holidays, I know that today, an orange in a stocking might not be as special as it once was. But to pluck an orange off a tree, on a 75 degree day in December, still makes Los Angeles seem like Eden to a former Midwesterner like me.

Will work for food

The Los Angeles Times today ran a compelling photo in its blog "Framework," which shares intriguing news images of the past, showing men collecting vegetables in payment for labor during the Great Depression. For information on such cooperatives, Framework directed readers to a blog post written by the director of UC Cooperative Extension in Los Angeles County, Rachel Surls, in June 2010.

Surls reported that many farmers were unable to harvest produce because they couldn’t afford labor, and enormous quantities of food were left in the fields as people went hungry. One response of Los Angeles County residents was to organize into “self-help cooperatives." Self-help cooperatives were based on bartering labor for goods, for example, harvesting farmer’s crops for a share of the harvest.

Cooperatives helped unemployed people who preferred to work rather than accept public assistance. (Photo: Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley)

School gardens: Important in the past...and the future

In 1909, Ventura schoolteacher Zilda M. Rogers wrote to the Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of California, Berkeley, then the flagship agricultural campus for California’s land grant institution, and a primary proponent and provider of garden education resources for schoolteachers. Rogers wrote in some detail about how her school garden work had progressed, what the successes and failures were, how the children were responding to the opportunity to garden, how her relationship with the children had changed as a result of the garden work, and what she saw as potential for the future.

“With the love of the school garden has grown the desire for a home garden and some of their plots at home are very good. . . . Since commencing the garden work the children have become better companions and friend . . . and to feel that there is a right way of doing everything. . . . It is our garden. . . . We try to carry that spirit into our schoolroom.”

More than 100 years after Rogers wrote those words, school gardens have continued to be cherished in the public school system in which she worked. The Ventura Unified School District has developed a nationally recognized model that links school gardening, nutrition education and a farm-to-school lunch program featuring many locally sourced fruits and vegetables for its 17,000 public school students.

The University of California took note of the success that educators like Rogers were experiencing with school gardens. Being certain to include the words written by her, the University of California published Circular No. 46, which offered information about how to build school garden programs. School gardens were to be an integral part of primary schooling. As the circular declared, “The school garden has come to stay.”

School gardens had been used in parts of Europe as early as 1811, and mention of their value preceded that by nearly two centuries. Philosophers and educational reformers such as John Amos Comenius and Jean-Jacques Rousseau discussed the importance of nature in the education of children; Comenius mentioned gardens specifically.

The use and purpose of school gardens was multifold; gardens provided a place where youth could learn natural sciences (including agriculture) and also acquire vocational skills. Indeed, the very multiplicity of uses and purposes for gardens made it difficult for gardening proponents to firmly anchor gardening in the educational framework and a school’s curriculum. It still does.

The founder of the kindergarten movement, Friedrich Froebel, used gardens as an educational tool. Froebel was influenced by Swiss educational reformer Johann Pestalozzi, who saw a need for balance in education, a balance that incorporated “hands, heart, and head,” words and ideas that would be incorporated nearly two centuries later into the mission of the United States Department of Agriculture’s 4-H youth development program. (These words still guide the work of the University of California’s 4-H program). Educational leaders such as Liberty Hyde Bailey and John Dewey fused ideas of nature study and experiential education with gardening.

Perhaps one of the earliest school garden programs in the United States was developed in 1891, at the George Putnam School in Roxbury, Mass. (Today, the nationally recognized food project also teaches youth about gardening and urban agriculture in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston). Like others interested in gardening, Henry Lincoln Clapp, who was affiliated with the George Putnam School, traveled to Europe for inspiration. After traveling to Europe and visiting school gardens there, he partnered with the Massachusetts Horticultural Society to create the garden at Putnam; the model was replicated around the state. It was followed in relatively short order by other efforts, including a well-known garden program in New York City: the DeWitt Clinton Farm School.

Gardening became nearly a national craze during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and “school” gardens enjoyed immense popularity. The United States Department of Agriculture estimated that there were more than 75,000 school gardens by 1906. As their popularity soared, advocates busily supplied a body of literature about school gardening and agricultural education.

One book argued that school gardens were not a “new phase of education,” but rather, an “old one” that was gaining merit for its ability to accomplish a wide variety of needs. School gardens were a way to reconnect urbanized American youth with their agrarian, producer heritage, the Jeffersonian idea of the sturdy yeoman farmer. One author argued for the importance of gardening education and nature study for both urban and rural youth, for “sociological and economic” reasons.

One important reason to garden with urban youth was to teach “children to become producers as well as consumers,” and for the possibility “of turning the tide of population toward the country, thus relieving the crowded conditions of the city.” Other reformers echoed this idea, including Jacob Riis, who said, “The children as well as the grown people were ‘inspired to greater industry and self-dependence.’ They faced about and looked away from the slum toward the country.” It’s now more than a century later, the average American farmer is in his/her late 50s, and the need to reconnect a new generation of youth to the land seems even more compelling. Could the school gardens of today provide the farmers of tomorrow?

The school garden movement received a huge boost during World War I, when the Federal Bureau of Education introduced the United States School Garden Army. During the interwar years and the Great Depression, youth participated in relief gardening. During World War II, a second Victory Garden program swept the nation, but after that, school garden efforts became the exception, not the norm.

The 1970s environmental movement brought renewed interest to the idea of school and youth gardening, and another period of intense growth began in the early 1990s. Interest in farm-to-school has continued to breathe life into the school garden movement, and some states, notably California, have developed legislation to encourage school gardens. (Under the tenure of State Education superintendent Delaine Eastin, a Garden in Every School program was begun. Under Jack O’Connell’s tenure, Assembly Bill 1535, which funded school gardens, was approved).

We should all take note of the tagline for the U.S. government’s youth gardening program in World War I: “A Garden for Every Child. Every Child in a Garden.” Wouldn’t this be a great idea today? With the cuts in school funding, increased classroom size and other challenges, some school garden programs are facing real challenges. They deserve our support, not only in practice (volunteer!) but also by our advocacy for public policies that support youth gardening work in school and community settings. Why not advocate for a nationally mandated curriculum that promotes food systems education in American public schools, something like “Race to the Crop”?

Some of the best models for school gardens lie in our past. But the real potential of school gardens to reduce obesity, encourage a healthy lifestyle, reconnect youth with the food system and to build healthier, vibrant communities is something we can realize today . . . and is something that should be an important concern of our national public policy.

A note to readers: Google Books contains copies of two important books in the school gardening literature of the Progressive Era, (Miller and Greene’s), as well as numerous other Progressive era books pertaining to gardening and agricultural education. To learn more about the United States School Garden Army’s efforts during WWI (a GREAT model for a national curriculum today!), visit the UC Victory Grower website.

Students record plant growth in a school garden.

UC the midwife in birth of California Farm Bureau

The California Farm Bureau Federation is marking its 90th anniversary next year with an article in the current issue of AgAlert that traces the organization's origins and provides historical anecdotes. In the article, UC Cooperative Extension gets credit for being the "midwife" when the statewide organization was born in 1919.

Extension was created by the federal government in 1914. Before academic staff would be assigned to a county, the service was required to establish a farm organization to channel information from advisors and specialists to farmers and their families.

A county Farm Bureau representing at least 20 percent of the farmers in the county had to be operating before a farm advisor could be appointed for the county, according to the AgAlert article, written by the publication's executive editor, Steve Adler.

The first California county to qualify was Humboldt, which formed its Farm Bureau in 1913. The following year, Yolo, San Joaquin and San Diego counties founded their Farm Bureaus.

The article quoted a 1917 circular written by the founder of California's Agricultural Extension Service, B.H. Crocheron. Crocheron envisioned the county Farm Bureau acting as "a sort of rural chamber of commerce and ... the guardian of rural affairs. It can take the lead in agitation for good roads, for better schools, and for cheaper methods of buying and selling."

"Perhaps the Farm Bureau can help to buy cheaper and better seeds, can help to boost the local socials, can encourage the faltering school teacher, can get out and talk for good roads--but its first and surest function is to increase the local knowledge of agricultural fact," Adler further quoted Crocheron.

In time it became clear that the Farm Bureau should pursue a broader agenda, according to the article.

"Because the university could not participate in those extra activities, organizers decided to separate the Farm Bureau from the extension service. That was accomplished with the birth of CFBF on Oct. 23, 1919, when its constitution and bylaws were officially adopted," Adler wrote.