- Author: Kathy Keatley Garvey

The drama unfolds slowly.

The crafty praying mantis that's perched atop a zinnia raises its spiked, grasping forelegs and silently waits for unsuspecting prey.

A sweat bee cruises by. Then a second one. Then a third.

They do not land and the praying mantis does not move.

Is it possible for an insect to be as still as a statue? It is. Praying mantids can lie in wait for hours. When their prey comes near, they lash out and grab it, holding it in their spiked forelegs while they eat it alive.

Meanwhile, this praying mantis in the Häagen-Dazs Honey Bee Haven, a half-acre pollinator garden on Bee Biology Road, University of California, Davis, doesn't have long to wait. A honey bee lands on the predator's perch.

A predator. A prey. A pollinator garden.

The bee crawls slowly along the blossoms and is just about to forage when it spots the predator.

In a flurry of wings and legs, almost faster than a 1/640th-of-a-second shutter speed, the praying mantis lunges. Nothing but air! The bee escapes (probably in a "shudder" speed) and buzzes away.

This meal was not to bee.

- Author: Kathy Keatley Garvey

Varroa mites, those pesky little parasites that suck the blood out of honey bees and spread multiple viruses, are now found throughout the world, except in Australia.

Scientists blame these parasites as one of the causes of colony collapse disorder (CCD), characterized by adult bees abandoning the hive and leaving behind the queen, brood and food stores. They attribute CCD to a multitude of factors, including pests, pesticides, parasites, diseases, viruses, malnutrition and stress. Thus, varroa mites are a key factor in the declining honey bee population.

Today's honey bees are ill-equipped to rid their hives of a varroa mite infestation. Indeed, beekeepers consider the varroa mite (scientific name Varroa destructor) as Public Enemy No. 1.

And that's one of the reasons why we like bee breeder-geneticist Susan Cobey's efforts to increase the genetic diversity in our domestic honey bee gene pool.

Cobey, who has a dual appointment at the University of California, Davis and Washington State University, is directing a stock improvement program which aims to do just that.

"Increasing the overall genetic diversity of honey bees will lead to healthier and hardier bees that can better fight off parasites, pathogens and pests," she says.

"We have collected and imported honey bee semen (germplasm) from their original European homeland to inseminate select domestic queens produced by the California bee breeders," Cobey told us. These California breeders supply queen bees and package bees nationwide. Honey bees, as Cobey points out, "provide the essential pollination for our crops, especially in California, "the breadbasket" of our country and our world.

Cobey and her team have also re-introduced the subspecies, Apis mellifera caucasica, a dark race of bee known for its collection and use of propolis, self-medicating plant resins.

What does a mite look like? Check out the mite-infested drone below. A boy bee's only duty is to gather in the drone congregation area and mate with the queen during her maiden flight, but that won't happen with this one. No thanks to the parasitic mites, he has a weakened immune system, crippling his ability to fly.

What will happen to him? His sisters will kick him out of the hive and he will die.

- Author: Kathy Keatley Garvey

When California poppies (Eschscholzia californica) bloom and honey bees battle over the blossoms, can spring be far behind?

No, it's just California's pleasant weather. The California poppy, the state flower, usually blooms from February to September, but sometimes in a warm, sheltered area, you'll find it blooming in the dead of winter--and honey bees foraging among the blossoms.

Such is the case over on Garrod Drive by the UC Davis Arboretum Teaching Nursery. The asphalt from the parking lot generates quite a big of heat--and coupled with the sun, that's plenty of warmth for golden poppies to flourish.

It's a sight to bee-hold when Apis mellifera and Eschscholzia californica meet in December.

- Author: Kathy Keatley Garvey

In the bug world, we're all grateful for the people who study insects, monitor them, and share information to impart scientific data and help save declining species.

Take butterfly expert Art Shapiro, professor of ecology and evolution at the University of California, Davis (of Art's Butterfly World).

How he does it, we'll never know, but he has monitored butterflies in the area for more than three decades and knows when a population is declining or increasing.

On a trip to Vacaville on Nov. 12, Shapiro discovered six gulf fritillaries (Agraulis vanillae) in gardens on Buck Avenue, and one at the base of Gates Canyon (that's only the second he's seen; the first he saw in May of 1984).

That's great news!

"I suspect the colony has expanded into the upscale hillside neighborhood off Foothill but had no time to go looking," Shapiro commented.

Meanwhile, he says, there are fewer gulf frits in Sacramento this year than in the last two years.

The gulf frit is one of the showiest butterflies in California. The bright orange-red butterfly, with a wingspan that can reach four inches, was first recorded in the Bay Area before 1908. Shapiro says it became established there only in the 1950s.

The last time we saw gulf frits in Vacaville was a couple of months ago, on Sept. 14. They were all over a passionflower vine (Passiflora)--the adults, the pupae, the larvae and the eggs--in a Buck Avenue garden. Later we saw several nectaring lantana.

Now they appear to be expanding their territory in Vacaville.

We all ought to be attracting them! The larval hosts include passionflower vines, such as the maypop (Passiflora incarnata), blue passionflower (P. caerulea), and corky-stemmed passionflower (P. suberosa). As an adult, the gulf frit nectars on such plants as lantana (Lantana camara), tall verbena (Verbena bonariensis), pentas (Pentas lanceolata), drummond phlox (Phlox drummondi) and something called "tread softly" (Cnidosculous stimulosus).

- Author: Kathy Keatley Garvey

Until recently, praying mantids were thought to be deaf. We now know that 65 percent of all mantid species can hear. Where do the tympanal organs occur in mantid species?

Give up?

The answer: The two tympanal membranes face one another inside a narrow groove between the metathoracic legs (hind legs).

That was just one of the questions asked at the 2011 Linnaean Games, a traditional part of the annual meetings of the Entomological Society of America (ESA). It's a spirited college-bowl type of game in which students respond by ringing a bell and shouting out the answers. The winning team receives a huge trophy--and bragging rights.

The UC Davis Linnaean Team, fresh from winning the ESA Pacific Branch championship, journeyed to Reno to compete in this year's Games. Like the other branch winners, UC Davis was there not just to compete, but to have fun and enjoy the camaraderie.

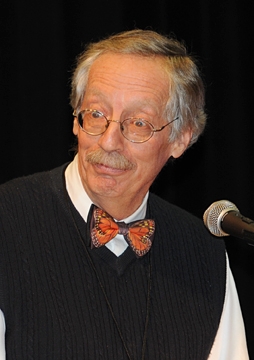

Fun, they did. For the occasion, emcee Tom Turpin, professor of entomology at Purdue, wore his trademark butterfly bow tie. His sharp eyes quickly noticed the bright red bow tie of UC Davis graduate student Matan Shelomi.

So Turpin leaves the podium and walks over to Shelomi to congratulate him on his fashionable choice of ties. The audience erupts into applause.

Then, let the Games begin! When it was all over, the University of Nebraska took home the trophy.

In the championship game, pitting Nebraska against North Carolina State, it was touch-and-go for awhile until Nebraska pulled solidly ahead.

Think you can answer some of the questions? Give them a try. (Answers below)

1.If you donate blood, you are asked about your exposure to babesiosis. What is the common name of the arthropod group that is the main vector of this disease?

2. What is the term for the separation of the cuticle from the epidermis during molting?

3. What does acuminate mean?

4. What is the common and scientific name of the beetle described by LeConte that is a significant pest of corn and was introduced into Europe in the 1990s. The larvae feed on corn roots.

5. What is the meaning of rugose?

6. Most ants use chemical trailing to navigate to and from the nest. However, as a result of high winds and blowing sand, ants that inhabit dessert environments use a different mechanism. How do desert ants find their way?

7. What is the name of insecticidal extract derived from dried chrysanthemum flowers and what chemical is typically added as a synergist to help the performance of this material?

Answers:

1. Ticks

2. Apolysis

3. Tapering to a long point.

4. Western Corn Rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera)

5. Wrinkled

6. They have the ability to count steps. A recent study experimentally altered the length of ant legs after their search for food. They found that ants with longer legs overshot the nest while ants with their legs shortened didn’t go all the way back to the nest. They then placed all the ants in the nest, and the next day all ants went out in search of food and came exactly back to the nest, showing that desert ants have some kind of pedometer. Source: http://www.entsoc.org/buzz/ants-count

7. Pyrethrum – Piperonyl butoxide.