Posts Tagged: Hispanic

Farmers of color share their contributions, concerns in UC SAREP webinar series

When agricultural advisors came to the Cochiti Pueblo in New Mexico during the 1940s, they lined the irrigation ditches with concrete, in the name of boosting efficiency and productivity. But in single-mindedly focusing on water delivery, they neglected to consider how the previously inefficient seepage sustained nearby fruit trees.

Their actions, as well-intentioned as they might have been, disrupted the local ecosystem and killed the trees that had fed many generations, according to A-dae Romero-Briones, who identifies as Cochiti and as a member of the Kiowa Tribe.

“In my language, we call the extension agents ‘the people who kill the fruit trees,'” said Romero-Briones, director of the Food and Agriculture Program for the First Nations Development Institute, a nonprofit that serves Tribal communities across the mainland, Alaska and Hawaii.

The historically tense relationship between Indigenous peoples and government-affiliated programs is one of the many complex dynamics discussed in a six-part webinar series, “Racial Equity in Extension,” facilitated by UC Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program.

Making communities of color in the agricultural sector more visible is a priority for Victor Hernandez, a sociologist and outreach coordinator for the USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service. Hernandez, who has organized “Growing Together” conferences for Latino and Black farmers, is trying to get more farmers of color to participate in the upcoming 2022 Agricultural Census.

“If we cannot quantify the demographic, we cannot justify the need,” emphasized Hernandez, explaining that his office uses the data to direct resources that advance equity in service, program delivery and distribution of funds.

A legacy of mistrust

At the same time, however, Hernandez also acknowledged the challenges in registering growers of color for the census, conducted by the USDA's National Agricultural Statistics Service. (According to Brodt, USDA's most recent agricultural census, dating to 2017, counts approximately 25,000 producers of color among 128,535 total producers in California.)

“Many of us that are considered socially disadvantaged or historically underserved…a lot of times our peoples come from [nations with] oppressive governments,” Hernandez said. “And so when you come to the United States and you begin to build your life here, to go and engage with the federal government is not the first knee-jerk reaction.”

On top of government mistrust and fears of deportation or detention, other immigrant groups have seen mainstream agriculture – borne by the “Green Revolution” wave across the globe – replace deep-rooted cultural practices, said Kristyn Leach of Namu Farm in Winters.

“It just makes these small farmers distrust our own knowledge, the knowledge that's existed for centuries – before the kind of current iteration of agriculture that we're situated within right now,” said Leach, who works to preserve the agricultural heritage of her Korean ancestors, and facilitates a farmers' collaborative called Second Generation that adapts Asian crop varieties to climate change.

According to Romero-Briones, a collective memory of supplanted culture also lingers in Indigenous communities. In the Cochiti Pueblo, “primarily a subsistence agriculture community” with a long history of corn cultivation, their practices are distinct from those in the mainstream – including regenerative and sustainable agriculture.

Building relationships takes commitment

Given that legacy of cultural displacement and appropriation, how do extension professionals and other agricultural advisors slowly rebuild trust with communities of color? For Romero-Briones, it begins with a genuine respect for Indigenous practices, and she urges interested people to contact their local tribal historic preservation officer to begin strengthening those connections and understanding – beyond a couple of phone calls.

“As someone who works with Indigenous people all day, even I need to recognize sometimes I have to meet with people up to 12 times before we actually start talking about the work that I initially wanted to talk to them about,” Romero-Briones said.

In a similar vein, Chanowk Yisrael, chief seed starter of Yisrael Family Farms, encouraged listeners to reach out to members of the California Farmer Justice Collaborative – an organization striving for a fair food system while challenging racism and centering farmers of color.

“To use a farm analogy: we've got this ground, which is the farmers of color who have been neglected for a long period of time,” said Yisrael, who has grown his farm in a historically Black neighborhood of Sacramento into a catalyst for social change. “It's not just going to be as simple as just throwing some seeds and things are going to come up; you're going to have to do more – that means you got to get out and do much more than you would do for any other community.”

Investing time in a community is one thing – and backing it up with tangible resources is another. Technical expertise is only the “tip of the iceberg,” Leach said, as historically marginalized groups are also seeking land access and tenure, more affordable cost of living, and access to capital.

“All of those things are actually much bigger burdens to bear for most communities of color than not having the knowledge of how to grow the crops that we want to grow, and not knowing how to be adaptive and nimble in the face of climate change," Leach explained, highlighting California FarmLink as an essential resource. (The “Understanding Disparities in Farmland Ownership” webinar includes a relevant discussion on this subject.)

Bringing diverse voices to the table

Another key is ensuring that farmers and farm workers of color are represented in management and decision-making processes. Samuel Sandoval, a professor in the UC Davis Department of Land, Air and Water Resources and UC Cooperative Extension specialist in water management, develops outreach programs in English and Spanish for everyone from farm workers to the “boss of the boss of the boss.”

“It has to be changed,” he said, “because at the end, the person who is going to operate the irrigation system and turn on or off the valves, the person who is looking if there's a leak or not – that's the person who's not being informed, or has not been informed on purpose.”

That exclusion of certain groups can lead to a loss of invaluable knowledge. Leach said there is a real danger in ignoring the wisdom of communities that have contributed so much to the foundation of food systems in California and around the globe.

“These really kind of amazing, sophisticated and elegant agroecological systems that we don't often legitimize through the scientific language and perspectives aren't seen as being really technically proficient – but, in many ways, they're more dynamic and more resilient than the things that we're perpetuating right now,” she said.

As a concrete example, Sandoval said that while extension advisors and specialists conduct studies to remedy a plant disease, farm workers might be developing – separately and in parallel – their own solutions by asking for advice from their social networks via WhatsApp, a phone application.

A reimagining of collaboration, Sandoval said, would include (and compensate) people working in the field for sharing their perspectives – bringing together academics and farmers, integrated pest management experts and pesticide applicators, irrigation specialists and those who do the irrigation.

A need to look within

Concerns about inclusion and validating alternate sources of knowledge apply also to the recruitment process in extension. Leach said that she has seen listings for advisor jobs that would require, at a minimum, a master's degree – which would automatically disqualify her, despite her extensive knowledge of Asian heirloom vegetables.

“When you look at a job description and you see ‘Asian crop specialist,' only required qualification is a master's degree, and then somewhere down the long list of sort of secondary desired, recommended things is some knowledge of Asian crops or communities…you know that just says a lot in terms of what has weight,” Leach explained.

Before organizations can authentically connect with communities of color, they should prioritize diversity in their own ranks, said Romero-Briones. First Nations Development Institute had to ensure that they had adequate representation across the many Tribes that they serve.

“Before we start looking out, we have to start looking in,” she explained, “and that means we have to hire Indigenous people who know these communities.”

For extension professionals and other members of the agricultural community in California, the UC SAREP webinar series has helped spark that introspection and a meaningful reevaluation of institutional processes and assumptions.

“These discussions have been tremendously illuminating and eye-opening,” Brodt said. “But hearing and learning is just the start – it's incumbent on us, as an organization and as individuals, to take action to ensure that farmers of color and their foodways are truly respected and valued.”

The “Racial Equity in Extension” series is made possible by professional development funds from Western Sustainable Agricultural Research and Education.

Why we celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month

Hispanic Heritage Month begins on September 15 and continues until October 15. The purpose of the celebration is to recognize the contributions and vital presence of Hispanics and Latin Americans in the United States.

President Lyndon Johnson first approved Hispanic Heritage Week in 1968 and expanded to a full month by President Ronald Reagan in 1988. Finally, Hispanic Heritage Month was officially enacted as a law on August 17, 1988.

Why is Hispanic Heritage Month held from mid-September to mid-October? It was chosen in this way to reserve two significant dates for Spanish-speaking countries. On the one hand, Independence Day is celebrated in countries such as Mexico, Chile, and five Central American nations (Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Costa Rica).

Also, Columbus Day or Día de la Raza was commemorated, a date celebrated more by Italian-Americans than Spanish-speaking immigrants.

Hispanics and Latinos in the United States are getting stronger every day; it is undeniable. But they are more recognized for their culinary richness and the attractiveness of their rhythms, such as Mariachi, salsa, cumbia, mambo, and merengue, than for their essential contributions the professional level. Although, at the national level, there are all kinds of professionals who, with their work, have contributed to the cultural, social, and economic wealth of this country.

Hispanics who have helped improve our lives range from an astronaut to a winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Luis Walter Alvarez, born in Mexico and naturalized American, was an experimental physicist, inventor, and professor who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968.

Franklin Ramón Chang Díaz is a Costa Rican mechanical engineer, naturalized American, physicist, and former NASA astronaut.

Ellen O. Ochoa is an engineer born in Los Angeles, CA, to Mexican parents, who became the first Hispanic woman to travel to space and was a former director of the Johnson Space Center.

Did you know that, according to the Census Bureau, there are 60 million Hispanics in the country? And that more than half live in three states: California, Texas and Florida? Two-thirds of Hispanics in the United States have their origins in Mexico, followed by Puerto Rico (9.5%) San Salvador (3.8%), and Cuba (3.6%). The rest come from the twelve countries where Spanish is the official language.

According to the Census Bureau, college enrollment has increased over the past decade, and 49% of Hispanic high school graduates enrolled in a university. The U.S. Department of Education recognizes six University of California campuses as institutions serving Hispanic students, including UC Irvine, while UC Merced is one of the universities in the country with the highest percentage of Hispanic students.

UC Agriculture and Natural Resources joins the celebration

This year UC ANR the celebration by recognizing three Latino professionals who serve their communities while always upholding UC ANR's public values of academic excellence, honesty, integrity, and community service.

Claudia Diaz - 4-H youth development advisor for Riverside and San Bernardino counties. Claudia has received numerous awards and recognitions for her work with underprivileged youths in urban areas. She has been with UC ANR for five years.

Sonia Ríos - Subtropical horticulture advisor for Riverside and San Diego counties. Since an early age, Sonia knew her future was in agriculture, her grandfather and her father worked in agriculture and taught her the love for nature and the fields. She has been with UC ANR for almost nine years.

Javier Miramontes - Nutrition program supervisor for Fresno County. Javier enjoys the opportunity his work gives him to serve the community where he grew up. He finds it very rewarding to teach parents, senior citizens, and Highschool students about the importance of a healthy diet and how to create a sustainable environment. He has been with UCANR for over five years.

UC joins commemoration of National Hispanic Heritage Month

National Hispanic Heritage Month is Sept. 15 to Oct. 15. The observation started as Hispanic Heritage Week in 1968, and was expanded to 30 days by Pres. Reagan in 1988, to recognize the contributions of Hispanics and Latinos to the United States.

UC Cooperative Extension joins in the commemoration by sharing a sampling of its recent efforts to reach California Hispanics and Latinos. For more information about UCCE outreach to Hispanic and Latino communities in California, see UC ANR News and Information Outreach in Spanish.

CalAgrAbility helps disabled farmers and farmworkers stay in agriculture

Working on a farm is among the most dangerous of professions. “It's more dangerous to work in agriculture than in the police force,” said Esmeralda Mandujano, an educator for the UC CalAgrAbility program, located in Davis. CalAgrAbility is part of a nationwide effort funded by the USDA that supports agricultural workers with chronic disabilities or who have been injured on the job. Some conditions are very common, such as arthritis, deteriorating vision, hearing loss or mobility problems. Other ag folks face other challenges, such as amputations or spinal injuries. "We believe that solutions exist, and we are willing to do all we can to connect people with solutions that will give more control over their lives," Mandujano said. "We don't give out money, but we help them find ways to meet their needs." Bilingual staff members help locate resources, including low-cost modifications to the farm, home, equipment and work site operations. CalAgrAbility also provides technical assistance, education and training. For more information, contact Esmeralda Mandujano at (530) 753-1613, calagra@ucdavis.edu.

UCCE helps Hispanic farmers pursue the American Dream

Urban students give fresh ideas for conserving creek

Chollas Creek, which drains to San Diego Bay, is affected by pollution and choked by an infestation of invasive Arundo donax (giant cane). Community groups have removed Arundo, planted native species, and installed walkways, seating, shade structures and art to make the restoration areas attractive for outdoor activities. But the urban area around the creek, which has high population density and a high crime rate, continues to suffer from environmental degradation. To find out what young community members think about Chollas Creek and its surrounding outdoor areas, UC Cooperative Extension met with 35 youths from 5th through 12th grades from the neighborhood, including 31 from Latino cultural groups and four African Americans. Leigh Taylor Johnson, UC Cooperative Extension advisor in San Diego, asked the young people why the creek is important to them and to suggest ways to conserve water, reduce pollution and prevent the Arundo donax from infesting the creek. “I am in the process of analyzing the results,” Taylor Johnson said. “In general, I was very impressed with the insights and creative recommendations provided by the youthful participants.” Groundwork San Diego – Chollas Creek, Jacobs Center for Neighborhood Innovation and Jackie Robinson YMCA partnered in this research. For more information, contactLeigh Taylor Johnson at (858) 822-7802, ltjohnson@ucanr.edu.

Resources available in Spanish for managing pests and applying pesticides safely

Southern California landscapers get pest management training in Spanish

An estimated 12,000 to 15,000 Spanish-speaking landscapers in San Bernardino County lack adequate expertise in integrated pest management (IPM) and safe use of pesticides, in part due to the rarity of training opportunities using the Spanish language. UC Cooperative Extension advisor Janet Hartin wanted to change this, and received a $125,000 competitive grant from the Department of Pesticide Regulation to expand integrated pest management education to Southern California Spanish-speaking landscapers. The project focuses on reducing groundwater and surface water pollution leading to water quality degradation due to overuse and improper use of pesticides and fertilizers. This grant funded educational services to Spanish-speaking landscapers at 13 workshops and hands-on as well as classroom training in 2013. Increasing educational services stressing pest prevention to this large clientele – which has quadrupled over 20 years – can significantly reduce overuse and misuse of pesticides in urban environments and improve the health and safety of the work environment for this important segment of the profession. For more information, contact Janet Hartin, (951) 313-2023, jshartin@ucanr.edu.

Mexico native to provide culturally sensitive nutrition programs to California Latinos

¡Salsa! It’s more than a flavorful condiment

Salsa plays a much-deserved starring role in Mexican cuisine, adding not only refreshing and spicy flavors to breakfast, lunch, snacks and dinner, but also conveying an ample supply of nutrients.

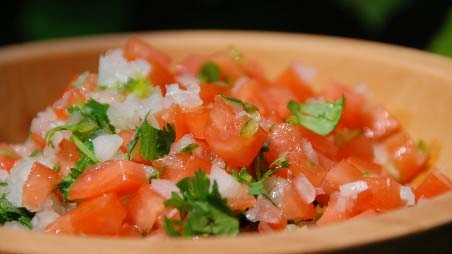

A blend of fruits, vegetables and seasonings, salsas are created almost entirely from the foods highly recommended by nutrition experts, says UC Cooperative Extension nutrition educator Margarita Schwarz.

“Experts recommend we eat 3 to 5 servings of vegetables and 2 to 4 servings of fruit daily and salsa is an excellent way to add these foods to our diets,” she said. “We can experiment in the kitchen with different blends, combining flavors that are sweet, acid and picante to create a dish that’s delicious and healthful.”

Schwarz said there are a wide variety of salsas:

- Fresh salsa (also known as pico de gallo, which in Spanish is literally “rooster’s beak”) is made with chopped tomato, chili pepper, onion, cilantro, lime juice, salt and pepper

- Salsa ranchero uses similar ingredients but the mixture is blended or grinded until almost smooth

- Salsa verde (green salsa), in which the main ingredient is tomatillo, a tart fruit related to cape gooseberries

- Guacamole is a sauce with avocado as the base

- Mole is a dark-colored sauce made of roasted chili peppers, spices, chocolate and sometimes squash seeds

- Corn salsa combines fresh salsa ingredients with a generous amount of cooked corn kernals

- Mango salsa is a chunky, colorful blend that combines the sweet, tropical taste of mango fruit with onions and spices

In the late 1990s, it was widely reported that salsa sales surpassed ketchup sales in U.S. grocery stores. That’s a good thing. Ketchup contains sugar, and salsa generally has none. Salsa is low in calories and contains little to no fat. The tomatoes, chilies and cilantro in salsa have vitamins A and C and the tomatoes contribute potassium to the diet. The avocado in guacamole contains fiber, vitamin B6, vitamin C and potassium.

“Sometimes people will say: ‘I don’t eat avocados because they have fat,’ but this is the fat that the body needs and that can help prevent cardiovascular disease,” Schwarz said

Salsa is the Spanish word for sauce, but the mixture was a staple of Latin American indigenous cuisine long before the Spanish conquest. Tomato, avocado, tomatillo and many hot peppers are native to Central and South America.

The other “salsa,” a popular Latin dance, is also good for the heart, Schwarz said. The salsa originated in Cuba and Puerto Rico, but all of Latin America has incorporated it into their musical lexicon. Salsa’s fast tempo makes it such a lively physical activity, some health clubs offer salsa classes for aerobic exercise.

Mango Salsa

Following is a mango salsa recipe from the UC Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program curriculum:

Ingredients:

1 mango, peeled, pitted and diced (or 1 cup thawed frozen mango chunks)

1 tablespoon diced red onion

1 tablespoon chopped fresh or dried cilantro (optional)

¼ teaspoon salt

Juice of 1 lime or 2 tablespoons bottle lime juice

Directions:

- Combine all ingredients in a bowl

- Serve with baked tortilla chips or us as a garnish for chiken or fish.