Posts Tagged: beetle

Forest and tree health in a time of drought

The fourth winter in a row of disappointing precipitation has triggered a die off of trees in the Sierra Nevada, most of which is now in ‘exceptional drought' status. The US Forest Service conducted aerial monitoring surveys by airplane in April 2015 and observed a large increase in tree mortality in the Southern Sierra (from Sonora south). Surveyors flew over 4.1 million acres of public and private forest land and found that about 20 percent had tree mortality on it, totaling over 10 million dead trees.

The Forest Service found severe mortality in many pine species especially ponderosa pine. On private lands along the foothills of the Sierras, surveyors found extensive areas of dead pines. Large areas of blue and live oak mortality were also suspected though it was too early in the season to be sure.

On the Stanislaus National Forest, areas with dead trees doubled since last year. Pine mortality, mostly caused by western pine beetle, was common at lower elevations. Over 5 million trees were killed on the Sierra and Sequoia National Forests up from the 300,000 trees killed last year in the same area. Conifer mortality was scattered at higher elevation, though surveyors note that the survey was conducted too early in the year to detect the full extent of mortality levels.

The insects killing trees in the Sierra are all native insects that are multiplying because of drought conditions. Native insects are a necessary part of the forest ecosystem that speed decay of wood back into nutrients, prey on other insects, and provide food for wildlife. They are normally present at low levels and cause tree mortality only in localized areas.

However, drought weakens trees and reduces their ability to withstand insect attacks. Normally trees use pitch to expel beetles that attempt to burrow into the tree through the bark. Weakened trees cannot produce the pitch needed to repel these beetles which are able to enter under the bark and lay eggs. Larvae feed on a tree's inner bark cutting off the tree's ability to transport nutrients and eventually kill it. Attacking beetles release chemicals called pheromones that attract other beetles until a mass attack overcomes the tree. Many beetles also carry fungi that weaken the tree's defenses.

Western pine beetle is one of the main culprits killing pines in the Sierra during this drought. It is a bark beetle, one of a genus of beetles named Dendroctonus which literally means ‘tree-killer'. Adult beetles are dark brown and about a quarter-inch long. Adults bore into ponderosa pines, lay eggs which develop into larvae in the inner bark then complete development in the outer bark. When beetle populations are high, such as during drought periods, even healthy trees may not be able to produce enough pitch to ward off hundreds of beetle attacks.

Western pine beetle often attacks in conjunction with other insects. Other beetles causing tree mortality in Sierra forests include mountain pine beetle, red turpentine beetle, Jeffrey pine beetle, engraver beetles (Ips) and fir engravers. Forests with a higher diversity of tree species are typically less affected because beetles often have a preference for specific tree species. Some species may attack only one tree type. For example Jeffrey pine beetles attack only Jeffrey pine.

The best defense against bark beetles is to keep trees healthy so they are able fight off insects themselves. Widely spaced trees are typically less susceptible to successful attack by bark beetles since they face less competition for moisture, light, and nutrients compared to densely growing and overcrowded trees. Forest health can be promoted by thinning to reduce overcrowding (so each tree has access to more resources) and removing high risk trees during thinning (such as those that are suppressed or unhealthy).

For landscape trees of high value close to a home, watering may be one option to increase tree vigor against bark beetle attacks. Apply about 10 gallons of water for each inch of tree diameter (measured at chest height) around the dripline of the tree once or several times a month during dry weather.

There are some insecticides registered for bark beetle control, but all are preventative only. Carbaryl may prevent attack for up to two years, while pyrethroids can deter attack for up to a year. Spraying can be tricky because the chemical must be applied up to 50 feet up the trunk of the tree usually while standing on the ground. Since misapplication may have toxic consequences, any insecticide must be administered by a licensed pesticide applicator. All applications must follow the label. Though some systemic treatments applied to the soil or inserted into the tree may work in some cases, there is not a lot of documented evidence that they are effective against western pine beetle. No insecticide can prevent tree death once a tree has been successfully attacked.

Author: Susie Kocher, UC Agriculture and Natural Resources Cooperative Extension advisor

Decline of coast live oak trees in S. California is due to fungus

A fungus associated with the western oak bark beetle is causing a decline in coast live oak trees in Southern California by spreading “foamy bark canker disease.”

“We have found declining coast live oak trees throughout urban landscapes in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, Santa Barbara, Ventura and Monterey counties,” said Akif Eskalen, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology at the University of California, Riverside.

Eskalen recovered the fungal species, Geosmithia pallida, from tissues of infected coast live oak trees and performed pathogenicity tests on it in his laboratory at UC Riverside. The tests showed that the fungus is pathogenic to coast live oak seedlings and produces symptoms of foamy canker.

The western oak bark beetle, which spreads the fungus, is a small beetle — about 2 millimeters long — that burrows through the bark of the coast live oak tree, excavating shallow tunnels under the bark across the grain of wood. Brown in color, this beetle is native to California. Female beetles lay their eggs in the tunnels. It is not known at this time if the beetle infects trees other than coast live oak trees.

Symptoms of foamy bark canker disease include wet discoloration on the trunk and main branches of the infected coast live oak tree. This discoloration surrounds the entry holes that the western oak bark beetle makes to burrow into the tree. Multiple holes can often be seen on an infected tree.

“When you peel back the outer bark of the infected area, you see bark (phloem) necrosis surrounding the entry hole,” Eskalen said. “As the disease advances, a reddish sap may be seen oozing from the entry hole, followed by a prolific foamy liquid. This foamy liquid, the cause of which remains unknown, may run as far as two feet down the trunk.”

Eskalen explained that when the infection is at an advanced stage, the coast live oak tree dies. Currently, no control methods are in place to control the fungus or the beetle.

If you suspect your coast live oak tree has the symptoms described above, please contact your local UC Cooperative Extension advisor, pest control adviser, county agricultural commissioner's office or Eskalen at akif.eskalen@ucr.edu.

To see more photos, visit http://ucrtoday.ucr.edu/22096.

Mountain pine beetle turns trees into firewood

Tim Paine, professor in the UC Riverside Department of Entomology, discussed wood-boring beetles and wildfires during a six-minute interview on The Madeleine Brand Show, which is broadcast on KPCC, Southern California's public radio affiliate.

Mountain pine beetle is active from northern New Mexico to Northern British Columbia, Paine said.

"It has killed large numbers of trees in the whole range. in some places upwards of 90 percent of the trees are killed by the beetle. Its devastating," Paine said. "You see vast areas of gray ghosts of trees."

Mountain pine beetles bore through the outer bark of the tree and construct their feeding galleries underneath the bark, disrupting water movement through the tree and killing the tree in the process.

Paine said global climate change appears to be extending the mountain pine beetle's range.

"Apparently, in the higher elevations of the Rocky Mountains, temperatures warmed enough that the beetles are advancing up into higher elevations where they weren't before," Paine said.

Though beetles and fire are part of forests' natural eco-system for millennia, the landscape has been changed by long periods of human fire exclusion. Now, when these areas do burn, the fires are more intense than they would have been otherwise.

National trapping guidelines for walnut twig beetle released

The University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program has just published trapping guidelines for the detection of the walnut twig beetle. This tiny beetle, only several millimeters long, is the vector of the fungus that causes thousand cankers disease.

“The disease has killed thousands of black walnut trees in California’s landscape and is threatening commercial walnut trees as well,” said Mary Louise Flint, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Entomology at UC Davis and UC Statewide IPM Program.

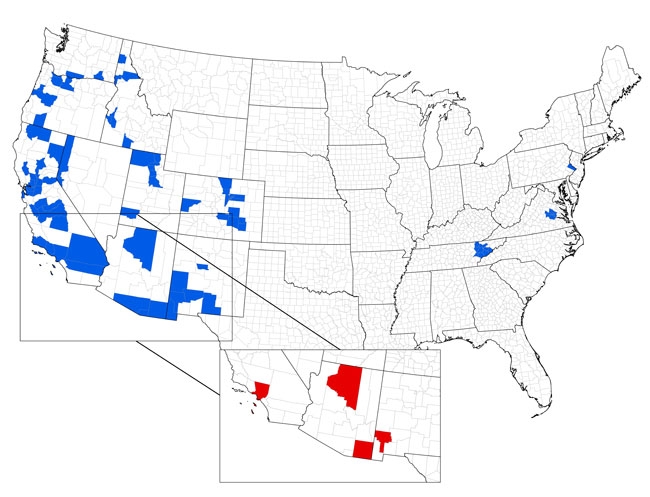

Thousand cankers disease has now moved into the eastern U.S., where it threatens valuable stands of black walnut timber east of the Mississippi. Once in trees, the beetle and fungus cause gradual decline and eventual death by killing the vital phloem tissue beneath the bark.

The guidelines and trapping methods were developed by a team of entomologists from UC Davis and the USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station in Davis. In 2010 and 2011, the scientific team discovered and patented an aggregation pheromone for the beetle and conducted scientific trials in northern California.

Late in the summer of 2011, they demonstrated the efficacy of the pheromone as a flight trap bait for detecting new populations of the beetle in Tennessee, Virginia and Utah. The demonstration-research project was extended to Pennsylvania in 2012. The bait lures both male and female beetles into a small plastic funnel trap. The team worked with a commercial partner, Contech Enterprises, Inc., to develop the technology.

As the eastern black walnut resource is valued at over $500 billion, the stakes are high for containing thousand cankers disease if it is introduced into key timber-producing states like Indiana and Missouri.

The study team is also using the traps and pheromone in research in California to learn more about biology and potential management strategies for the beetle in commercial walnut orchards and wildland areas.

The trapping guidelines are presented in a full-length document with color photographs and details on identifying the beetle, a short version for use in the field, and two video clips that demonstrate how to set up and service the traps. Find them at http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/thousandcankers.

In addition to Flint, members of the UC Davis and USDA scientific team and authors of guidelines are Steven J. Seybold, insect chemical ecologist, USDA Forest Service, based at Pacific Southwest Research Station in Davis; Paul L. Dallara, postdoctoral research scientist in the Department of Entomology at UC Davis; and Stacy M. Hishinuma, graduate student, Department of Entomology at UC Davis.