- Author: Royce Larsen

- Editor: Sophie Kolding

Most of the oak woodlands in California are privately owned. The major use of Oak Woodlands is for grazing, primarily for beef cattle. The ranching industry plays an important role in maintaining a sustainable, culturally meaningful, and ecologically rich landscape (Huntsinger and Hopkinson, 1996) in our oak woodlands. Of the many challenges facing ranchers, droughts can be severe.

The great drought of 1862–1865 wreaked havoc on the state and the cattle industry (Burcham, 1957). Since that time we have had severe droughts about 8 times (George et. al. 2010). Even with less severe droughts, cattlemen have a stressful time dealing with changes in forage production. With less forage production, cattlemen either have to reduce herd size, move cattle to other states or locations, or provide extra feed at a great expense. If cattle are sold, it may take several years to build the herd back.

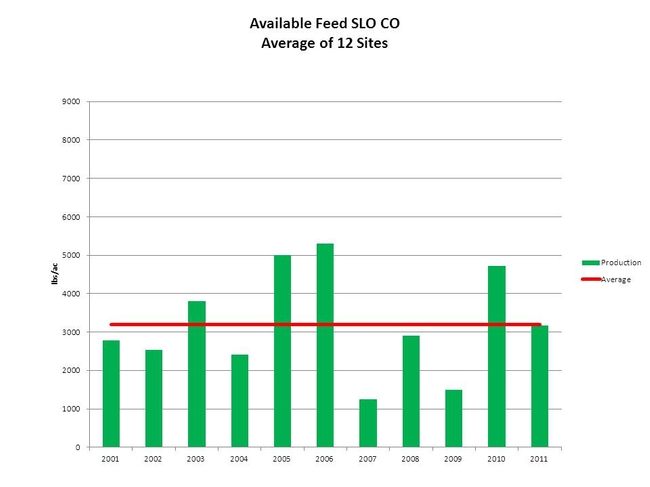

Not all droughts are equal. Droughts tend to be more common in the rain shadow along the Coast Range adjacent to the west edge of the San Joaquin Valley (George et. al. 2010). Even though drought conditions create havoc with management of ranches, ranchers also have to deal with wetter than normal years. There is no such thing as an average year, which makes management decisions very difficult. Forage production and quality can vary greatly from year to year, and is strongly influenced by the timing and amount of rainfall (George et. al. 2001). For example, forage production in San Luis Obispo County over the last 11 years has varied by as much as 4000 lbs/ac (Figure 1). Rainfall amount and timing played a significant role in this variation, which varied by 18 inches of annual precipitation.

Figure 1: Peak Forage Production in San Luis Obispo County from 2001 – 2011.

An average of 12 sites across the county.

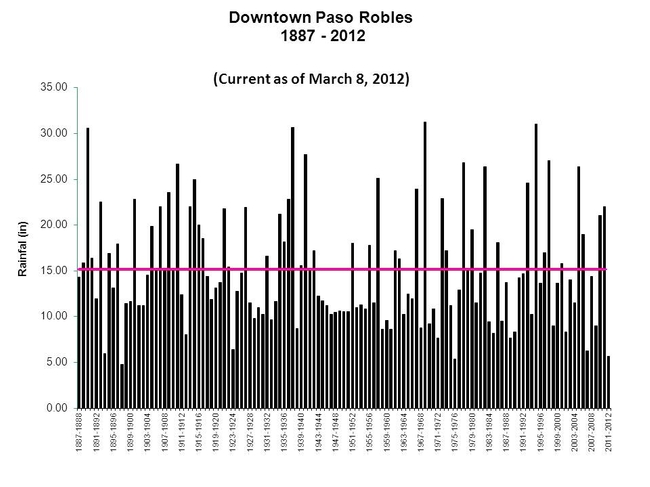

It is just a fact of life that rainfall amount and timing varies. For example, the lowest rainfall recorded in downtown Paso Robles was 4.8 inches in 1898 (Figure 2). The highest recorded was 31.3 inches in 1969, the year of the big flood. It is important to notice that 6 out 10 years are below average (Figure 2). This means that the four years that are above average are usually wet years, which often produces extra forage. For more practical purposes, the years that are below the average determine what and how much forage can be produced on a ranch, which determines the number of cattle that can be grazed on a sustainable basis. It is very important to the ecological health of the oak woodlands / grasslands to maintain proper stocking rates to achieve the desired grazing level. Maintaining the proper amount of residual dry matter (RDM) has become the standard to determine grazing use on oak woodlands and annual grasslands. Properly managed RDM provides protection from soil erosion and nutrient losses, and also plays an important role determining the following year’s production and composition of species (Bartolome et. al. 2006). To accomplish this requires constant change in management by ranchers. I applaud those ranchers who work so hard to accomplish this.

Figure 2: Rainfall records at the down town Paso Robles. Data is based on water

year July 1 – June 30. Average precipitation is 15 in/yr.

Below are images taken of the peak forage production for San Luis Obispo County:

Spring 2006 normal, wet conditions

Soda Lake Site Cambria Site

Spring 2007 drought conditions

Soda Lake Site Cambria Site

References

Burcham, L.T. 1957. California range land: An historico-ecological study of the range resource of California. Division of Forestry, Department of Natural Resources, State of California, Sacramento, California, USA.

Bartolome, J.W., W.E. Frost, N.K. McDougald, and M. Connor. 2006. California guidelines for residual dry matter (RDM) management on the coastal and foothill annual rangelands. Oakland, CA USA: Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California, Publication 8092.

Huntsinger, L. and P. Hopkinson. 1996. Viewpoint: Sustaining rangeland landscapes: a social and ecological process. Journal of Range Management 49(2):167-173.

George, M.R., R.E. Larsen, N.M. McDougald, C.E. Vaughn, D.K. Flavell, D.M. Dudley, W.E. Frost, K.D. Striby, and L.C. Forero. 2010. Determining Drought on California’s Mediterranean-Type Rangelands: The Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program. Rangelands 32(3):16-20.

- Posted By: Sophie Kolding

- Written by: Jim Sullins and John Maas

Four head mature cows have been reported dead in Tulare County foothills from 2500 feet to 1000 foot elevations. All were in the vicinity of Blue Oaks with heavy crop of acorns.

Neil McDougald, Livestock Range Advisor of Madera County indicated that this year is similar to other years he has seen where there have been incidents of acorn toxicity. There is a very large acorn crop, and recent rains has led to some early green-up under Oak Trees which can result in some cows camping and eating an overload of acorns resulting in acorn poisoning.

Most cattle in California spend at least part of the year in areas where oak trees abound. Health problems due to ingestion of oak leaves or acorns are certainly not an everyday problem; however, when problems do occur they can be catastrophic. Several years ago, in a few northern California counties, about 2,700 cattle died due to oak toxicity1.

Some years have much higher production of oak acorns than others and this year, 2011 in the Foothill Ranges of the Southern Sierras, has been reported as one of the highest production years observed. In addition early rains may increase the risk of acorns by reducing the nutrient value of last year’s forage, as well as causing an early greening of grass under the oaks where acorns are accumulating.

During the week of October 10, 2011 four head mature cows were reported to be found dead in Tulare County foothills from 2500 feet to 1000 foot elevations. All were in the immediate vicinity of Blue Oaks with heavy crop of acorns. These cattle were not available for necropsy and cause of death was not confirmed, however oak acorn toxicity is suspected.

Oak toxicity symptoms usually appear when cattle eat 50% or more of their diet as oak (acorns, leaves, buds). Toxicity can be prevented by supplementing cattle with hay or other supplements when forage conditions are poor and acorns are abundant. A higher risk may occur if early or late snowstorms covers available forage and knocks down oak limbs with large amounts of buds and young leaves or acorns, be sure to start hay supplementation immediately. A delay of only a day or two could result in many deaths.

There are two recommendations to avoid cattle loss due to acorn toxicity. One is to provide supplement to draw cattle away from the acorns, so that their exposure decreases. The other is to remove cattle observed eating acorns from fields with high levels of acorns.

It is recommended that producers work with their local veterinarian and/or diagnostic laboratory, to be certain of the actual cause of death in all livestock losses. There are many other factors that can cause sudden death and although oak toxicity may be likely and immediate actions should be taken to prevent further deaths, a follow up with a veterinarian is often the best course of action to prevent further losses. For a more comprehensive discussion on identification and recommended actions for Oak Toxicity and Acorn Calf syndrome in cattle please refer to the link below.

Dr. John Maas, UC Davis Extension Veterinarian, informative article on oak toxicity (OAK TOXICITY UCD Vet Views California Cattleman, Jan 2001):

http://www.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/vetext/INF-BE_cca/INF-BE_cca01/INF-BE_cca0101.html. Blue Oak Acorn

Blue Oak Acorn

Cattle Pasture amongst Blue Oaks

- Posted By: Jaime Adler

- Written by: Sheila Barry, UCCE Advisor Santa Clara County

Public land managers and livestock operators often question whether or not open space management objectives including public access for recreation are compatible with livestock grazing. Public concerns ranging from the potential environmental degradation to fear of conflict have led some public land managers to limit or curtail the use of grazing on open spaces public lands. For example in 2009, officials from the City of Walnut Creek decided to end grazing in two parks based on park users’ complaints of cattle trampling trails and “increases in attacks by cattle on dogs and people. Cattle had grazed these parks for decades for weed abatement and the decision came after years of public outcry (TriValley 2009).

Studies have shown that perceptions of livestock use of public lands are associated with type of recreational pursuit, land classification, environmental beliefs, and demographics. Sanderson et al. 1986 found that the more experience recreationalist had on grazed lands the less likely they had negative perceptions of grazing. Brunson and Gilbert 2003 documented that hikers were more likely to feel negatively toward livestock use in a Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument than hunters. Research has also shown rural and urban divide in attitudes and beliefs, especially when the rural economy depends on rangelands. Little is known about the attitudes of the urban public recreating on grazed park lands. In particular how widespread is fear, how is fear dealt with, and how do they feel about “natural landscapes” managed with grazing cattle.

Land managers increasingly recognize the value of grazing as a land management tool (Barry et al., 2007). But where public access is also a priority they must also be able to address public concerns. Land Managers need information about the perceptions that recreational visitors have regarding cattle. By understanding the concerns managers are better equipped to address recreation/grazing conflicts and educate the public.

With the exponential growth in social media and the willingness of people to share ideas with internet communities there is a growing interest in what we can gleem from a photo sharing website like Flickr.comTM. Past efforts to learn from Flickr data have focused largely on tagging and geospatial information (Kennedy et al. 2007). Recent efforts have followed earlier work on understanding the social use of personal photography (Harrison 2004, ) and now, image-sharing (Van House 2007). This project used this rich data set found on Flickr to understand perceptions of cattle grazing on park lands by addressing the following questions:

- When people visit public lands with grazing livestock present, what do they photogragh?

- How do park users respond when they encounter and choose to photograph something seemingly undesirable or potentially frightening i.e. cow pies, a rutted trail, cows on the trail?

Methods

A data set (Table 1) was developed from photos and associated comments posted on Flickr using location and subject as search terms.

Table 1. Data sets developed from Flickr

|

Data sets |

Search terms |

Number of photos |

Number of photographers |

|

|

Location |

Subject |

|||

|

Grazing in Parks |

33 parks in Alameda, Contra Costa, and Santa Clara counties |

cow, cows, grazing |

1087 |

328 |

Photo information in the date set included photo date, posting date, photographer’s name, photo name, photo comments by photographer, posted comments and commenter’s name. Photo titles and all comments were categorized for each data set in the following categories: descriptive, photo quality statement, positive cow, positive grazing, positive landscape, negative cowt, negative landscape, fear (perceived i.e. not based on an actual event), fear (actual i.e. included a description of an event).

Results

When people visit public lands with grazing livestock present, what do they photograph?

More specifically, what do people who post photos from parks with grazing include in photo comments or photograph title?

|

Photo Elements |

Number of photos |

% of photos (n=1087) with this element |

|

Cow(s) |

772 |

.71 |

|

Dogs |

177 |

.16 |

|

Dogs and cow(s) |

31 |

.03 |

|

People |

128 |

.12 |

|

People and cow(s) |

52 |

.05 |

|

Cow pies |

22 |

.02 |

|

Trail |

232 |

.21 |

|

Landscape photo |

728 |

.67 |

How do park users respond when they encounter and choose to photograph and post something seemingly undesirable i.e. cow pies, a rutted trail?

Although 2% of the photos included cows pies in the photos and one picture featured a rutted trail, few comments were made about either of these elements. Comments were matter-of-fact in nature including:

No doubt about it, the cows were here;

Lots of cow poop;

A bumpy path;

How do park users respond when they encounter and choose to photograph and/ or reflect on something potentially frightening (i.e. cows on trails)?

Approximately 5 % (n= 43) of the comments from photos in grazed parks expressed fear of the cattle including comments like these:

I try to conquer my fear of cows by photographing them;

Watch out for those cows;

Got it close to this cow for this shot. You can see she’s giving me the stink eye here so I put the camera away;

The cows scared us to death;

Beware! Mad cows!

This is the cow that blocked our path! Would you want to cross him;

I told them I’m a vegetarian and they let me go;

He wasn’t too keen about being photographed. In addition to the unfriendly stare, he made menacing noises;

A cow that was not happy to see us and almost chased us;

We turned back here as the cow as on the trail path;

We turned around when we were faced with the option of having to walk right through a herd of cows;

Only seven comments ( <1%) included a description of an actual event with “aggressive” animal. These comments described being chased, for example:

Ahh,we were chased last weekend by a young male-err;

At least these cows didn’t chase us like last week’s did;

Happy cows may come from California, but bored cows come from Fremont. I actually tried to have a picnic-but then a bull comes charging us. We got up and ran for our lives. Our bread, cheese and blanket didn’t make it;

How do shared photos and comments from grazed public lands compare to photos and comments from nearby ungrazed public lands?

Overall, most comments could be categorized as descriptive (637 from 934 comments). Examples of descriptive comments include:

- Lots of wildflowers and cows. Hello tiny cows on the hillside.

- Taken at Lake Del Valle.

- Cow pool party.

- I don’t know why but I thought cows in CA where kept indoors. (Points to a need for education!)

- A cow grazing….

- They are pastured to keep the fire danger low

- Cow munchin on some grass near the lake

However there were far more positive cow and grazing comments than negative cow comments ( 126 versus 8).

Positive subject cow and grazing comments included:

- Wonderful to see cows being just cows and happy ones. Beautiful scene.;

- Superb…love the cow;

- Beautiful spring at Morgan Territory. Green grass, clouds and the cows.;

- As much as I struggled over the steep hills on this hike, all the grazing cattle and howling coyotes made it worth the sweat.

- Oh I just love fuzzy winter cows

- Happy cows eating grass not corn

- I went on a really long hike and saw some cool thing from meadows to steephills to trees, cows and interesting rock forms

- Cows happily range over the lands of Sunol Regional Wilderness, keeping down the fuel load

- The sign said that cows have been known to nudge hikers when startled. Its hard to picture a cow nudging a hiker. I doubt that would be the adjective I would use to describe it if I saw it happen. Generally they are scared of hikers and actually help to spread sees, control non-native plants and overall keep a healthy preserve. I kind of like sharing the green hills with them.

Examples of negativecow comments include: it’s a little anti-climatic when you hike uphill for 2 hours and see a herd of cows upon arrival.

- However this kind of landscape also attracts a lot of cows which seem to have more priviledges than me in roaming around

- The only downside was/is that there are cows grazing there a lot and hence: cow patties! Many of the dogs had a taste and all rolled in cow poop quite thoroughly.

Questions to be further analyzed include:

How do shared photos and comments from grazed public lands compare to photos and comments of other subjects that people may find environmentally negative or fearful such as smog or snakes?

How do the type of comments compare to shared photos and comments about other parks with and without grazing?

Discussion and Implications

Is there overwhelmingly negative public opinion towards grazing on public lands as suggested by the article in the TriValley newspaper (Walnut Creek, CA) in 2009? Park users visiting grazed park parks in the Bay Area and sharing their photos didn’t seem to express this opinion. They largely shared descriptions and positive comments about the cattle they saw and the grazed landscape. In addition recent events in Walnut Creek indicate that there is some strong public opinion in support of grazing.. The Contra Costa Times reported in June 2011 that 150 park neighbors in Walnut Creek Open Space park signed a petition that requesting that the cows return to graze the park lands. They neighbors fear potential wildfire from the resulting unmanaged growth of vegetation. The grazing supporters also spoke at a Park Commission meeting where they outnumbered those opposed to the cattle returning 23 to 6.

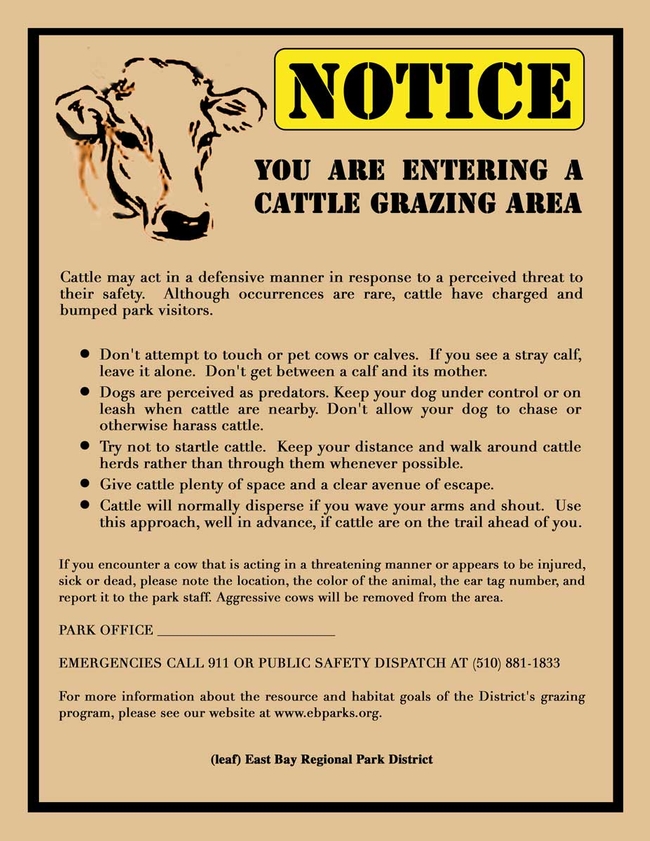

While park managers have implemented some strategies to reduce public/cattle conflict including signage and timing of grazing, there are undoubtedly opportunities for improved public outreach. Park visitors would benefit from not only understanding the biological value of managed grazing programs but also from better information on livestock behavior and how to interact with livestock they may encounter. Continued education of our urban audience will be essential if livestock grazing is going to continue to be a viable took for managing open space lands.

Literature Cited

Barry, S. T.Schohr, and K. Sweet. 2007. The California Rangeland Conservation Coalition. Rangelands. 29(3):31-34.

Brunson,M. W. and L. Gilbert. 2003. Recreationist responses to livestock grazing in a new national monument. J. Range Manage. 56 (6): 570-576.

Harrison, B. 2004. Snap Happy: Toward a Sociology of “Everyday” Photography. In: C. Pole (Eds), Seeing is Believing? Approaches to Visual Research. Studies of Qualitative Methodolgy, Volume 7: 23-39.

Kennedy, L., M. Naaman, S. Ahern, R.Nair, T. Rattenbury. 2007. How Flickr Helps us Make Sense of the World: Context and Content in Community-Contributed Media Collections. MM’07, September 23-28,2007, Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany.

Sanderson, R.H., R.A. Meganck, and K.C. Gibbs. 1986. Range management and scenic beauty as perceived by dispersed recreationist. J. Range Manage. 39:464-469.

Van House, N. A. 2007. Flickr and Public Image-Sharing: Distant Closeness and Photo Exhibition. CHI 2007, April 28-May 3, 2007, San Jose, CA, USA.