- Posted By: Chris M. Webb

- Written by: Mary Bianchi

We’d like to challenge you to take the following quiz. Take a minute to place a check mark next to all the practices you regularly employ in your operation. Go ahead – we won’t be collecting them!

Part 1

Yes/ No I know what the nitrogen requirements (lbs actual N/acre/year or /tree/year) are for my crops

Yes/ No I know what the nitrogen levels are in soil amendments I use in my operation (compost, manure, crop residues, etc.)

Yes/ No I have lab analysis of my well/irrigation water.

Yes/ No I monitor tissue levels of nitrogen in my crops to help with fertilizer decisions.

Yes/ No I have put together a nutrient budget that considers all sources of nitrogen for the crops I produce.

Part 2

Yes/ No When I do apply nitrogen, applications are timed according to crop requirements.

Yes/ No I use fertigation to apply nitrogen.

Yes/ No Applications of nitrogen are split into smaller doses to improve efficiency of uptake.

Yes/ No I use cover crops that help manage nitrogen availability.

Yes/ No I manage irrigations to avoid nutrient loss below the rootzone of the crop.

If you marked yes to these as regular activities, you’ve just taken steps in showing how your production decisions can protect water quality. The combined activities noted in Part 1 constitute a Management Practice that protects water quality by developing a nutrient budget to help apply only the appropriate amounts of fertilizer. Activities in Part 2 may alone or in combination constitute Management Practices that help ensure fertilizers are applied efficiently.

Every grower uses ‘management practices’, many of which are meant to generate the best possible product for market. Depending on who you’re talking with, the term ‘management practice’ can be something your Farm Advisor recommends (i.e., pruning to control tree height), your produce buyer suggests (protect avocados in bins from sun scald), or the term can have regulatory connotations.

You’ve all probably heard the term Best Management Practices. Best Management Practice (BMP) is defined in the Federal Clean Water Act of 1987, as “a practice or combination of practices that is determined by a state to be the most effective means of preventing or reducing the amount of pollution generated by nonpoint sources to a level compatible with water quality goals.” The term “best” is subject to interpretation and point of view. In recognition of this, the Coastal Zone Reauthorization Amendment (2000) substituted the terms Management Measures and Management Practices.

How can you tell if any individual activity constitutes a Management Practice that meets the needs of a regulatory program to protect water quality? Ask yourself this question: Can the activity stand alone and result in water quality benefits? Just knowing the nitrogen requirements of your crop doesn’t result in any water quality benefits – developing and using a nitrogen budget for your crop can. A nitrogen budget that takes into account the nutrients applied in amendments, irrigation water, and fertilizers in meeting the requirements of your crop does have the potential to protect water quality from nitrogen pollution from your operation.

Some Management Practices can have water quality benefits as a stand alone activity. Cover crops are recognized as a Management Practice that can help manage both sediment and nutrients to reduce the potential of pollution when used appropriately.

Water quality protection is being asked of all industries in California. You have the opportunity to take credit for all of the activities you already do, like the ones listed above, that protect your local water bodies and/or groundwater from nonpoint source pollution from your operation. Look for additional articles in the coming issues to help you in this effort.

For additional background information on water quality legislation, and nonpoint source pollution from agriculture you can download the following free publications from the University of California’s Farm Water Quality Program:

Water Pollution Control Legislation

Nonpoint Sources of Pollution from Irrigated Agriculture

- Posted By: Chris M. Webb

- Written by: Ben Faber

Introduction

In numerous publications world-wide, planting hole recommendations for avocado and other subtropical crops are made for large holes from 2 feet by 2 by 2 to as much as a cubic yard. These recommendations also include incorporation of manures or composts comprising 25% by volume with the native soil. I have noted the use of large holes and amendments in several countries, including New Zealand, Guatemala, Brazil, Costa Rica, Mexico and the United States.

The various reasons given for making these large holes are to disrupt any compaction or limiting soil layers and to create a more conducive environment for root growth. In the case of replanting deciduous orchards, McKenry found it to be beneficial in actually replacing the native soil in the hole with pathogen free soil. In many cases, research has shown that holes much larger than the planting ball and using organic amendments can cause problems for many tree species. Improper mixing of the organic amendment can cause anaerobic conditions and settling due to amendment decomposition. Soil that has not been properly firmed in the hole can also lead to plant settling and stems can drop below grade leading to crown rot.

Nonetheless, on the basis of recommendations made in many countries there could be some value in these planting practices, especially in the light of the effect organic matter has on avocado root rot. Numerous studies have shown organic matter suppresses the causal agent of root rot. This study evaluated the effect of hole size and amendments on avocado growth in an ideal environment with excellent soil conditions and in a more harsh one with heavy soil texture and the presence of the root rot pathogen.

Materials and methods

On the north island of New Zealand in the Bay of Plenty, 20 trees each were planted to one of four treatments: a) small holes (12 by 18 inches) without amendment; b) small holes with 25% by volume compost; c) big holes (60 deep by 30 wide by 24 wide inches) without amendment and d) big holes with 25% by volume compost. Big holes were dug with a backhoe, while small holes were dug by shovel. Trees were approximately 2 feet tall at planting. Soil was a deep sandy loam at both sites. Trees were irrigated by drip irrigation. Trees were ‘Hass’ on ‘Zutano’ seedling rootstock. Trees were planted the second week of spring 2000. Tree height, trunk caliper and canopy volume were measured on a monthly basis for eight months and then twice a year for the next year. In Carpinteria, California a similar trial was established using ‘Hass’ on ‘Toro Canyon’ rootstock. Trees were approximately 2 feet tall at planting. The grove had a heavy clay loam soil and a history of root rot. The trees were on drip irrigation. The trees were planted summer 2001 and monitored for 18 months after planting.

Results and discussion

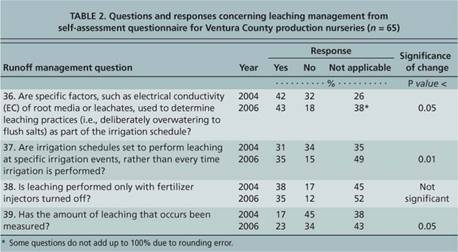

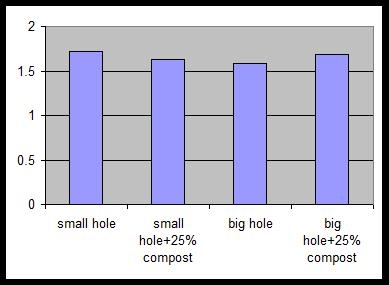

Figures 1and 2 show the results of the different planting treatments at sites in New Zealand on ideal soils and on the heavy soil infected with root rot in California. Only tree height is shown; trunk girth and canopy volume followed similar patterns. From planting onwards, there were no differences in tree growth in any of the treatments at any of the sites. This would lead one to the conclusion that there is no value in and a great expense in making big holes and incorporating amendment. This is especially so in hillside situations where moving equipment and amendments on steep slopes would be very difficult.

The trees at the Carpinteria site, although infested with root rot, all looked good. The addition of organic matter in conjunction with the clonal rootstocks did not apparently provide any greater disease resistance. This is in accordance with work done by John Menge which shows that the greatest benefit derived from mulching are seedling rootstocks. The effect of mulch on disease suppression diminishes with the rootstock’s resistance to root rot.

Figure 1. Tree height (meters) at site 1 in New Zealand 20 months after planting. No differences were found at the 5% level of significance.

Figure 2. Tree height (meters) in California 18 months after planting. No differences were found at the 5% level of significance.

- Written by: Craig Kallsen

University of California (UC) researchers and private industry consultants have invested much effort in correlating optimal citrus tree growth, fruit quality and yield to concentrations of necessary plant nutrients in citrus (especially orange) leaf tissue. The grower can remove much of the guesswork of fertilization by adhering to UC recommendations of critical levels of nutrients in the tissues of appropriately sampled leaves. Optimal values for elements important in plant nutrition are presented on a dry-weight basis in Table 1. Adding them in appropriate rates by broadcasting to the soil, fertigating through the irrigation system or spraying them foliarly may correct concentrations of nutrients in the deficient or low range. Compared to the cost of fertilizers, and the loss of fruit yield and quality that can occur as a result of nutrient deficiencies or excesses, leaf tissue analysis is a bargain. At a minimum, the grower should monitor the nitrogen status of the grove through tissue sampling on an annual basis.

Leaves of the spring flush are sampled during the time period from about August 15 through October 15. Pick healthy, undamaged leaves that are 4-6 months old on non-fruiting branches. Select leaves that reflect the average size leaf for the spring flush and do not pick the terminal leaf of a branch. Typically 75 to 100 leaves from a uniform 20- acre block of citrus are sufficient for testing. Generally, the sampler will walk diagonally across the area to be sampled, and randomly pick leaves, one per tree. Leaves should be taken so that the final sample includes roughly the same number of leaves from each of the four quadrants of the tree canopy. Values in Table 1 will not reflect the nutritional status of the orchard if these sampling guidelines are not followed. Typically, citrus is able to store considerable quantities of nutrients in the tree. Sampling leaves from trees more frequently than once a year in the fall is usually unnecessary. A single annual sample in the fall provides ample time for detecting and correcting developing deficiencies.

Table 1. Mineral nutrition standards for leaves from mature orange trees based on dry-weight concentration of elements in 4 to 7 month old spring flush leaves from non-fruiting branch terminals.

|

element |

unit |

deficiency |

low |

optimum |

high |

excess |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

% |

2.2 |

2.2-2.4 |

2.5-2.7 |

2.7-2.8 |

3.0 |

|

P |

% |

0.9 |

0.9-0.11 |

0.12-0.16 |

0.17-0.29 |

0.3 |

|

K (Calif.*) |

% |

0.40 |

0.40-0.69 |

0.70-1.09 |

1.1-2.0 |

2.3 |

|

K (Florida*) |

% |

0.7 |

0.7-1.1 |

1.2-1.7 |

1.8-2.3 |

2.4 |

|

Ca |

% |

1.5 |

1.6-2.9 |

3.0-5.5 |

5.6-6.9 |

7.0 |

|

Mg |

% |

0.16 |

0.16-0.25 |

0.26-0.6 |

0.7-1.1 |

1.2 |

|

S |

% |

0.14 |

0.14-0.19 |

0.2-0.3 |

0.4-0.5 |

0.6 |

|

Cl |

% |

? |

? |

<0.03 |

0.4-0.6 |

0.7 |

|

Na |

% |

? |

? |

<0.16 |

0.17-0.24 |

0.25 |

|

B |

ppm |

21 |

21-30 |

31-100 |

101.260 |

260 |

|

Fe |

ppm |

36 |

36-59 |

60-120 |

130-200 |

250? |

|

Mn |

ppm |

16 |

16-24 |

25-200 |

300-500? |

1000 |

|

Zn |

ppm |

16 |

16-24 |

25-100 |

110-200 |

300 |

|

Cu |

ppm |

3.6 |

3.6-4.9 |

5 - 16 |

17-22? |

22 |

*California and Florida recommendations for K are sufficiently different that they are presented separately. The California standards are based on production of table navels and Valencias, and those for Florida were developed primarily for juice oranges like Valencia.

The sampled leaves should be placed in a paper bag, and protected from excessive heat (like in a hot trunk or cab) during the day. If possible, find a laboratory that will wash the leaves as part of their procedure instead of requiring the sampler to do this. Leaf samples can be held in the refrigerator (not the freezer) overnight. Leaves should be taken to the lab for washing and analysis as quickly as is feasible.

Often separate samples are taken within a block if areas exist that appear to have special nutrient problems. The temptation encountered in sampling areas with weak trees is to take the worst looking, most severely chlorotic or necrotic leaves on the tree. Selecting this type of leaf may be counter-productive in that the tree may have already reabsorbed most of the nutrients from these leaves before they were sampled. A leaf-tissue analysis based on leaves like this often results in a report of general starvation, and the true cause of the tree decline if the result of a single nutritional deficiency may not be obvious. Often in weak areas, it is beneficial to sample normal appearing or slightly affected leaves. If the problem is a deficiency, the nutrient will, generally, be deficient in the healthy-looking tissue as well.

Groves of early navels that are not normally treated with copper and lime as a fungicide should include an analysis for copper. Copper deficiency is a real possibility on trees growing in sandy, organic, or calcareous soils. For later harvested varieties, leaves should be sampled before fall fungicidal or nutritional sprays are applied because nutrients adhering to the exterior of leaves will give an inaccurate picture of the actual nutritional status of the tree.

Usually leaf samples taken from trees deficient in nitrogen will overestimate the true quantity of nitrogen storage in the trees. Trees deficient in nitrogen typically rob nitrogen from older leaves to use in the production of new leaves. Frequently, by the time fall leaf samples are collected in nitrogen deficient groves, these spent spring flush leaves have already fallen. Nitrogen deficient trees typically have thin-looking canopies as a result of this physiological response. Since the spring flush leaves are no longer present on the tree in the fall when leaves are sampled, younger leaves are often taken by mistake for analysis. These leaves are higher in nitrogen than the now missing spring flush leaves would have been and provide an inaccurately higher nitrogen status in the grove than actually exists.

Critical levels for leaf-nitrogen for some varieties of citrus, like the grapefruits, pummelos, pummelo x grapefruit hybrids and the mandarins, have not been investigated as well as those for oranges. However, the mineral nutrient requirements of most citrus varieties are probably similar to those for sweet oranges presented in Table 1, except for lemons, where the recommended nitrogen dry-weight percentage is in the range of 2.2- 2.4%.

A complete soil sample in conjunction with the leaf sample can provide valuable information on the native fertility of the soil with respect to some mineral nutrients and information on how best to amend the soil if necessary to improve uptake of fertilizers and improve water infiltration.

- Posted By: Chris M. Webb

- Written by: W. Thomas Lanini

In recent years, several organic herbicide products have appeared on the market. These include Weed Pharm (20% ace c acid), C Cide (5% citric acid), GreenMatch (55% d limonene), Matratec (50% clove oil), WeedZap (45% clove oil + 45% cinnamon oil), and GreenMatch EX (50% lemongrass oil), among others. These products are all contact type herbicides and will damage any green vegeta on they contact, though they are safe as directed sprays against woody stems and trunks. These herbicides kill weeds that have emerged, but have no residual activity on those emerging subsequently. Additionally, these herbicides can burn back the tops of perennial weeds, but perennial weeds recover quickly.

These products are effective in controlling weeds when the weeds are small and the environmental conditions are op mum. In a recent study, we found that weeds in the cotyledon or first true leaf stage were much easier to control than older weeds (Tables 1 and 2). Broadleaf weeds were also found to be easier to control than grasses, possibly due to the location of the growing point (at or below the soil surface for grasses), or the orientation of the leaves (horizontal for most broadleaf weeds) (Tables 1 and 2).

Organic herbicides only kill contacted tissue; thus, good coverage is essential. In test comparing various spray volumes and product concentrations, we found that high concentrations at low spray volumes (20% concentration in 35 gallons per acre) were less effective than lower concentrations at high spray volumes (10% concentration in 70 gallons per acre). Applying these materials through a green sprayer (only living plants are treated), can reduce the amount of material and the overall cost (http://www.ntechindustries.com/weedseeker-home.html). Adding an organically acceptable adjuvant has resulted in improved control. Among the organic adjuvants tested thus far, Natural wet, Nu Film P, Nu Film 17, and Silwet ECO spreader have performed the best. The Silwet ECO spreader is an organic silicone adjuvant which works very well on most broadleaf weeds, but tends to roll o of grass weeds. The Natural wet, Nu Film 17 and Nu Film P work well for both broad leaf and grass weeds. Although the recommended rates of these adjuvants is 0.25 % v/v, we have found that increasing the adjuvant concentration up to 1% v/v o en leads to improved weed control, possibly due to better coverage. Work continues in this area, as manufacturers continue to develop more organic adjuvants. Because organic herbicides lack residual activity, repeat applications will be needed to control new flushes of weeds.

Temperature and sunlight have both been suggested as factors affecting organic herbicide efficacy. In several field studies, we have observed that organic herbicides work better when temperatures are above 75F. Weed Pharm (acetic acid) is the exception, working well at temperatures as low as 55F. Sunlight has also been suggested as an important factor for effective weed control. Anecdotal reports indicate that control is better in full sunlight. However, in a greenhouse test using shade cloth to block 70% of the light, it was found that weed control with WeedZap improved in shaded conditions (Table 3). The greenhouse temperature was around 80F. It may be that under warm temperatures, sunlight is less of a factor.

Organic herbicides are expensive at this time and may not be affordable for commercial crop producti on. Because these materials lack residual activity, repeat applications will be needed to control perennial weeds or new flushes of weed seedlings. Finally, approval by one's organic certifier should also be checked in advance as use of such alternative herbicides is not cleared by all agencies.

Review tables below...

(Table 1. Broadleaf (pigweed and black nightshade) weed control (% control at 15 days a er treatment), when treated 12, 19, or 26 days after emergence.

|

Weed |

age |

||

|

|

12 Days old |

19 days old |

26 days old |

|

GreenMatch Ex 15% |

89 |

11 |

0 |

|

GreenMatch 15% |

83 |

96 |

17 |

|

Matran 15% |

88 |

28 |

0 |

|

Ace c acid 20% |

61 |

11 |

17 |

|

WeedZap 10% |

100 |

33 |

38 |

|

Untreated |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 2. Grass (Barnyardgrass and crabgrass) weed control (% control at 15 days after treatment), when treated 12, 19, or 26 days after emergence.

|

Weed |

age |

||

|

|

12 Days old |

19 days old |

26 days old |

|

GreenMatch Ex 15% |

25 |

19 |

8 |

|

GreenMatch 15% |

42 |

42 |

0 |

|

Matran 15% |

25 |

17 |

0 |

|

Ace c acid 20% |

25 |

0 |

0 |

|

WeedZap 10% |

0 |

11 |

0 |

|

Untreated |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Table 3. Weed control with WeedZap (10% v/v) in relation to adjuvant, spray volumne and light levels. Plants grown in the greenhouse in either open conditions or under shade cloth, which reduced light by 70%. |

|

||||

|

Pigweed control (%) |

Mustard control (%) |

|

|||

|

|

Sun |

Shade |

Sun |

Shade |

|

|

WeedZap + 0.1%v/v Eco Silwet (10 gpa) |

31.7 |

93.3 |

26.7 |

35.0 |

|

|

WeedZap + 0.5%v/v Eco Silwet (10 gpa) |

31.7 |

48.3 |

43.3 |

71.7 |

|

|

WeedZap + 0.5%v/v Natural Wet (70 gpa) |

26.7 |

94.7 |

26.7 |

30.0 |

|

|

Untreated |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

LSD.05* |

5.7 |

11.5 |

|

|

|

* Values for comparing any two means. Pigweed and mustard were each analyzed separately.

- Written by: Jim Downer

Horticulture is the cultivation of plants as ornamentals or for the production of food. When things go wrong (plants grow poorly or not at all), horticulturists sometimes turn to products that can “cure”, revitalize, invigorate, stimulate or enhance the growth of their plant or crop. A horticultural consultant colleague of mine, has often told me, “There are no miracles!” Unfortunately, when nothing else has worked, many people will turn to so called miracle products in hopes of a cure. Products that purport to give you that miracle are termed snake oil. Snake oil products claim many things, but usually without referenced research reports from Universities. Snake oil products almost always offer numerous testimonials to support their use. Those who provide testimonials are usually not researchers. Professional horticulturists, farmers and gardeners should be able to recognize snake oil products and avoid their use—we should base our horticultural decisions on sound research based information, not on marketing claims and testimonial based admonitions.

Science Based

The most creative and effectively marketed snake oil products often cite sound biological facts or knowledge and then attempt to link their product to this knowledge, but references to the published research about their product are always missing. Very often, snake oil products will use jargon relating to the chemistry, biology or microbiology of their products in an attempt to impress potential users with terms that sound informative but are used in a meaningless context. In some cases, these products are “ambulance chasers” and follow the most recent pest outbreak or natural disaster in an attempt to make money from desperate clients.

Works on a new principle

A prime indicator of snake oil products are that they rely on a new principle that gives them their efficacy. This “new” principle may be entirely fabricated by the manufacturer or have a shred of truth based in current science, but the science is so distorted that there is no truth in the claim. Very often the active ingredient is not listed on the label and is a “secret” or proprietary substance. A clear explanation of the scientific principle, its discoverer, where it was published and how it relates to the product at hand is rarely or never available.

Research Based

Some products make claims of efficacy based on extensive research. But who did the research? Upon inspection, we find that independent, third party research, published in a peer reviewed journal is lacking. In house research or research conducted by contract with other companies may not have the same degree of objectivity as University based research projects. Some products allude to University research but never tell the user that the research found that their product was not effective. Sometimes product literature tells outright lies about the efficacy of the product discussed in the research.

Sometimes a retired researcher will start selling a product based on the good research they have done in the past, but with little bearing on the efficacy of the current product or material. Past affiliations with Universities are no guarantee that products developed after the researcher has left the institution are efficacious. Only current, published reports of efficacy in peer reviewed journals are acceptable references.

Snake oil products can sometimes be lawbreakers!

Products that purport to control a pest such as a disease organism or an insect or weed, but are not registered with the State or Federal EPA and do not have pesticide registration numbers, are not pesticides and can not be used for that purpose. It is a violation of state and federal laws to apply products as pesticides when they are not labeled for that use. Sometimes a product claims to boost plant health and thus avoid diseases, also avoiding the pesticide registration process. Health boosters, activators, and stimulators are not considered pesticides by regulatory agencies; however, they are often not efficacious or supported by University research findings.

It is too good to be true

Some problems like Armillaria (which causes root rot and basal cankers of many ornamental and orchard trees) are essentially incurable. All the traditional sources of information suggest ways to limit the disease but no “cure” is offered. Along comes a product that kills the pathogen and reinvigorates the sick host. Sounds too good to be true? Then the product is probably snake oil. Rarely do efficacious pest management practices or products come to market without some kind of University based research. Again, there are no miracles.

Soil Microbiology Products and Services

All plants have root systems and almost all are rooting in soil, and since we do not see their roots very well, there is a lot of snake oil that concerns soils and soil treatments. Polymers, growth activators, hormones, vitamins, fertilizers, worm castings, composts and their teas, are but a few products that may fall into this category. Since none of these products claim to be a pesticide, the careful efficacy testing required for state or federal registrations is not required. Efficacy claims can run to the extreme.

Mycorrhizal Fungi

Some of the most convincing products are those that have solid scientific basis for efficacy but no direct evidence that they work. A classical example is fungal mycorrhizae forming inoculants for landscape trees. Mycorrhizae are not snake oil. However, some products that purport all the things that mycorrhizae can and do achieve for plants may be. Many of the numerous scientific papers written on mycorrhizal fungi do not indicate that mycorrhizae are necessarily lacking from most soils, or that the products used to add them to soil are viable. In a study of ten commercial mycorrhizae products, Corkidi et al.(2004), found that four of the ten failed to infect the bioassay plants and in a second trial, three of the ten products failed to infect.

Biological control

A considerable amount of time is spent each year by companies producing biological control microorganisms. Although these often show good efficacy in university based laboratory or greenhouse trials, and this research is published, there are few products that show efficacy in field-based trials. Many of the Trichoderma based products simply do not work when applied as products outside the lab or greenhouse. Biological control of soilborne diseases is an elusive thing that we seek to understand constantly, catch glimpses of in the field, study intensively and consistently fail to recreate when and where we want it to happen. Rarely has a single organism been applied with disease control effect in field settings. Soil ecosystem level changes (like massive mulch applications) can promote biological control of root rot diseases, but these effects are caused by many kinds of fungi that are naturally occurring in the environment.

Soil Food Webs

Manipulation of Soil Food Webs is purported to balance all the complexities of soil so that plants will grow well. The concept is to balance the various microorganisms so that the soil will benefit the crop at hand. Lab services are used to diagnose the organism content of a given soil sample. Horticulturists then use this information to make the recommended changes to modify the soil ecology and enhance plant performance. A “healthy soil” will grow healthy plants; a “sick soil” is unproductive. The theory predicts that in poorly managed soils, all the “good” fungi are killed and only the plant pathogens remain. The data relating good fungi to bad and how their populations interact is rarely given and published references with this information are lacking. Detailed information on the interactions of soil food webs with specific plant pathogenic fungi are distinctly lacking in the literature.

Soil food webs are complex. Ferris and others have found that nematodes are good indicators of the status of the soil food web. Since nematodes feed on fungi and bacteria, the two most important manipulators of organic carbon, nematode guilds can be monitored to determine the various successional stages of decomposers in a food web. Maintenance of labile sources of soil organic carbon ensures adequate levels of enrichment for opportunist bacterivore nematodes and thus adequate fertility necessary for crop growth. Labile organic carbon can be supplied by organic amendments or by the roots left behind after a crop is harvested. Organisms come and go in the soil, dependent on carbon available for their growth. If one group (guild) of bacteria or fungi use up the available food, another will take over on what is left. Ferris and others refer to the changes in food web function as functional succession. Analysis of nematode fauna has emerged as a bioindicator of soil condition and of functional and structural makeup of the soil food web. Nematodes are used to assess the food web because evaluation of the food web structure is in itself very difficult; you would have to inventory and assess all of the participants. Functional analysis of the web is difficult because it may not indicate how the various functions are being accomplished or whether they are sustainable. Merely counting bacteria and fungi gives nothing but a snapshot view of what was happening the day the samples were obtained. Since nematodes are the most abundant animal in soils, they can be used as a tool in assessing the structure, function and resilience of the soil food web.This understanding of the biology of soils is new and not yet practicably applicable on a wide basis.

Compost Teas

A natural extension of food web science is the use of compost teas to “strengthen” the food web. Compost teas are “brewed” from compost usually in an aerobic fermenter. They may be aerated or non-aearated. Because the feedstock (compost) is highly variable, the resultant teas can also be quite different. Due to the tremendous number of variables in “brewing” compost teas (ph, fermentation time, water source and content, temperature, added nutrients, feedstocks and aerated vs. not) the results are hard to replicate and quite variable; this makes studies hard to publish. Compost teas contain many different substances plus nutrients that plants can use for growth or that can act as plant growth stimulators. The problem comes with rates. How much do you apply and how often? There is a lot of experimentation going on by the users of the teas but not much validation in the academic community (especially research on trees) due to the variability of these systems.

Horticultural Myths

These are practices and or products that many people working in our industry may hold to be useful but have no scientific basis for their method of action. They are formed from misinformation passed on over the generations or from common observations that are misinterpreted. A good example is that of placing gravel or rocks in the bottom of a planting hole to increase drainage for the rootball. This is borne out by the fact that these drawings exist in old books. Even though the mistakes are corrected in modern texts the myth that rocks in the bottom of a planting hole creates drainage, lives on today, and actually shows up in some modern landscape architectural specifications.

Another myth is the notion that pruning woody plants stimulates their growth. The more severe the pruning, the more the plant is shocked into good growth. Although the growth of latent buds from major limbs that have been headed back leads to copious regrowth, if you compare the overall growth of this tree to a similar unpruned tree, the pruned tree will have grown less on the main trunk over the same amount of time. Transplanted trees do not need to be pruned to compensate for their root loss. Sometimes when trees are moved, compensatory pruning is done to “balance” the roots with the shoots. Research has consistently shown that as mentioned above, pruning is a growth retarding process, and thus slows the establishment of transplanted trees.

There are many funny ideas about mulches. Almost any mulch can be applied to the soil surface with few bad affects. There are some exceptions where the mulch contains toxic acids or contains weed seeds. However, the belief that high C:N ratio mulches (contain a lot of wood) will extract nitrogen from under the soils to which they are applied has little or no scientific evidence to support it. Just the opposite is true. Over time, woody mulches decay and release nitrogen to underlying root systems.

A product that has attained Horticultural Urban Legend status is Vitamin B1. In the 1930's, Caltech's James Bonner discovered, that Thiamin (vitamin B1) was able to restore growth to pea root tips that had languished in tissue culture. It was concluded to be essential in plant growth media. Bonner later found that B1 had little growth promoting effects on most whole plants in hydroponic culture, but that some plants such as camellia, and cosmos showed dramatic growth increased to added B1 vitamins. Bonner latter discovered that thiamin production was associated with the foliage of growing plants. The hoax was on in 1939 when Better Homes and Gardens magazine ran an article that claimed thiamin would produce five inch rose buds, daffodils bigger than a salad plate and snapdragons six feet tall! In1940, Bonner entered into collaborative research with Merck pharmaceutical company to master the growth promoting effects of B1, account for the wide variability in his experimental results and develop a product that gave consistent good results. Bonner proved during this period that B1 was phloem mobile was made in leaves and transported downward in stems. Bonner's experiments with Cosmos continued, but with varying results, so he sought cooperative research with University experiment stations around the country. Results were mixed, some showed growth promotion, most not. By 1940,other physiologists widely reported negative results. By1942 Bonner was debunking his own discoveries, stating that the effect only ever occurred in very few plants and that since thiamin was found in soil itself, field applications were unlikely to benefit plants. Bonner ultimately fully retracted his claims of efficacy by saying “It is now certain, however, that additions of vitamin B1 to intact growing plants have no significant or useful place in horticultural or agricultural practice”. The public craze and fanatical headlines about thiamin continued but Merck withdrew all interest and funding in the concept so as to distance itself from a product that does not work.

Conclusions

New products come and go. Snake oil products often disappear rapidly, when their efficacy fails to materialize after application. Products that confound their purported results with fertilizers or growth stimulators can persist, but eventually they too fail to live up to expectations at some point and will fade from popularity. Try to obtain some kind of consensus with university based research or other peer reviewed research reports, field efficacy trials that you run for yourself, and not on the testimonials of others. If you decide to conduct your own trials, they must be replicated and statistically analyzable, otherwise they are little more than anecdotal observations that have little value in quantifying the effects of the above mentioned products and practices. For more help with trials, seek out University Extension agents and specialists. This is their job, and they are willing partners in field research. After awhile, you will be able to ascertain the nature of the “oil” before you purchase it.