Posts Tagged: berries

It looks great, but does it taste great?

Taking a look at melons, berries, tomatoes, pears, stone fruit, and more, researchers from UC Davis, along with collaborators from the University of Florida, are focusing on increasing consumption of specialty crops by enhancing quality and safety. Funded by the USDA, work on this Specialty Crops Research Initiative (SCRI) grant began about a year ago.

Americans, after years of hearing that fresh produce is valuable for numerous health benefits, have still not significantly increased their consumption. So, why don’t we eat more fruits and vegetables? Researchers believe that the key reason is that the quality of produce is inconsistent – often with poor texture, flavor or aroma. It might look beautiful on the outside, but when you take a bite – Ugh! It just doesn’t match up to its attractive exterior.

Most produce found at the local market is harvested from the field or orchard before it is fully ripe, shipped a long distance, and then the ripening is completed at a regional produce distribution center or at the local market.

“Harvesting produce early reduces losses due to bruises, decay and other defects,” explained Beth Mitcham, SCRI Grant UCD project leader, “but oftentimes the product never reaches its potential, a full ripe flavor or aroma. Fresh produce, especially when harvested near full ripe stage, can be challenging to handle properly.”

The SCRI grant is an ambitious effort to understand what characteristics are critical for consumers to enjoy produce and develop better methods to measure flavor quality, then work with better tasting varietals and improved shipping and handling practices to allow economically viable delivery of truly delicious fruits and vegetables.

Consumer focus groups are being interviewed for their input, trained taste panels are enjoying a variety fresh produce, and experiments with pallet shrouds and other modified atmosphere transportation experiments are underway. Significant information has already been elicited from consumer groups. Through focus groups, the investigators have discovered that aroma and texture are nearly as important as sweetness, and shoppers get really irritated when produce looks good but tastes bad, and this keeps repeat purchases to a minimum.

Produce managers also have a tough time: set up displays of produce, keep it at the right temperature, watch people wandering around squeezing everything to see if their firmness requirements are met, meanwhile damaging the fruit. It’s a tough market for fresh fruit these days, with fewer consumers’ dollars allocated for produce purchases, but with the advances researchers are making through the SCRI project and others, sweet success is on the way.

Note: This topic was featured on a CBS13 (KOVR) News clip dated 7/17/10, see: http://www.cbs13.com/video/?id=76639@kovr.dayport.com

Winegrapes ripen, unless berry shrivel strikes

August visitors to California wine country can see winegrapes ripening – green changing to gold, red and purple. This is the critical final stage of development, and its success drives one of the state's economic engines, with wine sales generating $18 billion in revenue in 2009. Wine country is also a tourist magnet and a job generator; the industry has a $61.5 billion economic impact statewide each year.

If this is a typical year, California will produce 90 percent of the nation’s wine. In normal vines, the ripening period means sugars and pH increase, while acids (primarily malic) decrease. Other compounds such as tannins develop, and all these factors contribute to the flavors and aromas in the wine that eventually results. (See healthy Cabernet Sauvignon, at right.)

However, in recent years growers have become increasingly concerned about a malady that appears during this phase. Known as “berry shrivel,” this disorder leads to shriveling of berries on a cluster.

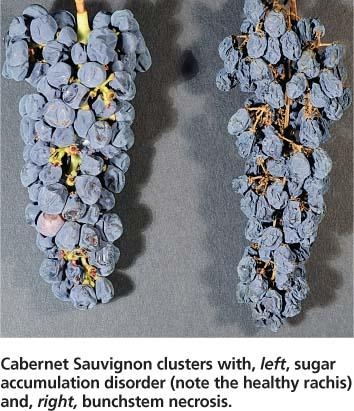

There are several kinds of berry shrivel. Of greatest concern to growers and winemakers are sugar accumulation disorder (SAD), in which grapes turn flabby and lack sugar, and bunchstem necrosis, (BSN) in which grapes turn raisin-like on the vine, losing juice and often developing undesirably high sugar content. (See California Agriculture) Either of these disorders makes the fruit less desirable for winemaking, with yield and production losses.

Berry shrivel afflicts both red and white varieties. Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot are the major red varieties to be affected so far. Among the white varieties, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Semillon and Riesling have shown symptoms.

The malady usually becomes apparent when winemakers or sugar samplers are in the vineyard tasting fruit. Once detected, vintners will often make a pass through the vineyard just ahead of the harvest crew to drop this fruit due to its low sugar content and off-flavored juice.

"Berry shrivel usually affects a small proportion of a vineyard's fruit – perhaps 5 percent -- but in particular vineyards and years, shriveling can affect more than half of the crop," says Mark Krasnow, who was a postdoctoral student at UC Davis and is now at the Eastern Institute of Technology in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand. "In some years and some sites, wineries will decide not to harvest a vineyard due to the amount of shrivel. Fortunately this is rare."

The origins of SAD and BSN are a mystery, in spite of research investigations. Krasnow and his colleagues at UC ran a battery of high-tech tests to determine the factors involved, but found little consistency in results and to date, all tests for pathogenic organisms have been negative.

Whether due to SAD or BSN — berry shrivel occurs in vineyards all over the world, managed under different climates, making it a globally significant problem in winemaking.

"The irregularity of when and where (or if) SAD and BSN occur makes them very difficult to study," Krasner notes. Tests conducted by UC Davis Foundation Plant Services were negative for phytoplasmas, closteroviruses (leafroll), fanleaf viruses, nepoviruses and fleck complex viruses.

“It is possible that SAD has multiple causes, and that one of those causes might be a pathogen,” Krasnow says. “In some cases, all the fruit on a vine is affected, even clusters that appear outwardly normal. In other cases, it is only the symptomatic fruit that develops abnormally.”

Preliminary studies suggest that SAD can be propagated by chip budding, but vine-to-vine spread has not been seen, according to Krasnow. Future studies will focus on tests for a causal organism and a more careful examination of the metabolism of fruit affected by this disorder.

Bunchstem necrosis also varies in symptoms and whether effects occur on clusters or whole vines, and can occur at bloom or at ripening (veraison). Future studies will examine varietal differences in susceptibility having to do with xylem structure, the importance of concentrations of mineral nutrients, and other cultural factors.