- Editor: Sophie Kolding

- Author: Jan Gonzales

The goldspotted oak borer (GSOB; Agrilus auroguttatus) continues to attack and contribute to the high mortality of tens of thousands of oaks in San Diego County and the threat to oaks throughout southern California remains a considerable concern. In effort to inform professionals who are responsible for the stewardship of oaks and oak woodlands, a series of workshops has been offered in six southern California counties in which oaks may be at risk: Ventura, Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, Orange and San Diego. The overlying objective was to spread the knowledge of goldspotted oak borer and minimize the spread of this non-native insect into new areas. These day-long events offered multi-agency presentations, hands-on displays, outreach materials and in some locations, short field trips.

Figure 1. Dead oak trees due to GSOB Figure 2. Two Adult GSOB on penny

(Photo source: Tom Coleman, USDA Forest Service) (Photo source: Tom Coleman, USDA Forest Service)

In cooperation, the USDA Forest Service, CAL FIRE, and the University of California have partnered with other local agencies, tribes and organizations to provide these workshops. Presenters at each session were coordinated from a cadre of specialists and researchers. Key speakers included Tom Coleman, Paul Zambino, Sheri Smith, Larry Swann, Lisa Fischer and Matthew Bokach (USDA Forest Service and Forest Health Protection); Tom Smith, Kim Camilli and Kathleen Edwards (CAL FIRE);Tom Scott, Doug McCreary, Jim Downer and Kevin Turner (University of California Cooperative Extension); and Vanessa Lopez (PhD candidate in the Entomology Department, UC Riverside). Introductory workshops were held monthly from September 2010 through February 2011. Topics covered were:

- GSOB history and distribution

- GSOB identification and biology

- Ecological and economic impacts of infested oaks and oaks at-risk

- Integrated best management practices for GSOB infested and at-risk oak woodlands

- How to prepare for potential outbreak

- Utilization of GSOB infested oak wood

- Restoring oak woodlands impacted by GSOB

Figure 3. Larvae Feeding Galleries, seen in cambium Figure 4. GSOB larvae in firewood (Photo source:

of oak wood cross-section (Photo source: Tom Scott, UC Cooperative Extension)

Kim Camilli, CAL FIRE)

In early May 2012, two additional workshops were held to provide updates from on-going research, best management practices and mitigation and education efforts. The session on May 1st was held in Altadena in partnership with the Los Angeles County Fire Department-Forestry Division and the County Parks and Recreation Department. The following workshop, held on May 2nd, was hosted in partnership with the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians in Temecula.

Information Highlights:

- The goldspotted oak borer in an introduced, non-native beetle attacking and killing coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), California black oak (Quercus kelloggii), and canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis) trees in San Diego County.

- The adult goldspotted oak borer (GSOB) Agrilus auroguttatus is a small, bullet-shaped beetle about 10mm (0.4 in.) long and has six golden yellow spots on its dark green forewings.

- Mature larvae are white, legless, slender and about 18mm (0.75 in.) long with two pincher-like spines at the tip of the abdomen. Larvae feed under the bark on the trunk and larger branches.

- Larval feeding kills patches and strips of cambium tissue beneath the bark, which causes dark staining and sap flow. The larvae pupate in the outer bark and leave D-shaped exit holes about 1/8 in. wide when they emerge.

- GSOB produce only one beetle generation per year.

- The goldspotted oak borer’s peak flight and breeding season is May through October.

- There is on-going research being conducted on biological and chemical GSOB control methods for preventative management; trees at various degrees of infestation; and the wood from infested, dead and felled trees.

- Currently, there are no effective treatments that can eradicate GSOB once it becomes established.

- Goldspotted oak borer larvae and pupae can survive under the bark of wood from large branches and trunks for up to a year after a tree dies.

- Currently, best management practices to minimize introduction of GSOB to new areas is to let wood cure at least two years after the tree dies before moving firewood from infested areas or grind wood into 3-inch particles.

- Before any type of treatment on oaks is initiated for GSOB infested trees or as a preventative measure on high-valued trees, a management plan should be developed first.

- There are no quarantines or zones of infestation in place by statewide authorities for GSOB; however, in 2011 the California Pest Council established the California Firewood Taskforce, a coalition of stakeholders that initiates and facilitates efforts within the state to protect our native and urban forests from invasive pests that can be moved on firewood.

- The Early Warning System is a citizen scientist program established to enlist the help of those concerned about oaks for the purpose of identifying oak tree health in southern California urban and woodland areas.

- Information and resources may be found on the Goldspotted Oak Borer website, www.gsob.org. To stay informed of current news, information and future training opportunities, we recommend you join the GSOB email list.

(Photo source: Lorin Lima, UC Cooperative Extension-San Diego)

Nearly 500 professionals attended these workshops. Findings from follow-up workshop surveys indicate that potentially more than 2,600 others will learn about GSOB through outreach extended by workshop participants. Although evaluation and survey responses point towards a successful series of GSOB workshops, the threat of further goldspotted oak borer attacks remains. As the peak emergence and flight season occurs during the same time of year of increased vacation travel and camping in southern California, we are all encouraged to share the news about GSOB and it’s threat to oaks with others along with the message to not move firewood – “Buy It Where You Burn It.”

For more information:

Goldspotted Oak Borer website: http://www.gsob.org

California Firewood Task Force: http://www.firewood.ca.gov

Goldspotted Oak Borer - The Center for Invasive Species Research, UC Riverside:

http://cisr.ucr.edu/goldspotted_oak_borer.html

Goldspotted Oak Borer – UC Statewide Integrated Pest Management: http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/NATURAL/index.html

- Posted By: Sophie Kolding

- Written by: Tom Scott

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – A catastrophic infestation of the goldspotted oak borer, which has killed more than 80,000 oak trees in San Diego County in the last decade, might be contained by controlling the movement of oak firewood from that region, according to researchers at the University of California, Riverside.

“This may be the biggest oak mortality event since the Pleistocene (12,000 years ago),” said Tom Scott, a natural resource specialist. “If we can keep firewood from moving out of the region, we may be able to stop one of the biggest invasive pests to reach California in a long time.”

A cadre of UC researchers is leading the effort to assess and control the unprecedented infestation, in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service. Scott and others are working to identify where the infestation began, how it is spreading through southern California’s oak woodlands, and what trees might be resistant. In October 2010 Scott and other UCR researchers received $635,000 of a $1.5 million grant of federal stimulus money awarded to study the goldspotted oak borer and sudden oak death.

The goldspotted oak borer (Agrilus auroguttatus), which is native to Arizona but not California, likely traveled across the desert in a load of infested firewood, possibly as early as the mid-1990s, Scott said. Researchers have confirmed the presence of the beetle as early as 2000 near the towns of Descanso and Guatay, where nearly every oak tree is infested.

The half-inch-long beetle attacks mature coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), California black oaks (Quercus kelloggii) and canyon live oaks (Quercus chrysolepis). Female beetles lay eggs in cracks and crevices of oak bark, and the larvae burrow into the cambium of the tree to feed, irreparably damaging the water- and food-conducting tissues and ultimately killing the tree. Adult beetles bore out through the bark, leaving a D-shaped hole when they exit.

Scott and Kevin Turner, goldspotted oak borer coordinator for UC Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) at UCR, said that field studies in San Diego County in the last six months point strongly to the transportation of infested oak firewood as the source of the invasion that threatens 10 million acres of red oak woodlands in California.

Outbreaks have been found 20 miles from the infestation area, implicating firewood as the most likely reason for the beetle infestation leap-frogging miles of healthy oak woodlands to end up in places like La Jolla. In contrast, communities that harvest their own trees for firewood have remained relatively beetle-free, even as adjacent areas suffer unprecedented rates of oak mortality. Both examples support the growing conviction that the movement of infested firewood is the primary means by which the beetles are spreading, Scott said.

California’s coast live oaks, black oaks and canyon live oaks seem to have no resistance to the goldspotted oak borer and, so far, no natural enemies of the beetle have been found in the state.

The devastation can be measured in costs to communities and property owners for tree removal, the loss of recreation areas and wildlife habitat, lower property values and greater risk of wildfires. The three oaks under attack may be the single most important trees used by wildlife for food and cover in California forests and rangelands.

Most of the dead and dying trees are massive, with trunks 5 and 6 feet in diameter, and are 150 to 250 years old. The cost of removing one infested tree next to a home or in a campground can range from $700 to $10,000. The cost of removing dead and dying trees in San Diego County alone could run into the tens of millions of dollars. In Ohio, which has experienced similar losses from the emerald ash borer, several small cities went bankrupt because of tree removal costs associated with that beetle, Scott said.

So many oaks have died in the Burnt Rancheria campground on the Cleveland National Forest – a favorite spot for campers who favored the shade of a dense canopy of coast live oaks – that the Forest Service has had to erect shade structures. Other state and county parks in the region have suffered equally devastating losses.

Turner said an Early Warning System of community volunteers launched in San Diego County now includes representatives from every southern California county as far north as Ventura. Those volunteers are trained to monitor the health of oak trees in their communities and report any unusual changes.

At the same time, a network of UC Cooperative Extension, ANR, U.S. Forest Service and other agencies in the region is working with woodcutters, arborists and consumers to discourage the sale and transportation of infested wood. Wood that is bark-free or that has dried and cured for at least one year is generally safe to transport, Scott said. This relatively small change in firewood-handling methods could save a statewide resource without jeopardizing the firewood industry, he said.

Local, state and federal agencies recognize that firewood production is one of the least-regulated industries in California, and view UC Cooperative Extension education as the best means of stopping goldspotted oak borer movement in firewood.

“Quarantines don’t work, but enlightened self-interest can keep oak woodland residents from importing GSOB-infested firewood,” Scott said. “This is a situation where the university can play a critical role in changing behavior through research and education rather than regulation.”

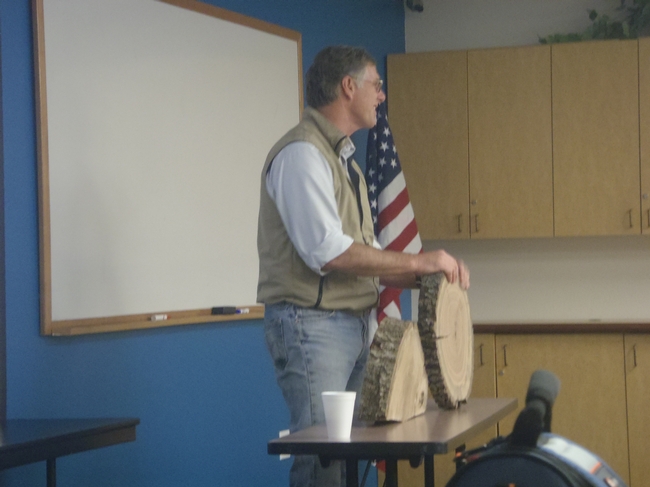

A cross-section of an oak infested by the goldspotted oak borer shows the damage done by the non-native beetle.

To view original article, Click Here.

Related Links:

Goldspotted Oak Borer Information

GSOB Research at UCR

UC Cooperative Extension