- Editor: Sophie Kolding

- Author: Jan Gonzales

The goldspotted oak borer (GSOB; Agrilus auroguttatus) continues to attack and contribute to the high mortality of tens of thousands of oaks in San Diego County and the threat to oaks throughout southern California remains a considerable concern. In effort to inform professionals who are responsible for the stewardship of oaks and oak woodlands, a series of workshops has been offered in six southern California counties in which oaks may be at risk: Ventura, Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, Orange and San Diego. The overlying objective was to spread the knowledge of goldspotted oak borer and minimize the spread of this non-native insect into new areas. These day-long events offered multi-agency presentations, hands-on displays, outreach materials and in some locations, short field trips.

Figure 1. Dead oak trees due to GSOB Figure 2. Two Adult GSOB on penny

(Photo source: Tom Coleman, USDA Forest Service) (Photo source: Tom Coleman, USDA Forest Service)

In cooperation, the USDA Forest Service, CAL FIRE, and the University of California have partnered with other local agencies, tribes and organizations to provide these workshops. Presenters at each session were coordinated from a cadre of specialists and researchers. Key speakers included Tom Coleman, Paul Zambino, Sheri Smith, Larry Swann, Lisa Fischer and Matthew Bokach (USDA Forest Service and Forest Health Protection); Tom Smith, Kim Camilli and Kathleen Edwards (CAL FIRE);Tom Scott, Doug McCreary, Jim Downer and Kevin Turner (University of California Cooperative Extension); and Vanessa Lopez (PhD candidate in the Entomology Department, UC Riverside). Introductory workshops were held monthly from September 2010 through February 2011. Topics covered were:

- GSOB history and distribution

- GSOB identification and biology

- Ecological and economic impacts of infested oaks and oaks at-risk

- Integrated best management practices for GSOB infested and at-risk oak woodlands

- How to prepare for potential outbreak

- Utilization of GSOB infested oak wood

- Restoring oak woodlands impacted by GSOB

Figure 3. Larvae Feeding Galleries, seen in cambium Figure 4. GSOB larvae in firewood (Photo source:

of oak wood cross-section (Photo source: Tom Scott, UC Cooperative Extension)

Kim Camilli, CAL FIRE)

In early May 2012, two additional workshops were held to provide updates from on-going research, best management practices and mitigation and education efforts. The session on May 1st was held in Altadena in partnership with the Los Angeles County Fire Department-Forestry Division and the County Parks and Recreation Department. The following workshop, held on May 2nd, was hosted in partnership with the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians in Temecula.

Information Highlights:

- The goldspotted oak borer in an introduced, non-native beetle attacking and killing coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), California black oak (Quercus kelloggii), and canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis) trees in San Diego County.

- The adult goldspotted oak borer (GSOB) Agrilus auroguttatus is a small, bullet-shaped beetle about 10mm (0.4 in.) long and has six golden yellow spots on its dark green forewings.

- Mature larvae are white, legless, slender and about 18mm (0.75 in.) long with two pincher-like spines at the tip of the abdomen. Larvae feed under the bark on the trunk and larger branches.

- Larval feeding kills patches and strips of cambium tissue beneath the bark, which causes dark staining and sap flow. The larvae pupate in the outer bark and leave D-shaped exit holes about 1/8 in. wide when they emerge.

- GSOB produce only one beetle generation per year.

- The goldspotted oak borer’s peak flight and breeding season is May through October.

- There is on-going research being conducted on biological and chemical GSOB control methods for preventative management; trees at various degrees of infestation; and the wood from infested, dead and felled trees.

- Currently, there are no effective treatments that can eradicate GSOB once it becomes established.

- Goldspotted oak borer larvae and pupae can survive under the bark of wood from large branches and trunks for up to a year after a tree dies.

- Currently, best management practices to minimize introduction of GSOB to new areas is to let wood cure at least two years after the tree dies before moving firewood from infested areas or grind wood into 3-inch particles.

- Before any type of treatment on oaks is initiated for GSOB infested trees or as a preventative measure on high-valued trees, a management plan should be developed first.

- There are no quarantines or zones of infestation in place by statewide authorities for GSOB; however, in 2011 the California Pest Council established the California Firewood Taskforce, a coalition of stakeholders that initiates and facilitates efforts within the state to protect our native and urban forests from invasive pests that can be moved on firewood.

- The Early Warning System is a citizen scientist program established to enlist the help of those concerned about oaks for the purpose of identifying oak tree health in southern California urban and woodland areas.

- Information and resources may be found on the Goldspotted Oak Borer website, www.gsob.org. To stay informed of current news, information and future training opportunities, we recommend you join the GSOB email list.

(Photo source: Lorin Lima, UC Cooperative Extension-San Diego)

Nearly 500 professionals attended these workshops. Findings from follow-up workshop surveys indicate that potentially more than 2,600 others will learn about GSOB through outreach extended by workshop participants. Although evaluation and survey responses point towards a successful series of GSOB workshops, the threat of further goldspotted oak borer attacks remains. As the peak emergence and flight season occurs during the same time of year of increased vacation travel and camping in southern California, we are all encouraged to share the news about GSOB and it’s threat to oaks with others along with the message to not move firewood – “Buy It Where You Burn It.”

For more information:

Goldspotted Oak Borer website: http://www.gsob.org

California Firewood Task Force: http://www.firewood.ca.gov

Goldspotted Oak Borer - The Center for Invasive Species Research, UC Riverside:

http://cisr.ucr.edu/goldspotted_oak_borer.html

Goldspotted Oak Borer – UC Statewide Integrated Pest Management: http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/NATURAL/index.html

- Author: Royce Larsen

- Editor: Sophie Kolding

Most of the oak woodlands in California are privately owned. The major use of Oak Woodlands is for grazing, primarily for beef cattle. The ranching industry plays an important role in maintaining a sustainable, culturally meaningful, and ecologically rich landscape (Huntsinger and Hopkinson, 1996) in our oak woodlands. Of the many challenges facing ranchers, droughts can be severe.

The great drought of 1862–1865 wreaked havoc on the state and the cattle industry (Burcham, 1957). Since that time we have had severe droughts about 8 times (George et. al. 2010). Even with less severe droughts, cattlemen have a stressful time dealing with changes in forage production. With less forage production, cattlemen either have to reduce herd size, move cattle to other states or locations, or provide extra feed at a great expense. If cattle are sold, it may take several years to build the herd back.

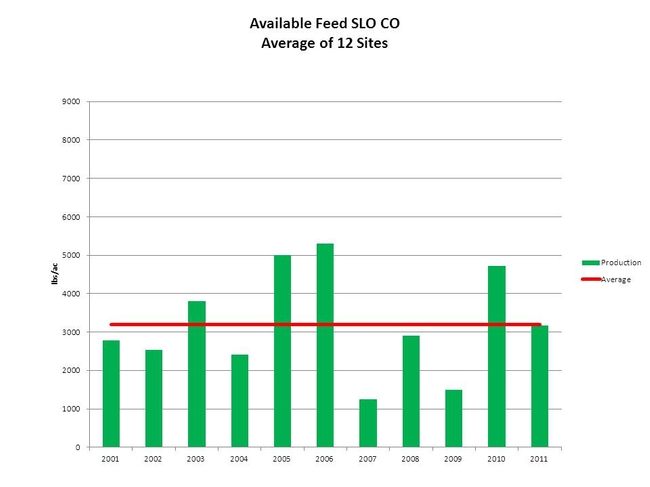

Not all droughts are equal. Droughts tend to be more common in the rain shadow along the Coast Range adjacent to the west edge of the San Joaquin Valley (George et. al. 2010). Even though drought conditions create havoc with management of ranches, ranchers also have to deal with wetter than normal years. There is no such thing as an average year, which makes management decisions very difficult. Forage production and quality can vary greatly from year to year, and is strongly influenced by the timing and amount of rainfall (George et. al. 2001). For example, forage production in San Luis Obispo County over the last 11 years has varied by as much as 4000 lbs/ac (Figure 1). Rainfall amount and timing played a significant role in this variation, which varied by 18 inches of annual precipitation.

Figure 1: Peak Forage Production in San Luis Obispo County from 2001 – 2011.

An average of 12 sites across the county.

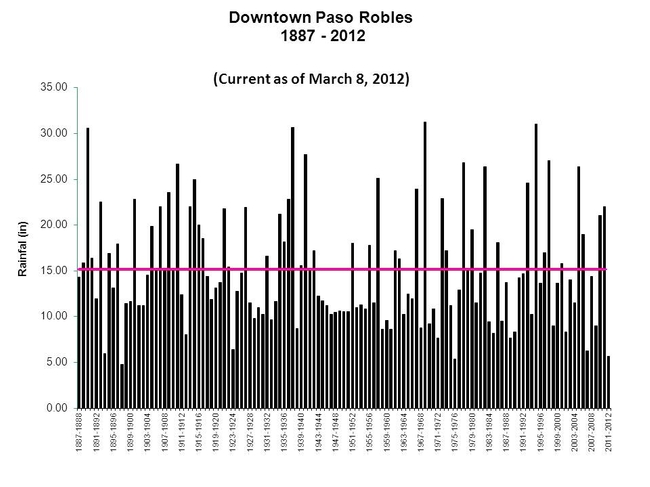

It is just a fact of life that rainfall amount and timing varies. For example, the lowest rainfall recorded in downtown Paso Robles was 4.8 inches in 1898 (Figure 2). The highest recorded was 31.3 inches in 1969, the year of the big flood. It is important to notice that 6 out 10 years are below average (Figure 2). This means that the four years that are above average are usually wet years, which often produces extra forage. For more practical purposes, the years that are below the average determine what and how much forage can be produced on a ranch, which determines the number of cattle that can be grazed on a sustainable basis. It is very important to the ecological health of the oak woodlands / grasslands to maintain proper stocking rates to achieve the desired grazing level. Maintaining the proper amount of residual dry matter (RDM) has become the standard to determine grazing use on oak woodlands and annual grasslands. Properly managed RDM provides protection from soil erosion and nutrient losses, and also plays an important role determining the following year’s production and composition of species (Bartolome et. al. 2006). To accomplish this requires constant change in management by ranchers. I applaud those ranchers who work so hard to accomplish this.

Figure 2: Rainfall records at the down town Paso Robles. Data is based on water

year July 1 – June 30. Average precipitation is 15 in/yr.

Below are images taken of the peak forage production for San Luis Obispo County:

Spring 2006 normal, wet conditions

Soda Lake Site Cambria Site

Spring 2007 drought conditions

Soda Lake Site Cambria Site

References

Burcham, L.T. 1957. California range land: An historico-ecological study of the range resource of California. Division of Forestry, Department of Natural Resources, State of California, Sacramento, California, USA.

Bartolome, J.W., W.E. Frost, N.K. McDougald, and M. Connor. 2006. California guidelines for residual dry matter (RDM) management on the coastal and foothill annual rangelands. Oakland, CA USA: Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California, Publication 8092.

Huntsinger, L. and P. Hopkinson. 1996. Viewpoint: Sustaining rangeland landscapes: a social and ecological process. Journal of Range Management 49(2):167-173.

George, M.R., R.E. Larsen, N.M. McDougald, C.E. Vaughn, D.K. Flavell, D.M. Dudley, W.E. Frost, K.D. Striby, and L.C. Forero. 2010. Determining Drought on California’s Mediterranean-Type Rangelands: The Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program. Rangelands 32(3):16-20.

- Posted By: Sophie Kolding

- Written by: Tom Scott

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – A catastrophic infestation of the goldspotted oak borer, which has killed more than 80,000 oak trees in San Diego County in the last decade, might be contained by controlling the movement of oak firewood from that region, according to researchers at the University of California, Riverside.

“This may be the biggest oak mortality event since the Pleistocene (12,000 years ago),” said Tom Scott, a natural resource specialist. “If we can keep firewood from moving out of the region, we may be able to stop one of the biggest invasive pests to reach California in a long time.”

A cadre of UC researchers is leading the effort to assess and control the unprecedented infestation, in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service. Scott and others are working to identify where the infestation began, how it is spreading through southern California’s oak woodlands, and what trees might be resistant. In October 2010 Scott and other UCR researchers received $635,000 of a $1.5 million grant of federal stimulus money awarded to study the goldspotted oak borer and sudden oak death.

The goldspotted oak borer (Agrilus auroguttatus), which is native to Arizona but not California, likely traveled across the desert in a load of infested firewood, possibly as early as the mid-1990s, Scott said. Researchers have confirmed the presence of the beetle as early as 2000 near the towns of Descanso and Guatay, where nearly every oak tree is infested.

The half-inch-long beetle attacks mature coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), California black oaks (Quercus kelloggii) and canyon live oaks (Quercus chrysolepis). Female beetles lay eggs in cracks and crevices of oak bark, and the larvae burrow into the cambium of the tree to feed, irreparably damaging the water- and food-conducting tissues and ultimately killing the tree. Adult beetles bore out through the bark, leaving a D-shaped hole when they exit.

Scott and Kevin Turner, goldspotted oak borer coordinator for UC Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) at UCR, said that field studies in San Diego County in the last six months point strongly to the transportation of infested oak firewood as the source of the invasion that threatens 10 million acres of red oak woodlands in California.

Outbreaks have been found 20 miles from the infestation area, implicating firewood as the most likely reason for the beetle infestation leap-frogging miles of healthy oak woodlands to end up in places like La Jolla. In contrast, communities that harvest their own trees for firewood have remained relatively beetle-free, even as adjacent areas suffer unprecedented rates of oak mortality. Both examples support the growing conviction that the movement of infested firewood is the primary means by which the beetles are spreading, Scott said.

California’s coast live oaks, black oaks and canyon live oaks seem to have no resistance to the goldspotted oak borer and, so far, no natural enemies of the beetle have been found in the state.

The devastation can be measured in costs to communities and property owners for tree removal, the loss of recreation areas and wildlife habitat, lower property values and greater risk of wildfires. The three oaks under attack may be the single most important trees used by wildlife for food and cover in California forests and rangelands.

Most of the dead and dying trees are massive, with trunks 5 and 6 feet in diameter, and are 150 to 250 years old. The cost of removing one infested tree next to a home or in a campground can range from $700 to $10,000. The cost of removing dead and dying trees in San Diego County alone could run into the tens of millions of dollars. In Ohio, which has experienced similar losses from the emerald ash borer, several small cities went bankrupt because of tree removal costs associated with that beetle, Scott said.

So many oaks have died in the Burnt Rancheria campground on the Cleveland National Forest – a favorite spot for campers who favored the shade of a dense canopy of coast live oaks – that the Forest Service has had to erect shade structures. Other state and county parks in the region have suffered equally devastating losses.

Turner said an Early Warning System of community volunteers launched in San Diego County now includes representatives from every southern California county as far north as Ventura. Those volunteers are trained to monitor the health of oak trees in their communities and report any unusual changes.

At the same time, a network of UC Cooperative Extension, ANR, U.S. Forest Service and other agencies in the region is working with woodcutters, arborists and consumers to discourage the sale and transportation of infested wood. Wood that is bark-free or that has dried and cured for at least one year is generally safe to transport, Scott said. This relatively small change in firewood-handling methods could save a statewide resource without jeopardizing the firewood industry, he said.

Local, state and federal agencies recognize that firewood production is one of the least-regulated industries in California, and view UC Cooperative Extension education as the best means of stopping goldspotted oak borer movement in firewood.

“Quarantines don’t work, but enlightened self-interest can keep oak woodland residents from importing GSOB-infested firewood,” Scott said. “This is a situation where the university can play a critical role in changing behavior through research and education rather than regulation.”

A cross-section of an oak infested by the goldspotted oak borer shows the damage done by the non-native beetle.

To view original article, Click Here.

Related Links:

Goldspotted Oak Borer Information

GSOB Research at UCR

UC Cooperative Extension

- Posted By: Jaime Adler

- Written by: Michael Hamilton, Director of the Blue Oak Ranch Reserve and Rulon Clark, Assistant Professor at CSU San Diego

One would think that in the oak woodlands, the most important predators would be mammals such as mountain lion, coyote and bobcat. But new field research is discovering that the most important predator may be rattlesnakes in terms of overall biomass. Rulon Clark, an assistant professor at California State University at San Diego, and his team of eight graduate and undergraduate students, are studying rattlesnakes and their prey at one of the newest University of California Natural Reserves, Blue Oak Ranch Reserve. The 3,300 acre reserve is situated on the west slope of Mount Hamilton, only 10 miles from San Jose.

Clark and his students have documented densities of rattlesnakes on the reserve that far exceed any they have previously encountered throughout California, including the remote Mojave Desert. Rattlesnakes have likely been left alone by humans at Blue Oak Ranch Reserve for many decades. Given the local abundance of wild prey, the snakes have reached population levels that may have been typical prior to centuries of persecution by ranchers and hunters, according to Clark.

The rattlesnake researchers, dubbed “Team Crotalus,” have just completed nearly two months of detailed studies of the interactions between the northern Pacific rattlesnake, Crotalus oreganus, and its preferred prey species the California ground squirrel, Spermophilus beecheyi. When confronted by predators, many animals engage in lengthy, conspicuous interactions involving stereotyped signals and displays. These antipredator signals have been studied mainly as warning signals directed toward conspecifics, even though they may also serve to communicate with predators. Studies of how these signals affect predators have been rare because predation is infrequent and difficult to observe in the field.

Team Crotalus has begun assembling a one-of-a-kind database of natural antipredator signaling interactions and predator responses. To do so, they are using a high tech assortment of tools. These range from radio telemetry transmitters surgically implanted in the rattlesnakes, to miniature, battery-powered webcams. The webcams transmit live video of snake/squirrel interactions several miles away to the reserve headquarters for recording and observation. The team also confronts snakes with a mechanical, taxidermied rodent affectionately named “Robosquirrel.” The Robosquirrel is programmed to make antipredator sounds and movements to snakes in experimental encounters. The bouts allow the scientists to test predictions of how predators and prey communicate in controlled experiments. (Watch a video of a robosquirrel being struck by a rattlesnake).

Team Crotalus research has focused on the behavior of rattlesnakes confronted by two prey species, ground squirrels and kangaroo rats. These two distantly related rodents have evolved sophisticated anti-snake behavior independently. Comparing the two rodents’ interactions will allow the scientists to examine the role of various ecological and organismic factors that shape predator-prey signaling interactions. Their unique approach combines these methods in studies that simultaneously consider both prey signaling behavior and predator responses in an experimental context. This system promises to provide novel insights into such areas as honesty in animal communication, antagonistic coevolution, and the role of animal sensory systems in shaping signaling behavior.

For more information:

Bree Putman’s Blog: Strike, Rattle and Roll http://strikerattleroll.blogspot.com/

Rulon Clark Lab http://www.bio.sdsu.edu/pub/clark/Site/Home.html

Blue Oak Ranch Reserve http://www.blueoakranchreserve.org

Contact information:

Rulon Clark <rclark@sciences.sdsu.edu

Hamilton Michael <mphamilton@berkeley.edu

- Posted By: Jaime Adler

- Written by: Sheila Barry, UCCE Advisor Santa Clara County

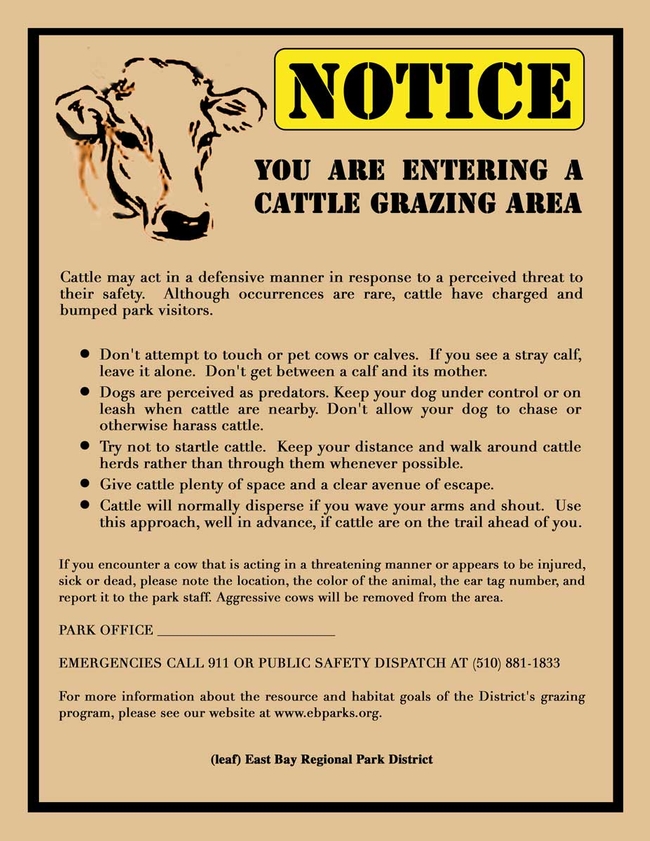

Public land managers and livestock operators often question whether or not open space management objectives including public access for recreation are compatible with livestock grazing. Public concerns ranging from the potential environmental degradation to fear of conflict have led some public land managers to limit or curtail the use of grazing on open spaces public lands. For example in 2009, officials from the City of Walnut Creek decided to end grazing in two parks based on park users’ complaints of cattle trampling trails and “increases in attacks by cattle on dogs and people. Cattle had grazed these parks for decades for weed abatement and the decision came after years of public outcry (TriValley 2009).

Studies have shown that perceptions of livestock use of public lands are associated with type of recreational pursuit, land classification, environmental beliefs, and demographics. Sanderson et al. 1986 found that the more experience recreationalist had on grazed lands the less likely they had negative perceptions of grazing. Brunson and Gilbert 2003 documented that hikers were more likely to feel negatively toward livestock use in a Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument than hunters. Research has also shown rural and urban divide in attitudes and beliefs, especially when the rural economy depends on rangelands. Little is known about the attitudes of the urban public recreating on grazed park lands. In particular how widespread is fear, how is fear dealt with, and how do they feel about “natural landscapes” managed with grazing cattle.

Land managers increasingly recognize the value of grazing as a land management tool (Barry et al., 2007). But where public access is also a priority they must also be able to address public concerns. Land Managers need information about the perceptions that recreational visitors have regarding cattle. By understanding the concerns managers are better equipped to address recreation/grazing conflicts and educate the public.

With the exponential growth in social media and the willingness of people to share ideas with internet communities there is a growing interest in what we can gleem from a photo sharing website like Flickr.comTM. Past efforts to learn from Flickr data have focused largely on tagging and geospatial information (Kennedy et al. 2007). Recent efforts have followed earlier work on understanding the social use of personal photography (Harrison 2004, ) and now, image-sharing (Van House 2007). This project used this rich data set found on Flickr to understand perceptions of cattle grazing on park lands by addressing the following questions:

- When people visit public lands with grazing livestock present, what do they photogragh?

- How do park users respond when they encounter and choose to photograph something seemingly undesirable or potentially frightening i.e. cow pies, a rutted trail, cows on the trail?

Methods

A data set (Table 1) was developed from photos and associated comments posted on Flickr using location and subject as search terms.

Table 1. Data sets developed from Flickr

|

Data sets |

Search terms |

Number of photos |

Number of photographers |

|

|

Location |

Subject |

|||

|

Grazing in Parks |

33 parks in Alameda, Contra Costa, and Santa Clara counties |

cow, cows, grazing |

1087 |

328 |

Photo information in the date set included photo date, posting date, photographer’s name, photo name, photo comments by photographer, posted comments and commenter’s name. Photo titles and all comments were categorized for each data set in the following categories: descriptive, photo quality statement, positive cow, positive grazing, positive landscape, negative cowt, negative landscape, fear (perceived i.e. not based on an actual event), fear (actual i.e. included a description of an event).

Results

When people visit public lands with grazing livestock present, what do they photograph?

More specifically, what do people who post photos from parks with grazing include in photo comments or photograph title?

|

Photo Elements |

Number of photos |

% of photos (n=1087) with this element |

|

Cow(s) |

772 |

.71 |

|

Dogs |

177 |

.16 |

|

Dogs and cow(s) |

31 |

.03 |

|

People |

128 |

.12 |

|

People and cow(s) |

52 |

.05 |

|

Cow pies |

22 |

.02 |

|

Trail |

232 |

.21 |

|

Landscape photo |

728 |

.67 |

How do park users respond when they encounter and choose to photograph and post something seemingly undesirable i.e. cow pies, a rutted trail?

Although 2% of the photos included cows pies in the photos and one picture featured a rutted trail, few comments were made about either of these elements. Comments were matter-of-fact in nature including:

No doubt about it, the cows were here;

Lots of cow poop;

A bumpy path;

How do park users respond when they encounter and choose to photograph and/ or reflect on something potentially frightening (i.e. cows on trails)?

Approximately 5 % (n= 43) of the comments from photos in grazed parks expressed fear of the cattle including comments like these:

I try to conquer my fear of cows by photographing them;

Watch out for those cows;

Got it close to this cow for this shot. You can see she’s giving me the stink eye here so I put the camera away;

The cows scared us to death;

Beware! Mad cows!

This is the cow that blocked our path! Would you want to cross him;

I told them I’m a vegetarian and they let me go;

He wasn’t too keen about being photographed. In addition to the unfriendly stare, he made menacing noises;

A cow that was not happy to see us and almost chased us;

We turned back here as the cow as on the trail path;

We turned around when we were faced with the option of having to walk right through a herd of cows;

Only seven comments ( <1%) included a description of an actual event with “aggressive” animal. These comments described being chased, for example:

Ahh,we were chased last weekend by a young male-err;

At least these cows didn’t chase us like last week’s did;

Happy cows may come from California, but bored cows come from Fremont. I actually tried to have a picnic-but then a bull comes charging us. We got up and ran for our lives. Our bread, cheese and blanket didn’t make it;

How do shared photos and comments from grazed public lands compare to photos and comments from nearby ungrazed public lands?

Overall, most comments could be categorized as descriptive (637 from 934 comments). Examples of descriptive comments include:

- Lots of wildflowers and cows. Hello tiny cows on the hillside.

- Taken at Lake Del Valle.

- Cow pool party.

- I don’t know why but I thought cows in CA where kept indoors. (Points to a need for education!)

- A cow grazing….

- They are pastured to keep the fire danger low

- Cow munchin on some grass near the lake

However there were far more positive cow and grazing comments than negative cow comments ( 126 versus 8).

Positive subject cow and grazing comments included:

- Wonderful to see cows being just cows and happy ones. Beautiful scene.;

- Superb…love the cow;

- Beautiful spring at Morgan Territory. Green grass, clouds and the cows.;

- As much as I struggled over the steep hills on this hike, all the grazing cattle and howling coyotes made it worth the sweat.

- Oh I just love fuzzy winter cows

- Happy cows eating grass not corn

- I went on a really long hike and saw some cool thing from meadows to steephills to trees, cows and interesting rock forms

- Cows happily range over the lands of Sunol Regional Wilderness, keeping down the fuel load

- The sign said that cows have been known to nudge hikers when startled. Its hard to picture a cow nudging a hiker. I doubt that would be the adjective I would use to describe it if I saw it happen. Generally they are scared of hikers and actually help to spread sees, control non-native plants and overall keep a healthy preserve. I kind of like sharing the green hills with them.

Examples of negativecow comments include: it’s a little anti-climatic when you hike uphill for 2 hours and see a herd of cows upon arrival.

- However this kind of landscape also attracts a lot of cows which seem to have more priviledges than me in roaming around

- The only downside was/is that there are cows grazing there a lot and hence: cow patties! Many of the dogs had a taste and all rolled in cow poop quite thoroughly.

Questions to be further analyzed include:

How do shared photos and comments from grazed public lands compare to photos and comments of other subjects that people may find environmentally negative or fearful such as smog or snakes?

How do the type of comments compare to shared photos and comments about other parks with and without grazing?

Discussion and Implications

Is there overwhelmingly negative public opinion towards grazing on public lands as suggested by the article in the TriValley newspaper (Walnut Creek, CA) in 2009? Park users visiting grazed park parks in the Bay Area and sharing their photos didn’t seem to express this opinion. They largely shared descriptions and positive comments about the cattle they saw and the grazed landscape. In addition recent events in Walnut Creek indicate that there is some strong public opinion in support of grazing.. The Contra Costa Times reported in June 2011 that 150 park neighbors in Walnut Creek Open Space park signed a petition that requesting that the cows return to graze the park lands. They neighbors fear potential wildfire from the resulting unmanaged growth of vegetation. The grazing supporters also spoke at a Park Commission meeting where they outnumbered those opposed to the cattle returning 23 to 6.

While park managers have implemented some strategies to reduce public/cattle conflict including signage and timing of grazing, there are undoubtedly opportunities for improved public outreach. Park visitors would benefit from not only understanding the biological value of managed grazing programs but also from better information on livestock behavior and how to interact with livestock they may encounter. Continued education of our urban audience will be essential if livestock grazing is going to continue to be a viable took for managing open space lands.

Literature Cited

Barry, S. T.Schohr, and K. Sweet. 2007. The California Rangeland Conservation Coalition. Rangelands. 29(3):31-34.

Brunson,M. W. and L. Gilbert. 2003. Recreationist responses to livestock grazing in a new national monument. J. Range Manage. 56 (6): 570-576.

Harrison, B. 2004. Snap Happy: Toward a Sociology of “Everyday” Photography. In: C. Pole (Eds), Seeing is Believing? Approaches to Visual Research. Studies of Qualitative Methodolgy, Volume 7: 23-39.

Kennedy, L., M. Naaman, S. Ahern, R.Nair, T. Rattenbury. 2007. How Flickr Helps us Make Sense of the World: Context and Content in Community-Contributed Media Collections. MM’07, September 23-28,2007, Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany.

Sanderson, R.H., R.A. Meganck, and K.C. Gibbs. 1986. Range management and scenic beauty as perceived by dispersed recreationist. J. Range Manage. 39:464-469.

Van House, N. A. 2007. Flickr and Public Image-Sharing: Distant Closeness and Photo Exhibition. CHI 2007, April 28-May 3, 2007, San Jose, CA, USA.