- Author: Michael D Cahn

- Author: Richard Smith

2018 UCCE Irrigation and Nutrient Management Meeting

Monterey County Agricultural Center

1432 Abbott Street, Salinas, CA

Tuesday, February 13

7:45 a.m. to 12:30 p.m.

7:45 Registration (Free)

8:00 Update on the Ag Order for the Central Coast.

Chris Rose, Senior Environmental Scientist, Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program Manager, Central Coast Water Board

8:30 Soil nitrogen dynamics in long-season vegetable crops

Richard Smith, Vegetable Crops Farm Advisor, Monterey County

9:00 Fall application of high C:N ratio amendments to immobilize soil nitrate

Joji Muramoto, Associate Researcher, Dept. of Environmental Studies, UCSC

9:30 On-farm trials evaluating the fertilizer value of nitrate in irrigation water

Michael Cahn, Irrigation and Water Resources Advisor, Monterey County

10:00 Break

10:30 On-farm management practices for mitigating insecticides in irrigation run-off

Laura McCalla, Department of Environmental Toxicology, UCD, Granite Canyon Laboratory

11:00 Microbial food safety risks of reusing tail water for production of leafy greens

Anne-laure Moyne, Staff Research Associate, Food Science and Technology Dept., UCD

11:30 Update on seawater intrusion in the Salinas Valley Aquifer

Howard Franklin, Senior Hydrologist, Monterey County Water Resources Agency.

12:00 Conclusion and Pizza Lunch

3.5 CCA & 0.5 DPR continuing education credits have been requested

- Author: Michael D Cahn

If you missed the 2015 Irrigation and Nutrient Meeting or you would like to review the presentations, you can download pdf versions of the powerpoint files from the UCCE Monterey County Website (http://cemonterey.ucanr.edu). The direct link to the presentations is:

http://cemonterey.ucanr.edu/Vegetable_Crops/2015_Irrigation_-_Nutrient_Management_Meeting_

We want to thank all of you who attended for your participation and for the many constructive comments that we received verbally and through the evaluation surveys. Let us know of any topics that you would like us to address in the next irrigation and nutrient management meeting or ways to improve the meeting.

If you are interested to learn more about CropManage for improving irrigation and nutrient management, I plan to host a hands-on training on using this on-line decision support tool on April 2nd. I will send out a formal announcement in the upcoming weeks.

- Author: Richard Smith

- Author: Michael D Cahn

Conversion between nitrate (NO3) and nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N):

|

To convert |

To |

Multiply by |

|

Nitrate (NO3) |

Nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N) |

0.22 |

|

Nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N) |

Nitrate (NO3) |

4.43 |

The reason for this conversion is that nitrate molecule weighs 62 grams per mole; the nitrogen content of nitrate is 22.5% of the total weight of the molecule.

Nitrogen content of irrigation water*

|

Water content of |

Multiply by |

To determine |

|

PPM NO3 |

0.052 |

Pounds N/acre inch |

|

PPM NO3 |

0.62 |

Pounds N/acre foot |

|

PPM N03-N |

0.23 |

Pounds N/acre inch |

|

PPM N03-N |

2.74 |

Pounds N/acre foot |

* water analyses from most labs report NO3 in units of ppm, but it is very important to pay attention to which units the results are reported.

How much of the nitrogen in water should be credited to your crop is debatable. Consider that lettuce transpires 5 to 8 inches of water between germination and maturity in the Salinas Valley during the summer. Extra water applied beyond crop ET would be lost as drainage and therefore would not contribute N to the crop. The extra water also would likely leach plant available soil nitrate below the root zone. In addition, some ground water that is high in nitrate is also high in salts and may require a leaching fraction (extra water applied to leach salts below root zone) to attain maximum production. The good news is that you can account for the N contribution from the nitrate in the irrigation water using the quick nitrate soil test for previous irrigations. However, this test will not estimate the contribution of N from the irrigation water for future waterings.

Our best estimate of how much N the irrigation water would contribute to future waterings is to divide the crop evapotranspiration by the irrigation efficiency. For example, for 7 inches of crop ET and an 80% irrigation efficiency, the following values would approximate the N contribution of irrigation water for the indicated range of nitrate concentrations:

|

Nitrate (NO3) concentration in irrigation water |

Nitrate (NO3-N) concentration in irrigation water |

Lbs nitrogen/A in seven inches of irrigation water taken up by lettuce* |

|

45 |

10 |

13 |

|

89 |

20 |

25 |

|

177 |

40 |

51 |

|

266 |

60 |

76 |

* multiplied by 0.8 to account for the irrigation system efficiency

As can be seen, waters containing less than 45 ppm NO3 generally do not contribute a significant amount of nitrogen for crop growth. However, if well waters contain more than that amount they begin to contribute greater amounts of water for crop growth.

- Author: Richard Smith

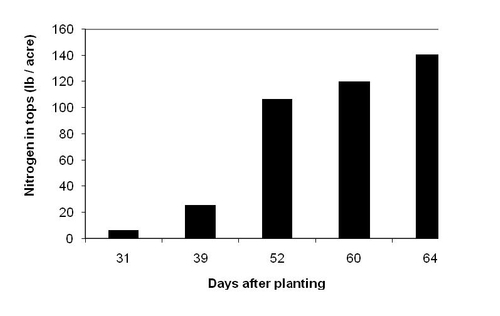

Nitrogen use to grow vegetables along the Central Coast is the subject of proposed regulations by the Regional Water Quality Control Board (RWQCB). As a result there is increased interest in improving the efficiency of applied nitrogen (N) fertilizer. Understanding the uptake pattern of lettuce is critical to careful N management. Lettuce typically takes up 120-140 lbs of nitrogen in the above ground biomass with the higher uptake levels occurring on 80 inch beds with 5-6 seedlines. The uptake patterns of romaine and head lettuces are similar. Figure 1 shows the uptake of N in a lettuce crop over the growing season. At thinning (app. 31 days after planting) the crop had taken up less than 10 lbs N/A. The biggest increase in nitrogen uptake by the crop occurred between 39 days and 52 days after planting. The most difficult task in managing nitrogen fertilization of lettuce is to supply adequate levels of nitrogen during this period of high demand by the crop, but to not leach it during irrigations.

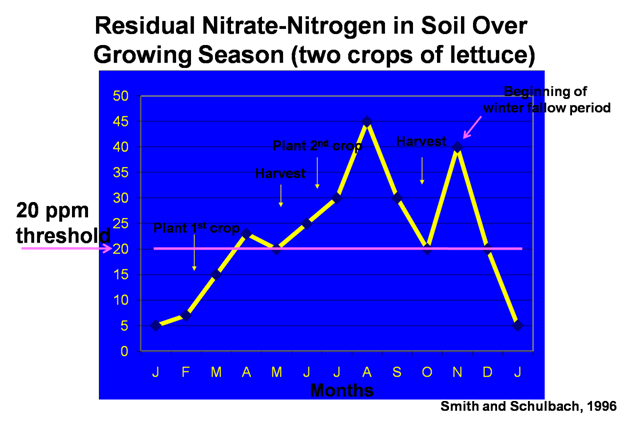

In second crop lettuce it is possible to take advantage of residual soil nitrate and use it in place of applied fertilizer. Figure 2 shows a typical pattern of nitrate-N levels in Salinas Valley soils. The data indicates that typically by the time you get to the second crop, levels of residual nitrate-N can increase above 20 ppm (which is equivalent to 80 lbs N/A) due to left over N applied to the prior crop and mineralization of nitrate-N from crop residue. Whatever the source of the residual nitrate-N, it is a substantial quantity that can be utilized by a growing lettuce crop.

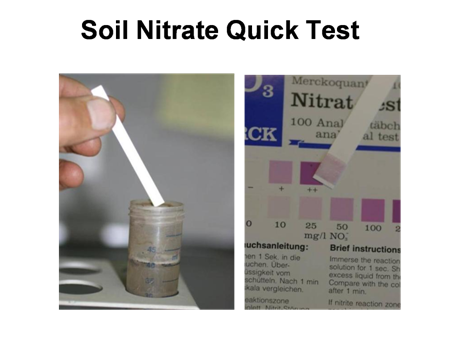

Residual soil nitrate can be monitored by use of the soil nitrate quick test (see photo 1). The test provides information on levels of soil nitrate-N and can help you to decide whether you need to apply fertilizer as planned or if you can reduce This test is most effective if done at thinning to determine residual soil nitrate levels for the first post thinning fertilization and can be done again prior to subsequent fertilizer applications if desired.

|

Figure 1. Nitrogen uptake by lettuce over the growing season. |

|

Figure 2. Nitrate-N in soil over the course of the growing season January to December – mean of six fields |

Photo 1. Soil nitrate quick test

- Author: Richard Smith

- Research Assistant: Aaron Heinrich

Nitrate leaching from vegetable production along the Central Coast is under greater scrutiny and is the subject of proposed regulations by the Regional Water Quality Control Board (RWQCB). The regulations as written have stipulated that leachate from agricultural lands should not exceed the public health limits for nitrate in drinking water of 10 ppm nitrate-nitrogen.

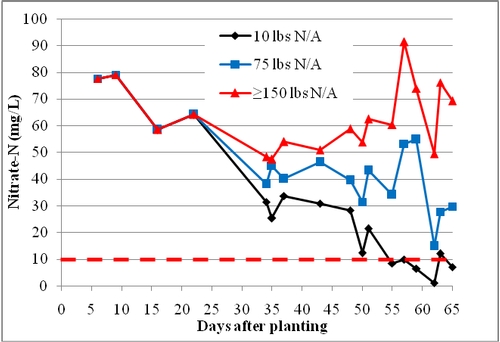

To date there has been little information developed on the quantities of nitrate contained in leachate from lettuce production. In 2009 we conducted a nitrogen fertilizer trial in which we applied 10, 75, 150, 225 and 300 lbs of N/A and water was applied at 116% of evapotranspiration. In order to measure leachate from the plots, suction lysimeters were installed to a depth of 2 feet deep in the soil (photo 1). During each irrigation, suction in the lysimeters was maintained at 20-25 centibars which was assumed to be the leachable fraction of soil water. After each irrigation, leachate was collected and analyzed for nitrate concentration.

The 10 lbs N/A was a low N treatment (and yielded substantially lower than other treatments), but even in this treatment had leachate nitrate-N concentrations substantially greater than the 10 ppm nitrate-N drinking water standard (see graph below) for the majority of the early season. The concentration of nitrate-N in this treatment declined to below the drinking water standard for the final third of the growing season. These data give us a glimpse into nitrate levels of leachate from vegetable production fields. Even treatments with little applied N can have substantial quantities of nitrate in the leachate. This indicates that monitoring of the concentration of nitrate in the leachate may not be a consistently useful tool for understanding the quantity of N leached.

Figure 1: Nitrate-N concentrations in leachate over the growing season of romaine lettuce (for simplicity, we pooled the leachate nitrate levels of the highest three nitrogen fertilizer treatments 150, 225 and 300 lbs N/A, as they were not significantly different from each other)