- Author: Ben Faber

Replanting Trees in Mature Citrus Groves

By Craig Kallsen, UC Cooperative Extension Advisor, Kern County

While citrus groves are long-lived, the individual trees that compose the grove are not necessarily so. Inevitably, for many reasons, some mature trees will eventually die and be replaced with baby trees from the nursery. The process of growing these replants into productive trees can be a slow process and frequently hazardous to the health of the replant.

When considering replanting dead or dying trees, the first relevant decision, and generally outside the scope of this article, is the economic viability of the grove. If many replants are required, perhaps the soil or location is unsuitable for citrus. It may well make more economic sense to push the grove out and switch to a different crop.

Before replanting a given tree, the grower should try to determine why the original tree or trees died. If it was a stubborn-infected tree, neighboring host weeds, if present, such as the mustards or Russian thistle, may require control. If the original tree died from a root rot, the irrigation system may need replacement and water application efficiency or drainage may need to be addressed. Vertebrate pests, insect pests, fungal diseases or nematodes may need to be treated. A wide variety of rootstocks are available to the grower, and changing the rootstock of the replants from what currently exists in the field might be a viable option for improving the health and productivity of the new trees in response to disease, incompatibility issues, frost hazard or pH related nutrient-absorption problems in the grove.

After deciding to replant missing or sick trees, select the best possible replants from the nursery. Equal, if not more, care should occur in selecting replants as occurred in buying the original trees for the orchard. There is a tendency for “left-over” trees to end up as replants. Trees should be large, but not root bound or J-rooted, vigorous, with healthy, green foliation and free from insect, mite and snail pests.

An unexpected hurdle in some older orchards is choosing the variety to replant. Citrus is long-lived tree and the navel orange is a good case in point. For example, some navel varieties planted decades ago are no longer available. Some groves have changed hands so many times growers are not sure what selection of navel they have in their grove. In fact, navels were being planted so fast in the 1960's that it's doubtful that even the original owners were sure which rootstock or variety they were getting. Replacing a Frost Nucellar with a Parent Washington is of little consequence; however, real differences in maturity become apparent between a Newhall versus Washington navel. When many blocks of citrus are replanted at the same time, special care should be taken to insure that the Valencia replants end up in the Valencia groves and not in the navel groves and vice versa. Putting different varieties on the same trailer for planting is asking for a mix-up.

The environment for the replant in a mature grove is very different from that which young trees in a newly planted grove experience. The growth rate of the replant will be slower, simply because of shading from large, full-grown neighbors, and this is tough to mitigate. However, the grower is able to adjust the flow of water, nutrients and pesticides to the size of the replants compared to the mature trees. The water requirement of the newly replanted tree is probably 1/50th of that of the mature tree (i.e. the newly planted tree may only transpire about one gallon of water per day during the summer). Water to the replant may be decreased by the use of emitters having a much reduced flow-rate (which have to be monitored closely, as the smaller orifices are more likely to plug) or through the use of devices, such as pulsators which interrupt the flow of water at intervals reducing the total flow rate per unit time. If fertilizer or amendments are injected through low-volume irrigation systems, decreasing the flow of water to the trees through smaller emitter orifices will concomitantly decrease the flow of nutrients. Reducing the level of fertilization is critical for good replant growth, since for example, the nitrogen requirement of the young tree is only a fraction of that for the mature tree.

Controlling weeds adjacent to replanted citrus avoids excessive competition for light, nutrients, and water. Weeds can become especially thick around replants because of the more open, less-shaded ground around them as compared to the limited area now adjacent to mature trees. When the herbicide applicator encounters these weedy areas, the tendency is to give the replant space an especially heavy application. On young trees this can be especially damaging as the chance for both foliar and root uptake of the pre-emergent herbicides, and foliar uptake and burn from post-emergent herbicides, increases. In heavily replanted groves, the use of only carefully applied post-emergent herbicides may be beneficial until the replants achieve sufficient size to tolerate the pre-emergent materials. Many groves have sufficient residual pre-emergent herbicides to carry them through a year or so of replant establishment without a substantial increase in weed pressure. The hoe is a surprisingly effective tool for keeping weeds under control around replants and provides an opportunity for scheduled inspection of the replants for other possible problems. Gophers quickly find weedy areas and, experience suggests, consider citrus roots just as appetizing as the roots of weeds.

Some pre-emergent herbicides are registered for new citrus plantings and some may be injected through the irrigation system. Because of their increased cost, growers may be reluctant to use these potentially less-phytotoxic chemicals. The grower should be aware that most label directions for many of the less-expensive pre-emergent, and thus commonly used, herbicides are much different for young trees as opposed to mature trees. For example, pre-emergent herbicides containing simazine and diuron, should not be used on citrus that has been in the ground for less than a year, and some herbicides containing both diuron and bromacil, are not labeled for use if the citrus is less than three years old. The use of these herbicides in mature groves can greatly affect the growth of new replants, especially, if used in groves with coarse soils low in organic matter. Some applicators are cautioned to turn off their machines before spraying some pre-emergent materials adjacent to a replant, but the grower should be aware that some herbicides travel down-slope with surface-drainage water.

Inspection of replants should be an active part of the pest control procedure of any grove. The pests of mature trees are rarely the same as for the juvenile replants. Several species of ants are capable of establishing hives in the wraps of young replants, which can result in trunk girdling. Heavy feeding of the false chinch bug, which does not damage mature citrus, can result in the rapid death of a replant, while pests like the brown garden snail, California orangedog (http://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/r107302311.html) or Fuller rose beetle can set the tree back seriously. Ground squirrels, meadow mice and rabbits can strip the bark and leaves or girdle the trunk killing the replant.

Young trees planted in mature groves appear to be more at risk from freezing than do trees of equal age in new grove establishments. This may be partly due to the increased shading of the ground by large trees and tree litter inside mature groves, which allows for less absorption of heat for radiation back to the trees at night, or the generally, poorer health of replant trees. Replants in cold areas definitely need to have the trunk tree-covered or trunk wrapped with an insulating material. If possible, avoid tying the wrap to the tree as lower wind speeds within a mature grove makes tying less necessary. If not checked, as replants commonly are not, these ties may eventually girdle the tree.

Producing mature, productive trees from replants requires extra effort and expense. To make matters worse, the pay-off can be a number of years down the road. However, actively growing vigorous replants, in older blocks with many missing trees, may eventually determine the difference between profit and loss. Big, healthy replants can help sell an older orchard; an important consideration when owners' thoughts of getting up in the middle of Christmas or New Year's Eve, to start wind machines begins to lose its appeal.

Figure 1. Replants are subject to many vicissitudes. This replant appears to be the victim of crows looking for something to eat in the tree wrap (photo by Craig Kallsen).

- Author: Ben Faber

After the fires, the question has come up of whether an orchard should be replanted or topworked in the field, possibly to a new variety. This has been an issue in the past and was addressed in a little study nearly 20 years ago. The study still bears relevance today and applies to both avocado and citrus. The availability of avocado trees for replanting is in serious short supply, so replanting may not be an option at this point.

There are many changes going on in the citrus industry and one opportunity is the conversion of an orchard to another variety of citrus. If this is a consideration, then the question becomes one of whether the orchard should be topworked or replanted with new nursery trees. If the trees are healthy and under 20 years of age (it is possible to topwork older trees) and the new scion is compatible with the interstock or rootstock, then topworking can come into production sooner than a new replant. If the planting density needs to be changed or serious soil preparation or a new irrigation system needs to be installed, then replanting might be the preferred choice.

The chance to convert is also dependent on the availability of new trees and budwood. New varieties can often be in short supply. It's best to make sure that for either option that the material is there. For topworking, T-budding is more conservative of material than stick grafting. If topworking is chosen, then it must be decided whether to graft the scaffold branches or the stump. Stump grafting makes for a lower tree, but scaffold grafting reduces the risk of losing the topworked tree from damage to the graft from birds, pests, wind or frost.

It is often assumed that topworking is cheaper than replanting, but as the following example shows, it probably is not. In Santa Paula, ‘Olinda' Valencias on ‘Carrizo' rootstock were converted to scions ‘Allen' Eureka lemon, or ‘Powell' late navel. In 1998 and 2000, the ‘Olinda's were interplanted with either ‘Allen' on ‘Macrophylla' or late navel ‘Powell' or ‘Chislett' (on either ‘Carrizo or ‘C-35' rootstocks). The ‘Olinda's were topworked in 2002 and 2003 to one of the new scions. In a few cases, ‘Allen' was stump grafted, but most trees were scaffold grafted.

Several steps are required for topworking that will ensure success. These are listed below:

• Get a reputable person to do the work.

• Time of year is critical for grafting. Spring is best.

• Leave a nurse limb.

• Decide to stump or scaffold graft.

o Stump grafting requires only 3 – 4 buds or sticks

o Scaffold grafting requires 2 buds per scaffold. Consider winds since even one-year old unions are very tender.

• Sequence of events

o Line up budwood

o Remove top of tree and stack brush

o Whitewash trunks

o Paint cutoff surfaces

o Insert grafts

o Wrap grafts with plastic tape

o Place white paper bag over grafts and tape in place

Later

o Keep after ants and snails

o Shred brush

o Remove bags when shoots start growing through them.

o Bi-monthly, in first year, brush out water sprouts. Less often in the next 2 years

Much of this work can be contracted with the grafter, who usually assures some level of performance, something like 90% take. It is up to the grower to ensure that pests do not take out the grafts.

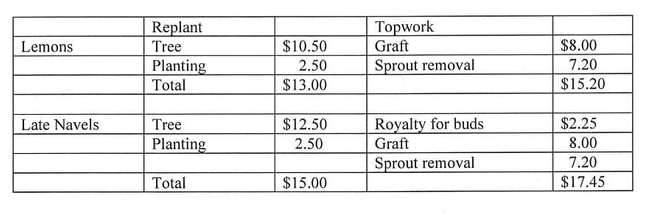

The costs of topworking are associated with the costs of the budwood (as much as $3 per tree), the act of grafting (depending on stump or scaffold, $8-10 per tree) and water sprout removal. Sprout removal is six times in year one, eight times in year two and only four times in year three. At a labor rate of $12 per hour, sprout removal costs $7.20 per tree.

A like for like comparison of topworking versus replanting based on 2002 data is shown below.

So in the case of both the lemon and navels it costs a bit more to topwork, but the results are earlier production. Here the topworked trees gain the economic advantage. For example, if cultural costs were $1000 per acre per year (20 by 20 ft. spacing) and, conservatively, two years are saved, the maintenance savings per tree would be $18. In the above study the time advantage appears even greater. Three-year old topworked lemons produce about the same as 6-year old replants. Two year old topworked navels have a significantly larger canopy than six-year old replant navels and appear to have about the same fruit set for the coming year.

- Author: Ben Faber

We are creatures of habit and when we see the effects of a treatment, we can often persist in seeing the same or similar symptoms and assuming the cause is the same. In a recent case, a newly planted ‘Pixie' orchard, planted in August had gone into an old ‘Valencia' ground. The trees went through an adjustment period, but still didn't look sprightly in the fall. The grower applied a hand application of urea on the rootball that within 10 days had caused the trees to go into a salt swoon. Meaning, they got too much fertilizer that burned them. The grower seeing the effect, immediately started the sprinklers, but the damage was done. Several months later the trees had either died or were still lingering, but hanging in there. The trees were still coming out of winter, but the trees hadn't perked up. It was a dry winter and some of the yellowing was due to underirrigation, that overall yellowing from lack of nitrogen and the leaves were curled. But the assumption was still that the trees were recovering from the salt burn from the urea.

Looking more closely at the trees, something else was odd about some of the trees that were continuing to die. The leaves suddenly wilted. Getting down on hands and knees and digging around the roots, there were few roots and ………………………….a tunnel. A gopher had been at this tree and the lack of roots were probably due to Phytophthora root rot. Looking around there were some old ‘Valencias' that had been hit by gophers and there were gophers mounds and runs all over the place.

So, young trees planted in the heat of the summer into root rot ground with gophers waiting in anticipation that had been salt burned in a year with little rainfall. A lot of causes for trees that generally weren't happy – triste, as they say in French.

So what are the lessons here? Avoid old citrus ground when planting with citrus, and if you can't make sure, don't plant in a stressful period. Phytophthora loves stressed trees and adding lack of rainfall an gophers and salt, just heightens the stress. Make sure to get the irrigation right. Don't irrigate them to the schedule of the older trees and start them off on one of the phosphite materials.

Images

Wilted, yellow leaves from lack of water and Phytophthora

Gopher chewing on stem

Gopher run and lack of roots from Phytopthora and gopher

Gopher mounds in planting area

Older Valencias dead and dying from Phytophthora and gophers