- Author: Pamela Kan-Rice

UC Berkeley professor Barbara Allen-Diaz, associate vice president of Agriculture and Natural Resources, was appointed today (Sept. 15) by the Board of Regents to a term position as head of the university’s statewide agricultural and natural resources programs.

As UC systemwide vice president for Agriculture and Natural Resources (ANR), Allen-Diaz will lead the university’s research and outreach activities in food systems, environmental sciences, family and consumer sciences, forestry, community development, 4-H youth development and related areas. The appointment is effective for up to three years, beginning October 1, 2011.

“For more than 140 years, UC has provided California farmers the research and new technology they need to compete in global markets,” said UC President Mark G. Yudof. “Together, we have developed new crops varieties and some of the most progressive and environmentally friendly farming practices to produce an abundant and safe supply of food. Under the leadership of Barbara Allen-Diaz, ANR will continue its legacy of working within California communities to address new challenges.”

ANR programs, including Cooperative Extension and the Agricultural Experiment Station, are located on UC’s Berkeley, Davis and Riverside campuses, with nine research and extension centers and more than 50 county offices throughout the state, with nearly 1,000 Agricultural Experiment Station faculty, Cooperative Extension specialists and Cooperative Extension advisors.

“I am deeply honored to be selected as vice president for Agriculture and Natural Resources,” said Allen-Diaz. “I am privileged to work with incredibly dedicated, hard-working people who possess exceptional expertise and a passion to find solutions to the most pressing problems facing California agriculture, natural resources and our youth.”

The first woman to lead UC’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Allen-Diaz succeeds Daniel M. Dooley, who was appointed in January 2008. In November 2008, Dooley agreed to take on additional responsibilities as senior vice president for External Affairs and he has served since then in both roles. Given the increasing demands of the two roles, it is no longer feasible for one individual to cover both positions.

As Dooley resigns his position as vice president-Agriculture and Natural Resources on October 1, Allen-Diaz will succeed him as vice president, reporting directly to the provost and executive vice president-Academic Affairs.

In addition to his title as senior vice president for external relations, Dooley will be named senior advisor to the President on Agriculture and Natural Resources and will be available to advise Allen-Diaz, Provost Lawrence Pitts and President Yudof on issues related to agriculture and natural resources and the strategic direction of ANR.

Allen-Diaz is an effective and seasoned leader in the Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, where she has served as associate vice president-Academic Programs and Strategic Initiatives since 2009 and as assistant vice president–programs since 2007. She is currently on leave from her position as a tenured faculty member in the College of Natural Resources on the Berkeley campus, where she has worked since 1986. She also holds the prestigious Russell Rustici Chair in Rangeland Management.

“I am very excited about Barbara stepping into this role,” said Dooley. “As a member of a farming family, I have a personal investment in ANR and I know she cares deeply about the organization. I respect her as a scientist and have confidence in her capability to lead ANR.”

Allen-Diaz was among 2,000 scientists recognized for their work on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), when the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded jointly to the IPCC and Vice President Al Gore in 2007. Allen-Diaz's contributions focused on the effects of climate change on rangeland species and landscapes. She has authored more than 160 research articles and presentations and is an active participant in her professional society; she has served on its board of directors and on various government panels.

Allen-Diaz will receive an annual salary of $280,000, along with the following additional items university policy: standard pension and health and welfare benefits and standard senior management benefits, including Senior Manager Life Insurance, Executive Business Travel Insurance and Executive Salary Continuation for Disability, and use of administrative funds for official entertainment and other purposes permitted by university policy.

Allen-Diaz earned a B.A. in anthropology, an M.S. in range management and a Ph.D. in wildland resource sciences, all from UC Berkeley.

- Posted By: Jeannette E. Warnert

- Written by: Kathy Keatley Garvey, (530) 754-6894, kegarvey@ucdavis.edu

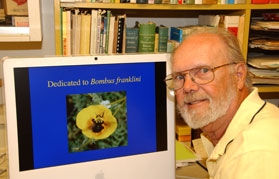

A petition spearheaded by Thorp and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation to list Franklin’s bumble bee under the National Endangered Species Act has moved to the next step in the process, the 12-month review period. This may lead to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) listing it as “endangered” and providing protective status.

The bad news: Thorp hasn’t seen Franklin’s bumble bee since 2006.

“I am still hopeful that Franklin’s bumble bee is still out there somewhere,” said Thorp, emeritus professor of entomology. “Over the last 13 years I have watched the populations of this bumble bee decline precipitously. My hope is this species can recover before it is too late."

Thorp researches the declining population of Franklin’s bumble bee, Bombus franklini (Frison), found only in a narrow range of southern Oregon and northern California. Its range, a 13,300-square-mile area confined to Siskiyou and Trinity counties in California; and Jackson, Douglas and Josephine counties in Oregon, is thought to be the smallest of any other bumble bee in North America and the world.

Thorp’s surveys, conducted since 1998 clearly show the declining population. Sightings decreased from 94 in 1998 to 20 in 1999 to 9 in 2000 to one in 2001. Sightings increased slightly to 20 in 2002, but dropped to three in 2003. Thorp saw none in 2004 and 2005; one in 2006; and none since.

“My experience with the Western bumble bee (B. occidentalis) indicates that populations can remain ‘under the radar’ for long periods of time when their numbers are low,” he said. Thorp did not see the Western bumble bee between 2002-2008, but now, although sightings are rare, they are “consistently encountered.”

This year Thorp surveyed the bumble bee's historic sites in southern Oregon and northern California on five separate trips of several days each: two in June and one each in July, August and September. "Flowering and bumble bee phenology were pushed back about a month this year due to our cold wet spring," he said. " I managed to see and photograph workers of B. occidentalis at two sites on my August trip. I had hoped to see males and even a Franklin’s on my last visit in September, but alas no luck."

"However, flowering was more like mid-August and lots of other species of worker bumble bees were still foraging," he noted. "Males and new queens were also on the wing. The new queens will mate and hibernate to emerge and produce new colonies next year. The old queens and the rest of this year's colony members will die out soon, as this season winds to a close."

Thorp and the Xerces Society petitioned USFWS on June 23, 2010 for endangered status for the bumble bee. Today (Sept. 13) USFWS announced “Based on our review, we find that the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that listing this species may be warranted. Therefore, with publication of this notice we are initiating a review of the status of the species to determine if listing the Franklin’s bumble bee is warranted that Franklin's bumble bee may warrant protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.”

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the world’s oldest and largest global environmental network, named Franklin’s bumble bee “Species of the Day” on Oct. 21, 2010. IUCN placed it on the “Red List of Threatened Species” and classified it as “critically endangered” and in “imminent danger of extinction.”

Franklin's bumble bee, mostly black, has distinctive yellow markings on the front of its thorax and top of its head, Thorp said. It has a solid black abdomen with just a touch of white at the tip, and an inverted U-shaped design between its wing bases.

“This bumble bee is partly at risk because of its very small range of distribution,” he said. “Adverse effects within this narrow range can have a much greater effect on it than on more widespread bumble bees.”

If it’s given protective status, this could “stimulate research into the probable causes of its decline,” said Thorp, an active member of The Xerces Society. “This may not only lead to its recovery, but also help us better understand environmental threats to pollinators and how to prevent them in future. This petition also serves as a wake-up call to the importance of pollinators and the need to provide protections from the various threats to the health of their populations.”

Thorp hypothesizes that the decline of the subgenus Bombus (including B. franklini and its closely related B. occidentalis, and two eastern species B. affinis and B. terricola) is linked to an exotic disease (or diseases) associated with the trafficking of commercially produced bumble bees for pollination of greenhouse tomatoes.

Other threats may include pesticides, climate change and competition with nonnative bees, according to the Xerces Society executive director Scott Hoffman Black. Said Sarina Jepson, endangered species program director at the Xerces Society: "Bumble bees play a critical role in ecosystems as pollinators of wildflowers, as well as many crops. We hope that the service will ultimately provide Endangered Species Act protection to this important pollinator."

Named in 1921 for Henry J. Franklin, who monographed the bumble bees of North and South America in 1912-13, Franklin’s bumble bee frequents California poppies, lupines, vetch, wild roses, blackberries, clover, sweet peas, horsemint and mountain penny royal during its flight season, from mid-May through September. It collects pollen primarily from lupines and poppies and gathers nectar mainly from mints.

According to a Xerces Society press release, bumble bees are declining throughout the world.

Researchers in Britain and the Netherlands have “noticed a decline in the abundance of certain plants where multiple bee species have also declined. For many crops, such as greenhouse tomatoes, blueberries and cranberries, bumble bees are better pollinators than honey bees, and some species are produced commercially for their use in pollination. ”

Last October Thorp received a 2010-11 Edward A. Dickson Emeriti Professorship Award, from UC Davis to support his research on the critically imperiled bumble bee. The objectives of Thorp’s research funded by the Dickson grant are to:

- Collect bumble bees for disease studies at the University of Illinois with emphasis on B. franklini (where and when appropriate so as not to hinder population recovery) and B. occidentalis and potential reservoir species known to co-occur with them, all within the historic range of B. franklini.

- Survey for B. franklini and B. occidentalis with emphasis on B. franklini historical sites.

- Include observations on population abundance of other species of bumble bees at monitoring sites for comparison with the two target species.

- Monitor floral visitation and track any individuals of B. franklini and/or B. occidentalis to determine their foraging behavior, subset of overall habitat used, nest site locations, and acceptance of trap-nest boxes.

Thorp, a fellow of the California Academy of Sciences, teaches “The Bee Course” every summer for the American Museum of Natural History of New York at its field station in Arizona.

(Editor's Note: The Xerces Society contributed to this news release. See UC Davis Department of Entomology website at http://entomology.ucdavis.edu/news/franklinbumblebee.html for larger version of Franklin's bumble bee)

- Posted By: Jeannette E. Warnert

- Written by: Diane Nelson, (530) 752-1969, denelson@ucdavis.edu

The stripe rust disease of wheat caused by the highly specialized fungal pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici has been responsible for recurrent episodes of large yield losses and economic hardship among grain-based agricultural societies for centuries. Current epidemics of new aggressive races of Puccinia striiformis that appear after the year 2000 pose significant threats to food security worldwide and, in particular, in developing countries in Africa and central Asia. In spite of its economic importance, the Puccinia striiformis genomic sequence is not currently available.

In order to get access to the genes of this pathogen, a team of researchers – including Professor Jorge Dubcovsky (also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute researcher) and Professor Richard Michelmore, director of the UC Davis Genome Center, Project Scientist Dario Cantu and Manjula Govindarajulu, a postdoctoral researcher in Michelmore’s lab - used cutting-edge technology to rapidly sequence a large portion of the genome of one of the Puccinia striiformis more virulent and aggressive races. They assembled long stretches of the Puccinia striiformis genome and established a preliminary automatic annotation of its genes, with a special focus on those likely to be involved in pathogenicity.

This information is available in the open-access article published by the Public Library of Science and made publically available through the National Center of Biotechnology information and a dedicated web page.

“This shotgun sequence assembly does not substitute for the need of a complete and annotated Puccinia striiformis genome, but it provides immediate access to a large proportion, more than about 88 percent, of the genes from this pathogen,” said Cantu. “This public information has the potential to accelerate a new wave of studies to determine the mechanisms used by this pathogen to infect wheat, and hopefully to reduce current yield loses caused by this pathogen.”

These researchers, in collaboration with others at the John Innes Institute in the UK, are currently sequencing new and old races of Puccinia striiformis to investigate their differences in virulence and aggressiveness.

This project was supported in part by funds provided through a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the National Research Initiative Competitive Grants from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

- Posted By: Jeannette E. Warnert

- Written by: Brenda Dawson, (530) 752-7779, bldawson@ucdavis.edu

The talk, along with introductions, Q&A and light refreshments, will be 4 – 6 p.m. at the Rominger West Winery, 4602 Second St. in Davis. Tickets are $10, and reservations are available online at http://ucanr.org/slowmoney.

Slow Money is a national network dedicated to investing in local food and agricultural enterprises.

“We often hear about ‘voting with your dollar’ when it comes to supporting small-scale farmers and local food,” said Shermain Hardesty, Cooperative Extension economist in the UC Davis Department of Agricultural and Resources Economics. “Shopping at a farmers market or becoming a CSA member are ways to support small-scale farms as a consumer, but Slow Money can be a way to invest in them.”

One local venture which has sought funding through Slow Money is the Capay Valley Farm Shop, a collaborative of 30 farms and ranches who together offer a CSA to institutions and corporations.

“Through Slow Money, we’re reaching investors who share our values, who believe that community food systems are a great investment for the health of communities and for the planet,” said Thomas Nelson, president of Capay Valley Farm Shop.

After presenting at an entrepreneur showcase this summer, the Capay Valley Farm Shop is working with a group of interested investors through Slow Money.

Another agricultural venture, Soul Food Farm in Vacaville, has also worked with Slow Money investors, receiving approximately $40,000 in loans.

“This model is another way that entrepreneurs in sustainable agriculture and community food systems can seek funding—especially when conventional sources such as venture capital, the Farm Credit System or commercial banks may not be an option,” Hardesty said.

The event will include a brief introduction to current UC Davis research on values-based food systems by Hardesty and Gail Feenstra, of the Agricultural Sustainability Institute. Values-based food systems create relationships between growers, funders, distributors, consumers and others based on shared values. Their project is working to identify bottlenecks—including access to capital—in the development of these values-based food supply chains, with an eye toward the enhancing the prosperity of smaller producers through networks that support environmental and social sustainability. This research is part of a USDA-funded, multi-state project, along with researchers at Colorado State University and Portland State University.

The event is sponsored by the Davis Food Co-op, Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op and the Giannini Foundation.

More details and ticket reservations for this event are available at http://ucanr.org/slowmoney.

- Posted By: Jeannette E. Warnert

- Written by: Bettye Miller, (951) 827-7847, bettye.miller@ucr.edu

A catastrophic infestation of the goldspotted oak borer, which has killed more than 80,000 oak trees in San Diego County in the last decade, might be contained by controlling the movement of oak firewood from that region, according to researchers at UC Riverside.

“This may be the biggest oak mortality event since the Pleistocene (12,000 years ago),” said Tom Scott, a natural resource specialist. “If we can keep firewood from moving out of the region, we may be able to stop one of the biggest invasive pests to reach California in a long time.”

A cadre of UC researchers is leading the effort to assess and control the unprecedented infestation, in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service. Scott and others are working to identify where the infestation began, how it is spreading through southern California’s oak woodlands, and what trees might be resistant. In October 2010 Scott and other UCR researchers received $635,000 of a $1.5 million grant of federal stimulus money awarded to study the goldspotted oak borer and sudden oak death.

The goldspotted oak borer (Agrilus auroguttatus), which is native to Arizona but not California, likely traveled across the desert in a load of infested firewood, possibly as early as the mid-1990s, Scott said. Researchers have confirmed the presence of the beetle as early as 2000 near the towns of Descanso and Guatay, where nearly every oak tree is infested.

The half-inch-long beetle attacks mature coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), California black oaks (Quercus kelloggii) and canyon live oaks (Quercus chrysolepis). Female beetles lay eggs in cracks and crevices of oak bark, and the larvae burrow into the cambium of the tree to feed, irreparably damaging the water- and food-conducting tissues and ultimately killing the tree. Adult beetles bore out through the bark, leaving a D-shaped hole when they exit.

Scott and Kevin Turner, goldspotted oak borer coordinator for UC Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) at UCR, said that field studies in San Diego County in the last six months point strongly to the transportation of infested oak firewood as the source of the invasion that threatens 10 million acres of red oak woodlands in California.

Outbreaks have been found 20 miles from the infestation area, implicating firewood as the most likely reason for the beetle infestation leap-frogging miles of healthy oak woodlands to end up in places like La Jolla. In contrast, communities that harvest their own trees for firewood have remained relatively beetle-free, even as adjacent areas suffer unprecedented rates of oak mortality. Both examples support the growing conviction that the movement of infested firewood is the primary means by which the beetles are spreading, Scott said.

California’s coast live oaks, black oaks and canyon live oaks seem to have no resistance to the goldspotted oak borer and, so far, no natural enemies of the beetle have been found in the state.

The devastation can be measured in costs to communities and property owners for tree removal, the loss of recreation areas and wildlife habitat, lower property values and greater risk of wildfires. The three oaks under attack may be the single most important trees used by wildlife for food and cover in California forests and rangelands.

Most of the dead and dying trees are massive, with trunks 5 and 6 feet in diameter, and are 150 to 250 years old. The cost of removing one infested tree next to a home or in a campground can range from $700 to $10,000. The cost of removing dead and dying trees in San Diego County alone could run into the tens of millions of dollars. In Ohio, which has experienced similar losses from the emerald ash borer, several small cities went bankrupt because of tree removal costs associated with that beetle, Scott said.

So many oaks have died in the Burnt Rancheria campground on the Cleveland National Forest – a favorite spot for campers who favored the shade of a dense canopy of coast live oaks – that the Forest Service has had to erect shade structures. Other state and county parks in the region have suffered equally devastating losses.

Turner said an Early Warning System of community volunteers launched in San Diego County now includes representatives from every southern California county as far north as Ventura. Those volunteers are trained to monitor the health of oak trees in their communities and report any unusual changes.

At the same time, a network of UC Cooperative Extension, ANR, U.S. Forest Service and other agencies in the region is working with woodcutters, arborists and consumers to discourage the sale and transportation of infested wood. Wood that is bark-free or that has dried and cured for at least one year is generally safe to transport, Scott said. This relatively small change in firewood-handling methods could save a statewide resource without jeopardizing the firewood industry, he said.

Local, state and federal agencies recognize that firewood production is one of the least-regulated industries in California, and view UC Cooperative Extension education as the best means of stopping goldspotted oak borer movement in firewood.

“Quarantines don’t work, but enlightened self-interest can keep oak woodland residents from importing GSOB-infested firewood,” Scott said. “This is a situation where the university can play a critical role in changing behavior through research and education rather than regulation.”

***

Tips for buying oak firewood

• Ask where the firewood comes from. If the source is San Diego County, ask what precautions the seller has taken about the goldspotted oak borer.

• Wood should preferably be bark-free, or it not, have been dried and cured for one year prior to movement.

• If you see D-shaped exit holes, be reluctant to buy unless you know the wood has dried for a year or longer.

For images or to read the UC Riverside press release, go to http://newsroom.ucr.edu/2715.