- Author: Pamela Kan-Rice

Innovation is key to keeping California farmers globally competitive. On Friday, May 5, the California Department of Food and Agriculture, California Farm Bureau Federation, California Association of Resource Conservation Districts, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, UC Davis and UC Agriculture and Natural Resources will forge a formal agreement to better connect the state's farmers with each other and with science-based information sources to assure the sustainability of the state's agricultural systems. Representatives of the six organizations will sign a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to form the California Farm Demonstration Network.

The scarcity of water, fossil fuel use, carbon emissions, groundwater quality, labor cost and availability, air quality and loss of soil fertility are some of the challenges to the long-term viability of farming in California. Soils and their sustained health play a major role in keeping California's agriculture viable for future generations.

“What we are striving to accomplish with the California Farm Demonstration Network is to create a means for farmers to learn, to discover and to innovate,” said Jeff Mitchell, UC Cooperative Extension cropping systems specialist, who is leading the effort with technical and funding assistance from MOU partners.

WHO:

- Karen Ross, secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture

- Paul Wenger, president of the California Farm Bureau Federation

- Ron Tjeerdema, associate dean of UC Davis College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

- Glenda Humiston, University of California vice president for Agriculture and Natural Resources

- Karen Buhr, executive director of California Association of Resource Conservation Districts

- Carlos Suarez, state conservationist for USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

WHEN: Friday, May 5

12:30 p.m. to 1 p.m. – Demonstration of differences in soil function resulting from management practices.

1 p.m. to 2 p.m. – Network partners describe their respective roles.

WHERE: Dixon Ridge Farms, 5430 Putah Creek Road, Winters, CA

VISUALS: A rainfall simulator will spray water over trays of different soils to show how on-farm management practices help the soil hold together.

Network partners will sign the memorandum of understanding.

BACKGROUND:

The statewide farm demonstration network builds upon and connects efforts across California including one created in Glenn County last year.

In Glenn County, the farmer-driven effort has provided the opportunity for local farmers to share innovative practices and hold honest discussions about opportunities and challenges related to these systems.

“The collaborative effort of the partners presents the opportunity to leverage resources based on local needs and increases the likelihood that innovative agricultural practices will be adopted sooner than they might have been without the networking opportunity,” said Betsy Karle, UC Cooperative Extension director in Glenn County.

With the California Farm Demonstration Network, the organizers hope to create more opportunities to connect local people, showcase existing farmer innovation, engage in new local demonstration evaluations of improved performance practices and systems, evaluate the demonstration practices, and share information with partners. They also hope to expand and connect other local farm-demonstration hubs throughout the state via educational events, video narratives and a web-based information portal.

- Author: Jeannette E. Warnert

Farmers and other members of the public are invited to the free event to see the system in operation and learn how overhead irrigation can be combined with no-till or minimum-till farming methods to create a more sustainable, profitable and environmentally sound agriculture industry. The field day includes a free barbecue dinner. To register, go to: http://ucanr.edu/TwilightRegistration.

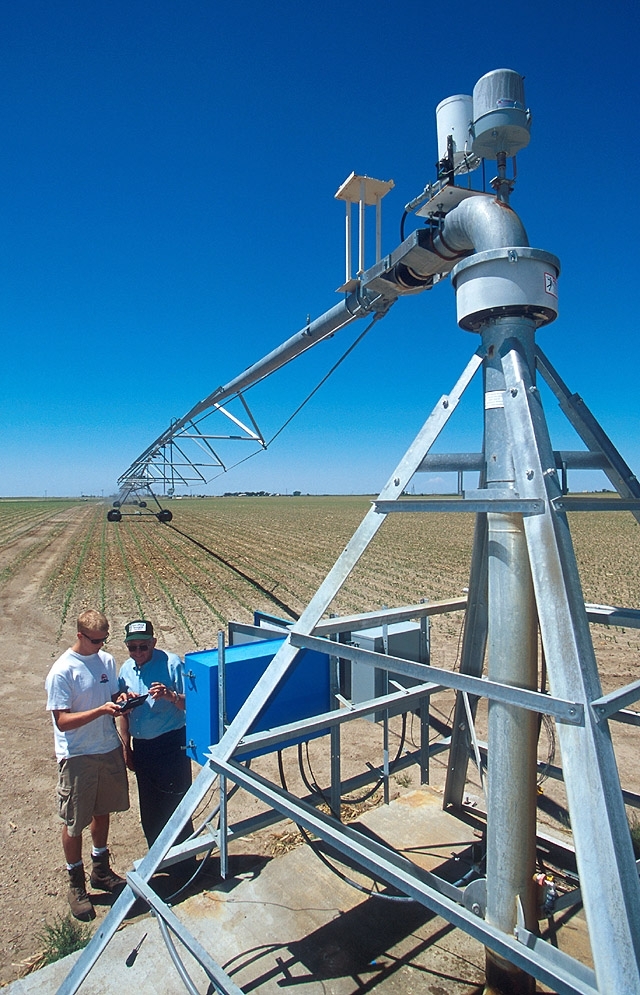

Overhead irrigation systems, such as center pivot systems, are the most prevalent form of irrigation nationwide; however, they have not been widely adopted in California to date. Recent technological advances in overhead irrigation – which allows integration of irrigation with global positioning systems (GPS) and management of vast acreage from a computer or smart phone – have boosted farmers’ interest in converting from gravity-fed surface irrigation systems, which are still used on 5 million acres of California farmland.

“We see tremendous possibilities for overhead irrigation in cotton, alfalfa, corn, onions and wheat production,” said Jeff Mitchell, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Plant Sciences at UC Davis. “There is also great potential for overhead irrigation in California’s $5 billion dairy industry for more efficiently producing feed crops like alfalfa, corn and sorghum.”

The use of the new system at the West Side Research and Extension Center, valued at about $100,000, was donated by Reinke Manufacturing of Hastings, Neb. Reinke will also sponsor the installation of its OnTrac irrigation monitoring system, which will give farmers and the public a real-time, online window of observation on crops growing and being irrigated by the new center pivot.

To begin with, the center pivot will irrigate an 8-acre half-circle of alfalfa and an 8-acre half-circle of cotton. All aspects of production – including irrigation system performance, weed control, fertilization, soil salinity and economic viability – will be monitored by a diverse team of researchers from UC Cooperative Extension, Fresno State University and UC Davis, plus farmer cooperators and industry members.

“In cotton and alfalfa, we will study deficit irrigation,” Mitchell said. “By controlling the speed of the pivot, pie-shaped segments will get either full irrigation, three-quarters of the full amount or about half of the full irrigation quantity.”

At the Sept. 13 field day, researchers will share what they have already learned about using center pivot systems in California. Participants will hear how overhead irrigation systems operate, how they are optimally managed, how soil water sensors can be used in conjunction with overhead systems and how overhead systems can result in higher application efficiencies and uniformities.

For more information, contact Jeff Mitchell, jpmitchell@ucdavis.edu, (559) 303-9689.

- Author: Jeannette E. Warnert

- Contact: Jeffrey P Mitchell

The UC Conservation Agriculture Systems Initiative challenges Californians to look 100 years, or even 500 years, into the future and imagine how today’s common agricultural practices will have impacted the environment and society.

The United Nations estimates world population in 2300 will be about 9 billion. There is likely to be significant development in the ensuing 300 years that reduces the amount of land for farming.

“We have to be able to do more with less,” said Jeff Mitchell, UC Cooperative Extension cropping systems specialist, echoing a common theme repeated by speakers at the launch of the UC Conservation Agriculture Systems Initiative (CASI) Jan. 27. “The global demand for food will be immense.”

Mitchell, other researchers and many innovative farmers have documented in more than 14 years of field research that changes in traditional farming practices – employing such technologies as precision irrigation, integrated pest management and conservation tillage – cut costs $75 to $150 per acre, reduce dust and diesel fuel emissions 60 to 80 percent, and prevent evaporation of about 4 inches of water per season from the soil surface.

This sort of objective data, plus favorable economic analyses and access to high-technology conservation equipment, are important factors in motivating farmers to change their practices, but they are not the only factors, Mitchell said. The Institute is committed to not only demonstrating and communicating the documented benefits of conservation agriculture but also identifying the drivers behind behavior change. The goal is converting 50 percent of California crop acreage to conservation practices by 2028.

“The cornerstone of sustainability is behavior change,” said Ron Harben of the California Association of Resource Conservation Districts, one of the Initiative’s founders. “Simply providing information has little or no effect on what people do.”

In parts of the U.S. and the world, conservation agriculture is common practice. World leaders in conservation agriculture include Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay, Western Australia and Canada. Within the next ten years, Mitchell reported, more than 85 percent of the cropland in the three South American countries is expected to be converted to conservation agriculture. Adoption rates are also quite high in parts of South Dakota, Nebraska, the Pacific Northwest, and areas throughout Alabama and Georgia. Yet implementation in California is still low.

In 2010, conservation tillage systems accounted for about 14 percent of the acreage in silage and grain corn, small grains for hay, silage and grain, tomatoes, cotton, dry beans, and melons in the nine-county Central Valley region. This was an increase from about 10 percent in 2008. Minimum tillage practices were used on about 33 percent of crop acreage in 2010, up from about 21 percent in 2008.

Mitchell said the implementation trends around the world, in the U.S. and in California “lend a certain inevitability” to its wide adoption in the San Joaquin Valley.

“This is not just about making a profit and optimizing yields,” Mitchell said. “By minimizing soil disturbance, preserving surface residue and including a greater diversity of crops in the rotation we are improving the soil resources and deepening the soil in an improved condition.”

The keynote speaker at the CASI launch was Hanford dairy farmer Dino Giacomazzi, a long-time innovator in conservation agriculture. Giacomazzi discovered conservation agriculture not long after taking over day-to-day operations of the Giacomazzi dairy from his father.

“It’s less work for more money,” Giacomazzi said. “Why aren’t people doing it? What’s the holdup?”

Perhaps in answer to his own question, Giacomazzi shared the reaction of his father to the new system being used on their farm. In their last conversation, the elder Giacomazzi lamented that, “Everything I’ve ever done, you’ve undone,” his son related at the meeting.

Dino Giacomazzi said many farmers’ tendency to be “enthralled” with tradition, their fierce independence, aversion to risk and fear of derision from neighbors contribute to their resistance to change. But accepting change is what is needed to adapt to a rapidly changing world.

Giacomazzi said the new Institute will play an important role in supporting farmers as they convert to conservation practices.

“This can’t be just a launch,” Giacomazzi said. “We must make this happen. Stay in touch.”

A video of the complete CASI January 27 launch meeting will soon be available at the Institute’s website http://ucanr.org/CASI.

- Posted By: Jeannette E. Warnert

- Written by: Jeannette Warnert, (559) 646-6074, jewarnert@ucdavis.edu

“The bar has been set,” said UC Cooperative Extension vegetable crops specialist Jeff Mitchell. “After toiling for more than a decade, we’ve finally succeeded in putting the pieces together this past season.”

Researchers harvested 3.4 bales per acre of cotton and 53 tons per acre of processing tomatoes using no-till techniques. Plots managed with conventional tillage practices averaged about 3.4 bales per acre for cotton and 49 tons per acre for tomatoes.

The research was conducted at the UC West Side Research and Extension Center near Five Points, Calif. Scientists established the cotton crop by direct seeding into beds that had not been touched since the preceding tomato crop, except by two herbicide sprays. The 2011 tomato crop was established with a no-till transplanter following the 2010 cotton crop, which had only been shredded and root-pulled under a waiver granted by CDFA’s Pink Bollworm Eradication Program.

The 2011 regime represented the first time since the start of the study in 1999 that the Five Points research team strictly followed no-tillage techniques for both crops. In past years, in which tomato yields reached the mid-60 tons per acre, in-season cultivation for weed control was used. In 2011, however, the goal of going completely no-till was realized in preparation for 2012, when the field will be converted to subsurface drip irrigation for all subsequent no-till plantings. Scientists believe the 2011 tomato harvest for both conventional and no-till plots was lower than in previous years because planting took place April 7 due to weather and scheduling delays.

UC Cooperative Extension agricultural economist Karen Klonsky estimates that switching to no-till production reduced expenditures by about $135 per acre for the tomato crop and about $40 per acre for cotton.

Future goals for conservation tillage production systems include profitability, resource quality, conservation, as well as broader ecosystem services.

“No-till makes sense as a means for lowering production costs and cutting dust and greenhouse gas emissions,” Mitchell said. “No-till also improves soil functions, such as increased carbon storage, greater stability of soil aggregates, increased porosity and water infiltration, and a larger population of earthworms.”

The benefits of no-till farming have been recognized by researchers and farmers in other regions, such as the Great Plains and the Pacific Northwest regions of the U.S., across much of Canada, and also throughout large areas of South America.

“These benefits start to pile up pretty fast once longer-term and broader sustainability goals are factored in,” Mitchell said.

Mitchell and his Five Points team are part of California’s Conservation Agriculture Systems Institute (CASI), a diverse group of more than 1,500 farmers, industry representatives, university, Natural Resource Conservation Service and other public agency members. Over the past 10 years, the team has come together to develop information on the true costs and benefits of the production system and irrigation management alternatives and to help develop appropriate sustainability goals for the long haul. For more information on the body of CT research, see the UC Conservation Tillage website.

“One of the things that CASI does is track changes in tillage management practices that are used throughout the San Joaquin Valley,” said long-time member and former air quality coordinator for the California Association of Resource Conservation Districts Ron Harben. “Our most recent survey for 2010 showed an increase of about 5 percent in no-till and strip-till acreage over previous years. As of 2010, over 47 percent of the cropland in the San Joaquin Valley is using some form of conservation tillage.”