Posts Tagged: oak

California Oak Symposium to attract hundreds of oak researchers to Visalia Nov. 3-6

The foremost oak researchers in California and the Pacific Northwest, plus researchers from Spain and South Korea, converge in Visalia for the 7th California Oak Symposium Nov. 3-6. This is the symposium's first appearance in the San Joaquin Valley since its inception 35 years ago.

"The drought will be a major focus of the symposium," said Rick Standiford, UC Cooperative Extension forest management specialist based at UC Berkeley, and symposium coordinator. "We will also have cutting edge research and policy presentations on sudden oak death, gold-spotted oak borer and conifer encroachment in black and Garry oak woodlands, among much more."

California's oak woodlands cover 10 percent of the state, and oaks are a key ecological component of conifer forests. There are more than 20 species of native California oaks; several are found nowhere except within the state's borders and some others range only as far as Canada and Mexico. Oak woodlands are the most biologically diverse habitat in the state, making conservation a policy and management priority.

The symposium begins with tours of regional oaks on Nov. 3. One group will tour the Visalia urban oak forest; a second group visits the Kaweah Oaks Preserve and Dry Creek Preserve. Over three days, scientists will present 58 research papers on oak management, wildlife, ecosystem services, ranching and utilization, gold-spotted oak borer, oak restoration, and sudden oak death. Ten of the projects focus on oak conservation, touching on such topics as economic incentives for oak conservation, the oak conservation program at Tejon Ranch, and establishment of Oregon white oak and California black oak in northwestern California.

The wildlife series of presentations provides new information about native and introduced species that make their homes among the oaks, including European starlings, Pacific fishers, bats and wild pigs. Some of the ranching topics to be discussed include the public and private incomes from forests in Andalusia, Spain, economic incentives related to recreational use of private oak woodland, and acorn production and utilization in South Korea.

Since 1979, the California Oak Symposium has been held every 5 to 7 years; the last one was in Rohnert Park in 2006. Visalia was selected for the symposium because of its geographic convenience for both northern and southern California oak scientists, and the city's commitment to the preservation and protection of native oak trees.

Decline of coast live oak trees in S. California is due to fungus

A fungus associated with the western oak bark beetle is causing a decline in coast live oak trees in Southern California by spreading “foamy bark canker disease.”

“We have found declining coast live oak trees throughout urban landscapes in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, Santa Barbara, Ventura and Monterey counties,” said Akif Eskalen, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology at the University of California, Riverside.

Eskalen recovered the fungal species, Geosmithia pallida, from tissues of infected coast live oak trees and performed pathogenicity tests on it in his laboratory at UC Riverside. The tests showed that the fungus is pathogenic to coast live oak seedlings and produces symptoms of foamy canker.

The western oak bark beetle, which spreads the fungus, is a small beetle — about 2 millimeters long — that burrows through the bark of the coast live oak tree, excavating shallow tunnels under the bark across the grain of wood. Brown in color, this beetle is native to California. Female beetles lay their eggs in the tunnels. It is not known at this time if the beetle infects trees other than coast live oak trees.

Symptoms of foamy bark canker disease include wet discoloration on the trunk and main branches of the infected coast live oak tree. This discoloration surrounds the entry holes that the western oak bark beetle makes to burrow into the tree. Multiple holes can often be seen on an infected tree.

“When you peel back the outer bark of the infected area, you see bark (phloem) necrosis surrounding the entry hole,” Eskalen said. “As the disease advances, a reddish sap may be seen oozing from the entry hole, followed by a prolific foamy liquid. This foamy liquid, the cause of which remains unknown, may run as far as two feet down the trunk.”

Eskalen explained that when the infection is at an advanced stage, the coast live oak tree dies. Currently, no control methods are in place to control the fungus or the beetle.

If you suspect your coast live oak tree has the symptoms described above, please contact your local UC Cooperative Extension advisor, pest control adviser, county agricultural commissioner's office or Eskalen at akif.eskalen@ucr.edu.

To see more photos, visit http://ucrtoday.ucr.edu/22096.

Don’t move firewood and pests

“Buy firewood from a local source close to your home to prevent the spread of insects and diseases, such as the goldspotted oak borer, sudden oak death and emerald ash borer,” said Tom Scott, a UC Cooperative Extension specialist based at UC Riverside who studies these invasive pests.

“Firewood is one of the least-regulated natural resource industries in California,” said Scott, “but this is a situation where the university can play a critical role in changing behavior through research and education rather than regulation.”

Scott and his UC Cooperative Extension colleagues are working with the U.S. Forest Service, the California Firewood Task Force and other agencies to educate and discourage woodcutters, arborists, firewood dealers and consumers from transporting infested wood.

“Many people don’t realize that firewood can harbor harmful insects and plant pathogens. Moving around infested wood can introduce those pests and pathogens to new areas where they might take hold and could have devastating impacts to trees, our natural resources and local communities,” said Don Owen, California Firewood Task Force chair and CAL FIRE forest pest specialist based in Redding.

“Even wood that looks safe can harbor destructive pests,” cautioned Janice Alexander, UC Cooperative Extension sudden oak death outreach coordinator in Marin County.

For example, female goldspotted oak borers lay eggs in cracks and crevices of oak bark, and the larvae burrow into the cambium of the tree to feed so they may not be visible.

The goldspotted oak borer has killed more than 80,000 oak trees in San Diego County in the last decade and Scott hopes it can be contained in that region. The half-inch-long beetle is native to Arizona but not to California and likely traveled in a load of infested firewood, according to Scott.

In his research, Scott has found outbreaks of goldspotted oak borer 20 miles from the infested area, which leads him to believe movement in firewood is the most likely reason for the beetle leap-frogging miles of healthy oak woodlands to end up in places like La Jolla. In communities where people harvest local trees for firewood, oaks have remained relatively beetle-free, Scott said.

In addition to concealing goldspotted oak borer, firewood may harbor other destructive invasive species such as emerald ash borer or the pathogen that causes sudden oak death. Sudden oak death has killed more than a million oak and tanoak trees in 14 coastal California counties, from Monterey to Humboldt. The highly destructive emerald ash borer has been identified in Michigan, Indiana, Ohio and Illinois, but not California.

“Our best defense against the GSOB outbreak is the enlightened self-interest of Californians purchasing firewood,” Scott added. “If you want to protect the oaks around your house, neighborhood, and nearby woodlands, make sure that you’re not buying wood that could contain these beetles.”

In a broader sense, buy firewood from reputable dealers, from local sources whenever possible – and try to make sure that the wood you buy has been properly seasoned and doesn’t contain pests.

Tips for buying oak firewood

- Don’t buy green firewood from unknown sources, it has the highest chance of containing pests and pathogens.

- Ask where the firewood originated. If it isn’t local, ask what precautions the seller has taken to ensure that the firewood is free of harmful insects and disease or consider buying from another local source.

- Wood should preferably be bark-free, or have been dried and cured for one year prior to movement.

- If you see D-shaped exit holes, be reluctant to buy unless you know the wood has dried for at least a year or longer.

For more information about the pests and diseases that threaten California’s oaks, visit these websites:

Sudden oak death disease has killed over a million trees in California.

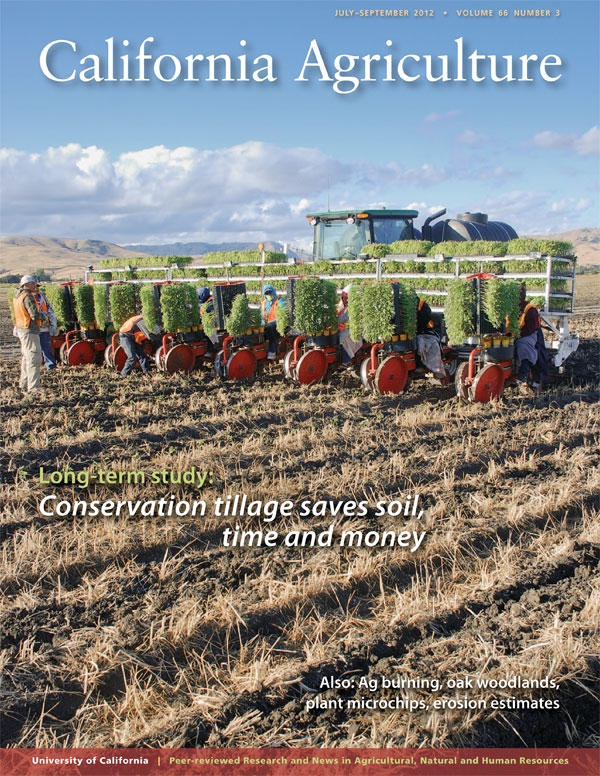

Long-term study: Conservation tillage saves oil, soil and toil in cotton

A 12-year study published in the July-September 2012 issue of the University of California’s California Agriculture journal demonstrates that cotton grown in rotation with tomatoes — using lower-impact conservation tillage — can achieve yields similar to standard cultivation methods and at lower cost.

Conservation tillage seeks to reduce the number of times that tractors cross the field, in order to protect the soil from erosion and compaction, and save time, fuel and labor costs. Cotton crops are planted directly into stubble from the previous crop in the rotation.

In the study, conducted from 2000 to 2011 at the UC West Side Research and Extension Center in Five Points (southwest of Fresno), the number of tractor passes for a cotton-tomato rotation grown with a cover crop was reduced from 20 in the standard treatment to 13 with conservation tillage.

By the final years of the in the San Joaquin Valley study, cotton lint yields were statistically equivalent and even higher (in 2011) than with standard cultivation methods.

“The UC studies have consistently shown that conservation tillage can yield as well as standard tillage in a cotton-tomato rotation,” lead author Jeffrey P. Mitchell, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Plant Sciences at UC Davis, and co-authors wrote in California Agriculture journal.

Their study, “Conservation tillage systems for cotton advance in the San Joaquin Valley,” as well as the entire July-September 2012 issue of California Agriculture journal, can be viewed and downloaded online at: http://californiaagriculture.ucanr.edu.

Mitchell is a founder of Conservation Agriculture Systems Innovation (CASI), a diverse group of more than 1,800 farmers, industry representatives, UC and other university faculty, and members of the Natural Resources Conservation Service and other public agencies (http://ucanr.edu/CASI). CASI defines conservation tillage as a suite of cultivation practices — including no-tillage, minimum tillage, ridge tillage and strip tillage — that reduce the volume of soil disturbed and preserve crop residues in the field. Conservation tillage is common in other regions of the United States and parts of the world and is beginning to gain acceptance in California agriculture.

Technological upgrades to tillage implements have been critical to the advancement of conservation tillage systems. These include equipment that can target operations to just the plant row rather than the whole field as well as accomplish several operations at the same time.

Fuel use was reduced by 12 gallons and labor by 2 hours per acre in the conservation tillage plots. This amounted to savings of about $70 per acre in 2011 dollars.

Mitchell noted that more research is needed on the adequate development of cotton stands and the prevention of soil compaction under different conditions, but that the benefits of conservation tillage are becoming increasingly obvious. “Provided that yield performance or more importantly bottom-line profitability can be maintained and the risks associated with adopting a new tillage system are deemed reasonable, conservation tillage systems may become increasingly attractive to producers and more common in San Joaquin Valley cotton-growing areas.”

Also in the July-September 2012 issue of California Agriculture:

Agricultural burning and air quality: Southern California farmers in Imperial County regularly burn crop residues of bermudagrass in the winter and wheat stubble in the summer. A study of ambient air quality adjacent to and downwind of agricultural burning sites in the desert county found that particulate matter levels (PM2.5) were 23% higher on burn days than on no-burn days at four locations. Researchers from the California Department of Public Health also assessed community educational needs regarding agricultural burning and developed fact sheets in English and Spanish targeting the general public, schools and farmers.

The value of privately owned oak woodlands: More than 80 percent of California’s 5 million oak woodland acres are privately owned. In a survey, researchers from Spain and UC Berkeley asked private owners of California oak woodlands to place a monetary value on amenities from their land such as recreation, scenic beauty or a rural lifestyle. The technique, called “contingent valuation,” found that landowners would be willing to pay $54 per acre annually for private amenities from their land and that their willingness to pay per acre decreased as their property size increased.

Microchips for woody plants: Radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags are widely used to track books in libraries, products during manufacturing, cattle from rangeland to the slaughterhouse, inventory in retail, runners in road races and much more. These tiny microchips (often the size of a grain of rice) are now being placed in woody plants such as grapevines and orchards to monitor crop diseases, track irrigation and pesticide applications, and help prevent the theft of valuable plants. In this review, Italian researchers discuss the emerging uses of RFID technology in agriculture.

Rainfall simulators to measure erosion: In their efforts to keep Lake Tahoe clear, researchers have been studying the movement of sediments into the lake using rainfall simulators. These fairly simple machines are placed on a slope; “rain” is created over a small frame, which allows sediment in the runoff to be collected and measured. However, the lack of standardization in erosion studies using rainfall simulators may be hampering progress. Mark Grismer, professor in the Department of Land, Air and Water Resources at UC Davis, makes the case for standardized field methodologies and data analysis.

###

California Agriculture is the University of California’s peer-reviewed journal of research in agricultural, natural and human resources. For a free subscription, go to: http://californiaagriculture.ucanr.edu, or write to calag@ucanr.edu.

WRITERS/EDITORS: To request a hard copy of the journal, e-mail jlbyron@ucanr.edu.

Local agencies, landowners team up to stop SOD spread in Humboldt County

Federal and state agencies, including the USDA Forest Service, CAL FIRE and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, joined forces with UC Cooperative Extension and quickly mobilized resources to control the pathogen in Redwood Valley and halt its spread to neighboring forests. Local landowners have also played a key role.

Yana Valachovic, UC Cooperative Extension advisor in Humboldt County and forestry expert, explained that she and her agency partners had been preparing for this moment.

“We’ve been closely monitoring the disease for years and anticipating a scenario like Redwood Valley, so we were ready to take action and respond quickly,” Valachovic said.

The UCCE staff leads an extensive sudden oak death monitoring program on the North Coast, and one of their detection strategies involves "leaf-baiting" in streams. Using this technique, they “bait” Phytophthora ramorum, the non-native pathogen that causes sudden oak death, by placing susceptible leaves in strategic locations in North Coast streams. If the leaf baits become infected with SOD, the scientists know that the pathogen is present in the watershed without having to comb the landscape for symptoms.

After they detected the pathogen in Redwood Creek, UCCE acted quickly to pinpoint the source of the waterborne spores, scouring the watershed for the very inconspicuous symptoms of SOD with the help and permission of public and private landowners. By November 2010, the scientists had narrowed the location to Redwood Valley, where they found dead tanoaks and several other infected host plants.

Given its proximity to extensive public, private and tribal lands, the infestation in Redwood Valley was a serious concern. The disease, which was discovered in the Bay Area in the mid-1990s, is found in 14 coastal counties in California, from Monterey to Humboldt, and has infested 10 percent of the at-risk areas in the state. P. ramorum thrives in the coastal climate, and has killed over 5 million tanoaks and true oaks over the past 15 years. It’s still not clear how the pathogen got to Redwood Valley, but it could threaten the dense tanoak forests of the surrounding area, resulting in widespread tree mortality and increased fire hazard.

Much of the on-the-ground effort has been completed by contractors and CAL FIRE handcrews, who have created 100-meter buffers around infected trees by removing California bay laurel (pepperwood) and tanoak, the two hosts that most readily support P. ramorum spore production and spread. Infected plant material has been trucked offsite and donated to the nearby DG Fairhaven Power Company, piled and burned, or lopped and scattered onsite.

Funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the USDA Forest Service and NRCS enabled the swift response in Redwood Valley. UCCE used ARRA funds, also known as federal stimulus funds, to hire four people to work on the project, lending stability to the effort.

Landowner support has been critical to the success of the project, according to Valachovic. More than 20 landowners in the valley have allowed monitoring and treatment activities on their properties, recognizing that their cooperation may keep the disease from spreading to other areas.

“We couldn’t just stand back and let the disease roll through the forests that we manage, and the landowners understood that,” said Dan Cohoon, who works for Eureka-based Able Forestry, which manages many of the private forestlands in the watershed.

Brandon LaPorte, manager of Cookson Ranch and one of the key landowner collaborators in Redwood Valley, has supported the project from the beginning. LaPorte explained, “We’ve learned a lot about the disease through this project, and we certainly don’t want it getting worse here on the ranch or spreading beyond the valley.”

The first phase of treatment is currently wrapping up, and UCCE is beginning to monitor project efficacy and watch for spread of the pathogen beyond project boundaries. The Yurok and Hoopa tribes will be paying close attention to this effort, as they are only a ridge away from the infestation.

Ron Reed, a Yurok tribal forester, commented, “Oaks are an important part of our culture and history, and we will do what we can to keep sudden oak death out of our forests.”

The Redwood Valley project highlights the value of stream monitoring as a detection tool for SOD, but it also demonstrates the ability of agencies and landowners to collaborate swiftly and effectively to protect the region’s forest resources. Maybe most important – regardless of the future course that sudden oak death takes in the North Coast – is what the project shows about the ability of proactive communities concerned about the health of their landscapes to come together, attract the support of state and national authorities, and work to make things better.

The community collaboration is being honored with the Two Chiefs’ Award. The award, which is given jointly by the NRCS and the Forest Service, highlights projects from across the country each year, recognizing exemplary partners who have worked collaboratively to support conservation and forest stewardship. Kathleen Merrigan, USDA deputy secretary, will present the award and Valachovic will accept the award on behalf of the federal, state, tribal and private partners involved the project at an event in Davis on Wednesday, May 16.

For more information about sudden oak death disease, visit the California Oak Mortality Task Force website at www.suddenoakdeath.org.

SOD has killed over 5 million trees in California.