An interesting article published by the Migration Policy Institute examines the racialization of those who make up the “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin” category on census forms.

Written by UC Irvine sociologist Rubén Rumbaut, a veteran chronicler of the immigrant experience, the piece delves into the history of racial and ethnic classifications, and on the impact that what began as an administrative move to classify people of Latin American ancestry has had on how they now define themselves in terms of race.

Are Hispanics a “race” or, more precisely, a racialized category? In fact, are they even a “they?” Is there a Latino or Hispanic ethnic group, cohesive and self-conscious, sharing a sense of peoplehood in the same way that there is an African American people in the United States? Or is it mainly administrative shorthand devised for statistical purposes; a one-size-fits-all label that subsumes diverse peoples and identities?

The article details the history of “Hispanic” census self-identification, which dates to the late 1960s. A Spanish-origin identification category was added to the 1970 census long-form questionnaire, first tested in the November 1969 Current Population Survey. From the start the results were uneven, with disparity between who identified as “Hispanic” and those with a Spanish surname:

For example, in the Southwest, only 74 percent of those who identified themselves as Hispanic had Spanish surnames, while 81 percent of those with Spanish surnames identified themselves as Hispanic. In the rest of the country, 61 percent of those who self-identified as Hispanic had Spanish surnames, and a mere 46 percent of those with Spanish surnames self-identified as Hispanic.

Rumbaut points out that “prior to 1970 Mexicans were almost always coded as white for census purposes, and were deemed white by law (if not by custom) since the 19th century.” This has changed in the decades since the “Hispanic” category was introduced, with Mexicans and other Latinos frequently identifying as non-white.

Currently, census respondents are asked to choose whether or not they are of “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin.” This is an ethnic identification, not a racial one; they then go on to identify their race, which does not include Hispanic or Latino. Rumbaut writes:

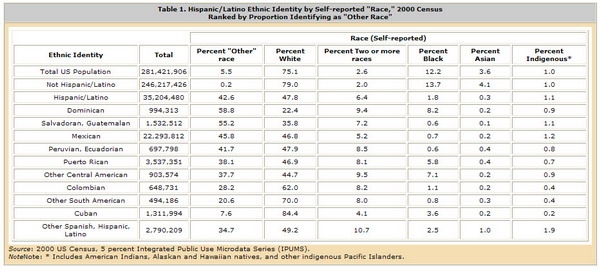

Overall, only half of the 35.2 million Hispanics counted by the 2000 census reported their race as white (48 percent), black (1.8 percent), or Asian (0.3 percent). In contrast, 97 percent of the 246.2 million non-Hispanics counted reported their race either as white (79 percent), black (14 percent), or Asian (4 percent).

Most notably, there was a huge difference in the proportion of these two populations that chose “other race.” While scarcely any non-Hispanics (0.2 percent) reported being of some other race, among Hispanics that figure was 43 percent — a reflection of more than four centuries of mixed European and Native American heritage in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as differing histories and conceptions of what race means.

For example, in 2000, 40 percent of the Mexican-origin population in California reported as “white,” while 53 percent reported as “other race.” In Texas, 60 percent of the same population reported as “white,” while only 36 percent reported as “other race.”

Salvadorans and Guatemalans were also more likely to consider themselves “white” in Texas and “other” in California. The same went for Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Dominicans and Colombians in Florida, who were far more likely to consider themselves “white” than their peers in New York and New Jersey.

Rumbaut concludes:

This is a label developed and legitimized by the state, diffused in daily and institutional practice, and finally internalized — and racialized — as a prominent part of the American mosaic.

That this outcome is, at least in part, a self-fulfilling prophecy, does not make it any less real. But the reliance on “Hispanic” or “Latino” as a catch-all category is misleading, concealing the multiple origins and the uncertain destinies of the peoples so labeled.

Source: Southern California Public Radio, Leslie Berestein Rojas, “Creating race: How the ‘Hispanic or Latino’ category came to be,” May 3, 2011.