- Posted By: Jaime Adler

- Written by: Greg Giusti, UCCE Forest Advisor

Understanding the Role of History on California’s Oak Forests

In his book The Destruction of California, Ray Dassmann (1965) chronicled the dramatic impact land-use practices have had on wildlife populations throughout California during the past 150 years. He articulates the impacts from the loss of wetlands, forest conversion and urban expansion on a number of economically important wildlife species. In his book, he quotes an early California pioneer, A. B. Clark (1852) who recorded the abundance of vertebrate diversity that was so apparent in the early days of exploration. Mr. Clark wrote, “ I have no where seen game as plenty as in the (central) valley. We killed an antelope in the morning. We could frequently see herds of deer and elk in different directions around us, as well as wild horses”. Today, concentrations of deer, elk and waterfowl populations can be found in remnant habitats distributed in small, isolated patches throughout the valley.

More recently, Walter (1998) provides a complete overview of how past land-use practices have changed the landscape of California so dramatically that in some cases counties “have lost their natural heritage” and are mere remnants of their past biological richness. Brown et. al. (1994) and Marchetti and Moyle (1995) have outlined the once abundant numbers of salmon and how historical land-use practices directly impacted anadromous fisheries and how the legacy of these practices continues to impact these species. They specifically identify water diversions and related watershed degradation caused by past and on-going human activities as the direct cause of these declines. Moyle et. al. (1994) has identified as many as 10 anadromous species (including salmon, steelhead trout, lamprey, sturgeon, smelt) that meet the scientific criteria necessary for special protective status.

The common thread binding the terrestrial and aquatic inhabitants of pre-settlement California is the fact that many of these species were found in areas that we commonly referred to as oak (Quercus) woodlands. In many cases, the abundance that has been chronicled illustrates the importance of oak habitats to many of the species which spent a significant portion of their life history living in, or migrating through, oak woodlands. Because of their ubiquitous distribution oaks have been impacted throughout California during the past century. An early account written by Willis Linn Jepson (1909) states; “In some regions where the horticultural development has been rapid or the needs of an increasing population urgent, extensive areas have been cleared to make room for orchards or gardens, and scarcely a [valley oak] tree remains to tell the story of the old time monarchs of the soil, in other regions the destruction has not been so complete” (Pavlik et. al. 1991). Modern day land-use impacts on oak woodlands continue through urbanization and the conversion of oak woodlands to intensive agriculture.

California’s History of Forest Policy toward Oaks

In 1885, the Governor of California approved an act that authorized the appointment of a three-man State Board of Forestry, the first such body in the nation. Because of a lack of clear statutory authority and minimal budgeting, the original Board was only able to act in an educational and advisory capacity. By 1905, the Board of Forestry was supplemented by creation of the post of State Forester and in 1927 the Division of Forestry was organized.

In 1947, the original Forest Practice Act was passed by the State Legislature. Although the responsibilities and powers of the Board under the old act were less than they are today, the 1947 Act laid important foundations of experience and procedure which led to further development for the Board.

Throughout the period of the 1950s and 1960s, the Board of Forestry functioned under the mandate of the 1947 Act by formulating forest policy for the state. When the Division of Forestry was elevated to departmental status in 1977, the organizational relationship between the Department and the Board was retained. This reorganization of the Department had no effect upon the Board's mandated duties and responsibilities. With the passage of the Z'berg-Nejedly Forestry Practice Act of 1973, the Legislature reorganized the Board and concomitantly expanded its powers and responsibilities. To achieve a balanced approach to forest land policy, the Public Resources Code delineates the character of the Board by designating that five members will be from the general public, three are chosen from the forest products industry, and one member is from the range-livestock industry.

The Board is recognized as having the legislative authority to regulate both privately owned conifer and oak woodland forest types. Historically, the Board has focused its regulatory authority on those lands capable of producing commercial lumber products choosing to support an educationally based program for oak woodlands. The educational path was established with the creation of the University of California’s Integrated Hardwood Management Program (IHRMP) in the mid-1980s. In 1993 the Board delegated to the IHRMP the responsibility of assisting counties in the development of locally based conservation strategies for oak woodlands. In response to this directive, counties have developed a wide array of resolutions, ordinances and monitoring efforts through a variety of committees, Board of Supervisor actions and local initiatives.

Current Forest Policy and Oaks

Under the direction of the Z'berg-Nejedly Forestry Practice Act of 1973 the Legislature identified the timberlands of the State to be “among the most valuable of natural resources….are of great concern ….relating to their utilization, restoration and protection”. The legislature further recognized the need to “encourage prudent and responsible forest resource management while giving consideration to the public’s need for watershed protection, fisheries and wildlife, and recreational opportunities…”. The Act further defined timberlands as, “[non-federal] lands available for, and capable of, growing a crop of trees of any commercial species…..”. The Board further defined “commercial species” to include most economically important conifers and some hardwood species, when growing on timberland.

The impact of the Z'berg-Nejedly Act has continually evolved, since its inception. The Act, through a separate set of Forest Practice Rules, recognizes the need for the protection of watershed elements by establishing minimum standards for streams zone protective widths (by stream class), archaeological sites, soil stability and cumulative effects. These requirements are mandatory for any landowner who wishes to engage in timber harvesting. The Act in combination with the Rules is designed to identify and mitigate any potential negative impacts from the harvesting of timber as a requirement of the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). As a result of the Act, a landowner is required to secure the services of a Registered Professional Forester (RPF) to submit a Timber Harvest Plan (THP) for review and approval by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CDF) prior to the harvesting of commercial tree species. The THP, only one of several vehicles used by CDF and RPFs, is viewed by the State as serving as the functional equivalent of an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) under CEQA..

By definition, most species of Quercus are currently not recognized as commercial species. Only under specific circumstances are pre-determined oak species (Q. Kelloggi and Q. Garryana) recognized by the Forest Practice Rules. In all other situations, if any oak species, including the two identified, occur on lands not designated as timberlands they are not afforded protection under the Forest Practice Act, thereby, not given statewide considerations under CEQA. However, many of these oak woodland species occur as a continuum of forest canopy in many watersheds of California. In many situations throughout the State a common vegetative pattern exists with conifer dominated coastal and mountainous forests transforming into oak dominated types in drier or lower elevation sites.

Inconsistency is in the Policy not the Forests

An obvious inherent conflict with current land-use forest policy is the recognition of tree species (and thereby habitats) afforded protections under CEQA relative to their economic values and not their ecological values thereby creating an artificial delineation of forest types. A glaring example of the inherent inconsistency with this current policy situation is best exemplified by the State’s role in providing protection to salmonid species in northwestern California under CEQA. Under the current Forest Practice Rules, salmon and steelhead, are afforded some level of protection (though a recent independent scientific panel determined the level of protection was inadequate to protect salmonid resources: Ligon et. al. 1999) when they enter freshwater habitat located in a conifer forest setting. However, in many cases, those same fish will continue their upstream migration passing through the conifer belt and ultimately complete their journey in a predominately, oak woodland habitat type. This scenario is true for fish in the Russian, Navarro, Eel, Klamath, Smith and Sacramento and San Joaquin River systems. Under these scenarios, the stream and the forest cover represent an ecological continuum for the fish as it moves through the system from the marine environment to its natal spawning grounds in order to complete its life history. Furthermore, once spawned and hatched, many of the juvenile fish will spend a significant portion of their early life stages in the oak dominated portions of the watershed. However, as the fish move from one forest type to another, the level of protection is not contiguous thereby providing only a minimal level of protection for a small portion of the overall habitat.

This inconsistent application of standardized protective measures is most apparent in those counties with the absence of local requirements to mitigate land-use impacts on streams i.e. grading ordinance, stream zone buffers, etc. Under the existing statewide forest management policies the current statewide mechanism to protect forest streams (Forest Practice Rules) do not provide a continuous level of protection throughout a watershed based on the definition of commercial vs. non-commercial tree species.

The lack of a standardize statewide approach to oak conservation has promoted a variety of measures to be developed, modified and implemented throughout the oak region of California in an attempt to address both riparian and upland issues. A collection of resolutions (Tehema, Shasta, Madera Counties), ordinances (Sonoma, Napa, Santa Barbara), evaluation committees (Lake, Madera), monitoring efforts (El Dorado) and ballot measures (Santa Barbara) targeting an equally wide array of issues. In many instances, the adopted mechanisms have focused on a single resource issue such as water quality (Napa and Sonoma Counties) or heritage tree preservation (various county tree ordinances) and have not produced comprehensive measures with adequate monitoring mechanisms capable of evaluating their effectiveness or large landscapes or watersheds.

The current inconsistencies in oak management policies and strategies will certainly continue to fuel the intense debates currently underway throughout the oak region of California as land-use practices increase in scope and magnitude. A need exists to evaluate current local policies and develop comprehensive strategies that promote, protect and enhance oak woodlands and all of their inherent resources.

Literature Cited

Brown, L. R., P. B. Moyle and R. M. Yoshiyama. 1994. Historical Decline and Current Status of Coho Salmon in California. No. Am. J. of Fisheries Mngt. 14: 237-261.

Dassman, R. F. 1965. The Destruction of California. MacMillan Co. New York. 247pp.

Marchetti, M. P. and P. B. Moyle. The decline of sea-run fishes in California: An ongoing tragedy. Cal Ag. 49 (6): 74.

Moyle. P. B. 1994. The Decline of Anadromous Fishes in California. Consv. Biol. 8 (3) 869-867.

Walter, H.S. 1998. Land Use Conflicts in California. Eco. Studies 136:108-125.

- Posted By: Jaime Adler

- Written by: Douglas McCreary and Jeannette Warnert

Many blue oak trees in California foothills might be more accurately described as “silver oaks” this year. From a distance, they shimmer with a silvery halo. On closer inspection the outermost leaves are coated with a white to gray powdery fuzz.

The cause, according to Doug McCreary of the Integrated Hardwood Range Management Program at UC Berkeley, is powdery mildew. Powdery mildew, a group of fungi that causes a white, flour-like growth on the surface of leaves, is common on roses, begonias, grapes and many other ornamental plants and agricultural crops.

“People have called us worried that the affected trees may be showing signs of SOD, but this is clearly not the cause. SOD symptoms are far different, blue oak is not a SOD host and SOD is restricted to coastal forests,” McCreary said.

McCreary assures oak lovers that powdery mildew rarely kills the majestic trees. Even small seedlings that have all of their leaves severely infected usually survive and recover.

“Powdery mildew makes it more difficult for the affected leaves to photosynthesize and produce food, and if it’s severe enough, it can also result in the leaves distorting, curling up, dying and falling to the ground,” McCreary said. “But most affected trees will simply grow a new crop of leaves later in the summer or the following spring. And if weather conditions return to a more normal pattern next year, with little or no rainfall after March, it is unlikely that powdery mildew would continue to be severe or widespread.”

Some people may be inclined to treat affected trees with fungicides. However, these treatments are most effective when the symptoms first appear, which occurred weeks or months ago. It is also generally not recommended to treat trees in wildland settings. There are too many trees to treat and the potential environmental risks of applying fungicides across a large landscape can outweigh the benefits. Above all, McCreary said, don’t panic and cut down the trees, even if all their leaves fall off.

“The trees are still very much alive,” McCreary said. “Losing their foliage is just the oak’s way of dealing with an unwanted pest. By this time next year they should again be leafed out without that silver covering currently observable.”

The unusually wet March and April is at least partially responsible for the higher-than-normal incidence of powdery mildew in blue oaks, he said. Increased incidence of powdery mildew has also been reported on California black oaks and coast live oaks on the coast.

“Powdery mildew doesn’t need rainfall, but it is favored by warm conditions, high humidity and low light and it loves young, succulent foliage,” McCreary said. “Because California was blessed with above average rainfall this past spring, there has been – and continues to be – considerably more moisture in the soil. Under these conditions, oak trees will grow a ‘second flush’ of leaves, usually in May or early June, that is very susceptible to powdery mildew.”

- Author: Jaime Adler

To Register Click Here by June 24th!

When: Thursday, June 30, 2011 9:00am-2:30pm. Please register by Friday, June 24th.

Where: Avenales Ranch Road, Pozo, CA 93453, San Luis Obispo County . We will meet at the American Canyon Forest Service Campground

Who: Anyone interested in research, education, management and conservation of oak woodland ecosystems. This includes landowners and managers, consulting range managers and registered professional foresters, community and conservation groups, land trusts and policy makers.

What: Agenda for the day

9:00 am - Arrive for coffee and registration

10:00 am - Brief Introduction to Avenales Ranch

10:15 am - Oak woodland management concerns

10:30 am - Oak regeneration, seeding, stump-sprouting

11:15 am - Oak thinning, measuring, management

12:00 pm - Lunch*

12:45 pm - Forest production and management

1:15 pm - Wildlife in Oak woodlands

1:45 pm -Sycamore regeneration study

2:15 pm - Alternative Review Program

2:30 pm - Adjourn

*Please remember to bring your own bag lunch.

In addition, appropriate clothing and footwear are recommended. There will be some off-trail hiking.

Please register by June 24th by Clicking Here!

For more detailed information, including directions, please Click Here! Please note: you do not need to be an Oak Webinar participant to attend this field trip.

Questions? Email Rick Standiford: standifo@berkeley.edu

Pictures from one of our field trips to the Sierra Foothills Research and Extension Center:

- Posted By: Jaime Adler

- Written by: Bill Tietje and Royce Larsen, UC Cooperative Extension

California residents who want to plant an oak tree or two on their property, often find it challenging, given our climate with irregular winter rains and no summer rainfall, to keep the newly-planted trees green and growing. A devise that has come onto the market recently is dubbed the “Groasis Waterboxx”. According to the website (Groasis.com) the Waterboxx has proven effective at “self-watering” new plantings, even in a truly desert climate.

Recently, we started a trial to test the Waterboxx by planting some oak seedlings and elderberry plants in a remote area. The Waterboxx is a round plastic “box” that fits around the tree trunk. The inward-slanting corrugated top cools during the night and channels condensed dew and heavy fog that collects on the top to the base of the tree. The Waterboxx also provides some protection for the newly planted tree and reduces the evaporation of water from the soil around the base of the tree, important additional benefits for new plantings. Once the tree is established, the Waterboxx can be removed and reused for another plant. Placing a collar around a tree that collects moisture and at the same time provides some protection can be a big incentive and a boost to getting that tree started.

As you can understand, the Waterboxx can be a big help as an alternative to carrying water to distant areas or setting up a drip system. For more information about the Waterboxx, contact your local UC Cooperative Extension Office or go to the Groasis Waterboxx website: Groasis.com. On the website you will notice that the inventor of the Waterboxx is providing users the opportunity to provide information on the growth and survival of their plantings. You may want to check it out.

- Posted By: Jaime Adler

- Written by: Adina Merenlender, CE Specialist

California’s hardwoods have so many virtues it is difficult to count them all. Only recently scientists have come to appreciate the influence that living hardwoods exert on stream channel shape as the key to providing good habitat for all aquatic species, including salmon in coastal California streams. It is well known that wood in streams provides habitat for a broad range of fresh water species and can influence the shape of the stream channel and important ecosystem processes, such as moving sediment and nutrient cycling. Wood also provides important habitat for fish by creating pools, providing shade and hiding places from predators, protection from high flows, food and shelter for invertebrates, woodjams that store spawning gravels and organic matter, and facilitates riparian plant regeneration. Wood is considered one of the most important habitat components for anadromous salmonids and with salmon on the decline it is important we ensure the presence of wood in California’s coastal streams.

Previously, scientists attributed all of these qualities to large pieces of dead wood from species that rot slowly such as the infamous California redwoods. But this begs the question: What is happening in streams lined by hardwoods such as California bay laurel, live oaks, alders, and willows commonly found in our mediterranean-climate woodlands? Field research conducted by Dr. Jeff Opperman, UC Berkeley alumnus now working for The Nature Conservancy, in 20 stream reaches in the northern parts of the San Francisco bay area, documents that living hardwoods are playing an essential role in California’s hardwood dominated streams by providing permanent structure that interacts with stream flow and gravel movement to create essential aquatic habitat for salmon and other native species (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Extracted from OPPERMAN, J. J. and A. M. MERENLENDER. 2007 Living trees provide stable large wood in streams. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 32:1229-1238 (a) A red willow (Salix laevigata) that has fallen into Wildcat Creek (Aladmeda County, CA) but remains rooted and living (photo taken looking upstream).The lower arrow indicates sprouts growing from the lower branch of the willow. The upper arrow indicates a branch that has reoriented to become the primary source of photosynthesis for the fallen tree. A channel-spanning wood jam has accumulated upstream of this willow, which has contributed to the formation of the pool in the lower left portion of the picture. (b) The shaded areas denote all the wood that is still living within this wood jam.

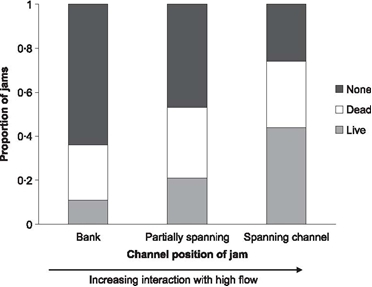

As you can imagine trees that fall or grow over the stream and remain rooted and alive are more stable over time and and can withstand sizeable storms. After falling into the stream, hardwoods can often sprout new branches or bend into new shapes that result in vertical branches to capture more light for photosynthesis. A live tree spanning a creek with leaves on vertical branches creates significant shade and captures additional wood and organic material all to the benefit of the fish living below (Figure 1). These persistent hardwoods provide important in-stream structure in streams with riparian corridors that lack large conifers. In fact, in the 20 streams Jeff studied living hardwoods were the key piece of wood within a wood jam, the primary mechanism by which wood in?uences channel morphology, and had greater influence on channel morphology than larger pieces of dead wood found. Only 74% of the wood jams without live wood persisted to allow for scowering and pool formation in the stream over 1-2 years while 98% with living wood as a key piece remained in place for longer. Wood jams that span the entire channel provide the greatest influence over stream morphology and create complex habitat that maintains cooler safer waters for fish. Out of all the channel-spanning jams measured by Jeff, 44% had a living hardwood as key piece (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Extracted from OPPERMAN, J. J. and A. M. MERENLENDER. 2007 Living trees provide stable large wood in streams. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 32:1229-1238 The proportion of all wood jams with a live key piece (shaded), dead key piece (white) or no key piece (black), based on channel position of the wood jam.

Clearly, California hardwoods are a necessary component within California’s fresh water aquatic ecosystems because they contribute to ?sh habitat by creating and maintaining wood jams, forming pools, and providing cover. Unfortunately, wood in streams is often removed by landowners, in some cases to protect property, but in other cases because of the desire for a clean stream or for easily accessible firewood. To stress the importance of maintaining wood in streams for fish habitat I, along with Jeff, and David Lewis a UCCE Watershed Management Advisor for Sonoma County, wrote a free publication for landowners titled “Maintaining wood in streams: A vital action for fish conservation.” Please click here to access the publication and learn more about this topic: http://ucanr.org/freepubs/docs/8157.pdf.